Q&A: EMA grants

- Published

Key questions answered over the scrapping in England of Education Maintenance Allowances - support grants for low-income 16 to 19-year-olds in the UK to help them stay in education.

What are EMAs?

Education Maintenance Allowances are payments of up to £30 a week given to students from low-income households in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland if they stay on at school or college. The payments are under review in Northern Ireland.

They are paid either weekly or fortnightly directly into the student's bank account and are not affected by any other benefits the family receives.

Pupils who do not attend class without a good reason do not receive their payments.

Why were they introduced?

Piloted from 1999, and then rolled out UK-wide in 2004, EMAs have been described as "incentives", and even "bribes". They were brought in to boost the numbers of young people from deprived backgrounds staying on in education.

Who receives them?

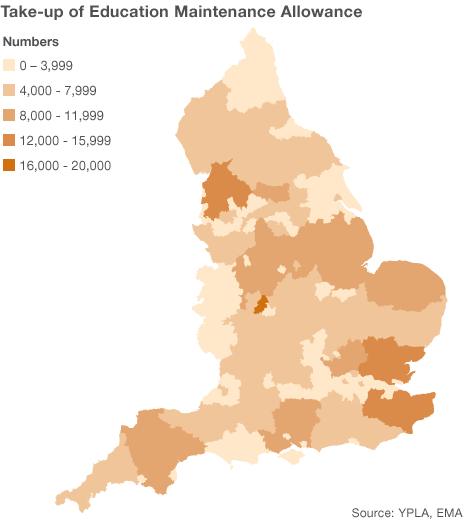

In England, some 650,000 young people are receiving EMA this year - 45% of 16 to 18-year-olds in full-time education.

Students from families earning up to £20,817 receive £30 a week, those with incomes between £20,818 and £25,521 receive £20 a week, while those with household incomes of £25,522 and £30,810 receive £10 a week.

The thresholds are slightly higher in Wales and Northern Ireland and payments are made fortnightly. In Scotland, the £10 and £20 payments have been cut, and the earnings threshold for £30 is slightly lower.

Any money the student earns, for example through a part-time job, is not included in the earnings calculation - nor are child maintenance payments if parents are divorced.

What do students spend EMAs on?

Students use the money to cover the cost of books and other equipment for the course - such as tools or clothing for vocational courses like catering or construction.

The allowance is also widely used to cover transport costs. Local authorities have a statutory duty to ensure that the cost of transport is not a barrier to learning.

But colleges are warning that many students, especially those in rural areas, nevertheless rely on EMA and may suffer as local authorities face funding cuts and may struggle to subsidise transport.

Students are, however, free to spend the money on whatever they like.

What are the arguments for scrapping EMAs?

The government argues that EMA is expensive and wasteful, costing over £560m a year with administration costs amounting to £36m - at a time when ministers are trying to reduce the national deficit.

The Department for Education cites research by the National Foundation for Educational Research saying that 90% of students who receive EMA would still continue with their education without the payment.

Chancellor George Osborne described this as "90% deadweight costs".

What are the arguments against scrapping EMAs?

Opponents of the decision to scrap the EMA say the allowance has worked to keep young people in education.

They point to research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies that says the scheme has raised participation as well as boosting grades.

The IFS says that even if the claim of 90% "deadweight" cost is accurate, the costs of providing the allowance are offset by the financial gains of getting young people into training.

Campaigners say the study that produced the 90% figure was not representative, and also point out that in some colleges EMA recipients have higher rates of course completion than other students.

And anecdotally college principals say it is very effective in keeping attendance levels high.

A National Union of Students poll in 2008 said six in 10 students on EMA would drop out without the allowance.

Will there be any help for poor students now?

In March 2011, the government announced that in England it would replace the scheme, which cost £560m, with a £180m fund for low-income learners.

About £15m of this will be used to give 12,000 of the most disadvantaged 16 to 19 year olds bursaries of £1,200 per year. These are young people who are in care, leaving care and those on income support.

The rest - £165m - will become an expanded version of the existing £26m "learner support fund", given to schools, colleges and other training providers, for them to use at their discretion to help their poorest students with study-related costs.

Schools and colleges will be able to make these payments conditional on attendance and behaviour if they want to.

What about students already receiving EMA?

When the scrapping of EMAs in England was first announced, colleges were told to stop accepting applications for EMA from January 2011. Students already receiving the allowance were told they would continue to do so for the rest of the academic year - but it was not clear what would happen after that.

Campaigners feared about 300,000 students would lose their financial support midway through their courses.

However, in March the government said students who had begun receiving EMA in 2009-10 would continue to receive the same payments until the end of the 2011-12 academic year.

And, it said, those who had started the first year of a course in 2010-11 and were eligible to receive £30 a week would receive £20 a week until the end of 2011-12.

Those who started courses in 2010-11 but receive less than £20 a week may still get help after September 2011, but it will up to their school or college to decide.

How will the £165m funds be divided between England's colleges - will poorer areas get more?

The government is conducting an eight week consultation to decide how best to allocate the money.

What about the rest of the UK?

EMA has already been reduced in Scotland. No plans have been announced to cut it in Wales, but it is under review in Northern Ireland.

Didn't the Conservatives say they would keep EMAs?

Before the election, they said they had no plans to scrap EMAs.

At an event in January 2010, before he became prime minister, David Cameron said: "We don't have any plans to get rid of them..." although he said he had observed that the grants had a "mixed reception" among students he had spoken to.

Scrapping them is "one of those things the Labour Party keep putting out that we are [planning to do], but we're not," Mr Cameron said.

Michael Gove, now Education Secretary, made similar comments to the Guardian newspaper in March 2010.

Isn't the school-leaving age being raised anyway?

Yes - currently in England, education is only compulsory up to the age of 16. This will be raised to 17 in 2013 and 18 in 2015.