US students start to question degree costs

- Published

Going to college in the US is a rite of passage

It's a ritual as American as Thanksgiving or the Super Bowl: the latest wave of 'freshmen' arriving on campus in jam-packed SUVs driven by proud parents.

Going to college has been a rite of passage for generations of Americans, more so than the rest of the world where mass higher education is a more recent phenomenon.

In the US, getting into college, especially the right "school" is the key step on the route to career success.

A college degree has been a reliable meal ticket. No-one seriously questions whether it is worth the cost. That is, until now.

Each year, US News & World Report, ranks American universities. This year was no different except that, alongside the consumer guide to campuses, the editorial asked 'Is college still worth it?'

It argued that with tuition fees at many private colleges now exceeding "the once unthinkable $50,000 (£32,000) a year", the US could be at a "tipping point" of consumer change with students and parents starting to doubt whether the investment is worth it.

The magazine says some analysts are predicting that higher education is the "next economic bubble, headed for a crash", and concludes that "if colleges were businesses, they would be ripe for hostile takeovers, complete with cost-cutting and painful reorganisations".

This could be magazine hype, but bookshop shelves heave with new books asking the same question.

They include titles such as Higher Education: How colleges are wasting our money and failing our kids, and The Five Year Party: How colleges have given up on educating your child and what you can do about it.

Frat houses

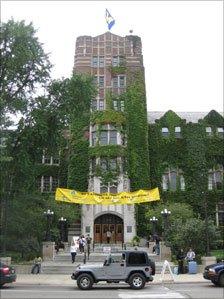

This cynicism was not immediately apparent on the campus of the University of Michigan, one of the country's top public universities, when I visited at the start of term.

Students resplendent in their Michigan sweatshirts and baseball caps (Americans love their college branding) strolled the impressive campus, registering for classes, and signing up for the fraternity and sorority houses.

At the season's opening football game, the Michigan Wolverines ran out in front of an astonishing 113,000 fans at the "Big House", the expensively revamped stadium that is the largest university sports arena in the country.

Getting into the right 'school' is a key step in career success

But here, as elsewhere, tough questions are being asked about lavish spending on facilities and sporting programmes when tuition fees, and class sizes, continue to rise.

The annual cost of tuition plus rent and all other costs for undergraduates at Michigan is estimated by the university to be $25,000 (£16,000) for students from in-state and $50,000 (£32,000) for those from out-of-state (public universities in the US offer much lower fees to local students).

As it takes four years, typically, to graduate that means out-of-state students will spend some $200,000 to gain a degree.

This year Michigan put fees up again by 1.5% for in-state students and 3% for those from out-of-state. However, in a sign that the crunch on fees is approaching, this was the smallest increase since 1984.

A University of Michigan spokesman said this relatively small fee rise coincided with a record $126m investment in centrally awarded financial aid to students and after "trimming recurring costs by a collective $159m over the past seven years".

The university's president, Mary Sue Coleman, has also made plans to cut a further $100m over the next three years, at a time when funding from the state is set to decline.

Bottom-line

Nevertheless, this increase in fees lifted the lid on resentment that exists just below the surface.

Comments on the university's website were overwhelmingly angry that the university was raising fees not cutting costs.

Some questions pending on facilities when tuition fees, and class sizes, continue to rise

Some cited the pay of the university's president (her total salary package exceeds $750,000 - although she asked for a pay freeze in 2009). Others cavilled at the six-figure salaries paid to professors.

Yet more complained that as their fees went up, they received more teaching from graduate assistants than from professors.

The growing cynicism about university finance was reflected in a poll earlier this year for the National Centre for Public Policy and Higher Education, which found that 60% of Americans believed universities cared more about their bottom line than about improving the student experience.

Online enrolments up

The ever-rising cost of tuition fees in the US is a sober warning of what could happen in England if the independent Browne Review, commissioned to advise on the university funding system and due to report in October, lifts the cap on tuition fees and creates a market.

American universities have been hit by a double whammy: endowments are down because of the performance of investments and grants to public universities are being steadily squeezed as the states cut public spending.

The University of Michigan's investment portfolio fell by $1.9bn in 2009 because of the global financial crash. Meanwhile, it is budgeting for a steady decline in state grants.

According to federal government statistics, tuition fees and other undergraduate costs at public universities rose by 32% in the decade to 2008/9.

The average cost of tuition fees plus 'room and board' in 2008/9 was just over $12,000 at public universities and $31,000 at private universities.

However, as yet, there has been no drop in demand from university applicants. The US government predicts enrolments will rise until 2018.

Uncapped fees

However, students are now looking at cheaper options, such as taking at least part of their degree at cheaper, local community colleges (similar to further education colleges).

There has also been a rapid rise in enrolments at online universities, such as the University of Phoenix.

Last year, according to the Sloan Survey of Online Learning, online enrolments rose by 17% in 2008, compared to a rise in traditional enrolments of just 1.2%.

Over 4.6m students are now taking online university courses with one in four students now taking at least one course online.

As the debate over the Browne Review continues, many will point to the success of the US university system as evidence that a market-based system of uncapped fees works.

Yet, while US higher education still leads the world, the strains of the financial burden placed on students are starting to show.

Mike Baker is a freelance writer and broadcaster specialising in education. www.mikebakereducation.co.uk, external

- Published16 September 2010

- Published20 August 2010