GCSE results: Trends explained

- Published

A massive boost for single-science subjects is offset by a continued decline in French and German, while the gender gap widens slightly - a look at the trends emerging from the 2010 GCSE results.

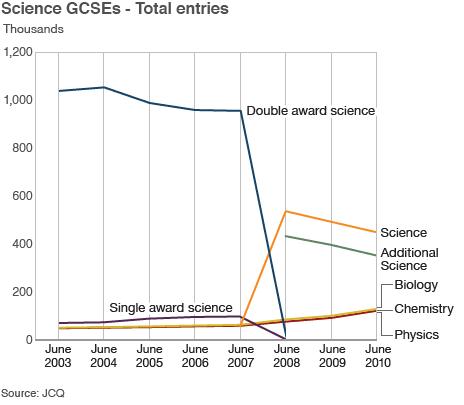

Rise in single sciences

A government drive to resurrect dwindling numbers of entries in chemistry, biology and physics from the late 1990s has yielded massive growth in the past few years.

Numbers have doubled since 2007, but still only 16% of students take triple science.

The push follows concerns that the combined science courses, which squeezed all three subjects into one or two GCSE options, did not prepare students properly for A-level and beyond.

The Labour government set a target that 90% of schools should offer triple science. In early 2010, it was estimated that 70% of state schools offered it - though in 2009 only 32% entered pupils in single-science GCSEs.

Schools describing themselves as having a science specialism have only recently become obliged to offer triple science.

Meanwhile, a wave of competitions and events have attempted to interest pupils.

And the courses themselves have been updated to make them more engaging, challenging and related to current scientific issues in the media such as climate change.

What were previously "double" and "single" award science have been revamped into "science" and "additional science" - with the latter designed to be more academic and challenging.

The Campaign for Science and Engineering says there are still problems, particularly shortages of suitable teachers - 25% of schools do not have a specialist physics teacher, for example.

"The increase is fantastic," said its assistant director, Hilary Leevers, "but the figures have risen because they started in such a low place".

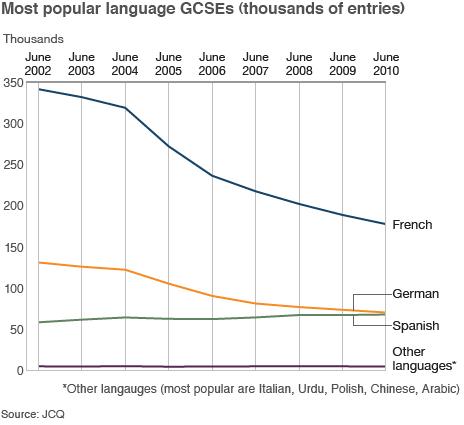

Drop in French and German

The number of students taking French and German this year are both just more than half the number in 1999.

AQA exam board head Andrew Hall said this year's drop of 5.9% had pushed French out of the top 10 subjects "for the first time in living memory".

It continues a steady decline since 2004, when it stopped being compulsory for 14-year-olds to take a language.

Ziggy Liaquat, managing director of the Edexcel exam board, said the decrease in languages was "disappointing".

"There is a conversation to be had about how we do make languages more engaging, more interesting, more relevant for young people," he said.

But John Dunford, head of the Association of School and College Leaders, said pupils were avoiding languages because they are harder than other GCSEs.

"The pressure on young people to pass means they do not want to do harder subjects," he said.

CILT, the national centre for language learning, agreed with this analysis, saying the trend was "less to do with student disaffection" and more to do with "performance table pressures".

It said the system was "letting down" young people by allowing them to opt out of languages.

Spanish has bucked the trend, however, with a slight increase. And there has been a rise over the past decade in students studying a range of other languages spoken in the UK.

It is assumed that the majority of the growing numbers of students taking languages such as Arabic, Chinese, Polish and Urdu have some personal connection to the language - and many will already be fluent in it.

Gender gap

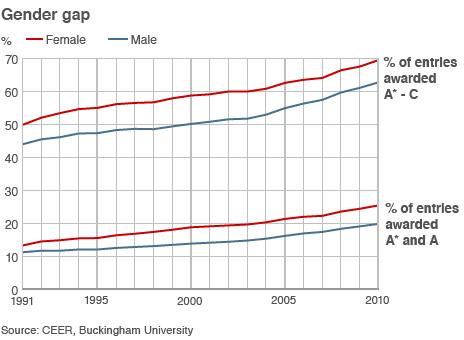

Boys continue to lag behind girls in most subjects, a trend of more than two decades.

The gender gap was at its widest in the early 2000s for A*-Cs, and in the middle of the decade for A*-As.

Explanations for the gap vary, although it is widely thought that girls perform better than boys in continued assessment and coursework. Other reasons given for the gap in GCSE performance are maturity and motivation.

However, a higher percentage of boys get A and A* grades in economics and additional maths than of girls. Boys also pulled ahead of girls at these top grades in maths last year, and in physics at A grade - and managed to maintain the edge in both in 2010.

Nations and regions

Northern Ireland's teenagers consistently bag a higher proportion of top grades than those in England and Wales.

Northern Ireland still has a system of selective schools, where pupils are tested at the age of 11, with the brighter ones going on to grammar schools.

In Wales, however, the percentage of entries gaining A*-C grades has slipped from being higher than in the rest of the UK, to lagging 2.6 percentage points behind.

One suggested reason is a funding gap, with the National Union of Teachers saying £500 less is spent per pupil in Wales than in England.

There is also speculation that more pupils in Wales, where there are no school league tables, may be entered for exams they might not perform well in, in comparison to elsewhere.

Across the UK regions, south-east England and south-west England tend to perform the best at grades A and C, but in the past two years the north-east England and London have shown the most improvement.

Religious studies up, ICT down

Some subjects confound popular perceptions. While many assume the UK is becoming more secular, the number of entries in religious studies has risen for the twelfth year running.

The subject is now in the top ten most popular subjects, with entries increasing more than 60% since 1999.

The Church of England believes "young people are clamouring for a deeper understanding of religious perspectives on issues of the day and how moral and ethical questions are considered by the major faiths".

Exam boards have rejected claims by the Campaign for Real Education that the GCSE is "pathetically easy".

Grades in religious studies are fairly similar to history, ICT, geography - although the percentage of good grades in a subject does not necessarily indicate how hard or easy it is.

One reason for the rise may be that it is compulsory for schools to provide some form of religious studies education for students, so some schools and students may decide that they want the time and effort it takes to count towards a GCSE.

Conversely, the iPod generation has continued to turn its back on information and communications technology (ICT), with the number of entries dropping by nearly a third over the past decade.

Exam boards suggest the drop in the last couple of years may be because, with more students taking triple science, ICT is often abandoned to enable students to keep more breadth in their choices.

But this does not explain the longer-term trend.

The Royal Society has suggested that courses are "poorly conceived" and the way the subject is taught "turns off" pupils.