Last stand for student EMA grant

- Published

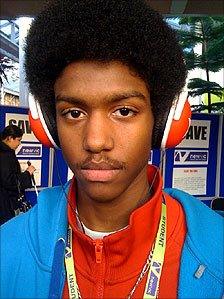

Ali Mohamed says the grants make the difference between staying in school or dropping out

The government is "guilty of thinking that young people are an easy target for cuts," claims Labour's education spokesman Andy Burnham.

Meeting a group of sixth formers in east London, he backed their calls for the education maintenance allowance to be protected.

The government wants to scrap this means-tested payment in England of between £10 and £30 per week to teenagers.

They say it is poorly targeted and expensive to administer - available to almost half of 16 to 18 year olds in education, rather than those who really need it.

At Newham Sixth Form College, ahead of his parliamentary attempt to stop the removal of these grants, Mr Burnham talked to youngsters about their concerns.

In this deprived part of London, 41% of youngsters qualify for the support grant.

'Basic funding'

"This is basic funding - it's used for pens, pencils, travel, text books. If you can't have this, you can't succeed," says Ali Mohamed a student here taking A-levels in business, maths, English literature and law.

This 17 year old has also been elected as the local youth mayor - and he says that people from more affluent areas should not underestimate the significance of these payments for some teenagers.

"It makes a big difference to whether someone can stay on or not," he says.

There's a strong sense among these youngsters of a social divide in how these payments are viewed.

Henrique Costa says some people do not see importance of EMA to students

When they step outside the college they can see the business flights taking off from City Airport - they can see the Docklands Light Railway ferrying commuters into the financial towers of Canary Wharf.

It's a short distance, but a big divide, and these teenagers say that their future is going to depend on their educational opportunities.

"If you don't invest in young people, it's short sighted," says Samuel Berhanu. "It feels like the poor are being judged."

Another student, Henrique Costa, puts it into a local context. He says part-time jobs are getting harder to find for teenagers, he says parents are struggling to get by - and he says ending the EMA will "cause havoc" for families.

"People would drop out," he says.

A payment of £10 per week might not seem a lot to some people, but it could have a far-reaching impact, say these teenagers.

Mr Burnham is playing to a sympathetic crowd with his message that the payments should be protected - and he says that scrapping it is an act of political spite.

In Newham 41% of pupils receive an EMA

"The EMA sent young people a message that education could be for them. To take that away is very worrying.

"The government is isolated on this. It's a mess of their own making. The evidence shows that this scheme has been a success, with the cost completely offset by the benefits. That was why they promised to keep it."

"It seems as though the government is determined to smash to pieces anything from the last government, even it's been shown to work."

'Divisive'

The government rejects such claims, saying it is committed to ensuring that those facing genuine financial barriers will be given the resources they need to stay in education - and that there will be further announcements of such support plans.

Since the idea of the EMA was first tested it has divided opinion.

In this east London college it is seen as a lifeline, a financial bridge during a vital few years which could decide much of a young person's future.

A student at Newham Sixth Form College says that the EMA "gets people out of their beds".

But it raises the question as to whether teenagers should need a financial incentive to turn up at school or college.

And it is another example of whether the social benefits of giving money to the deserving is worth the risk of some of that money going to the undeserving.

Andy Burnham says it's wrong to call EMAs a waste of money

There are certainly different perspectives in different parts of the country.

A secondary school teacher in Lincolnshire, who didn't want to be identified, described the payments as a "well-intentioned farce".

He says that the payments don't seem to go to the most deserving pupils and the money is often misused for items such as car insurance.

"Teachers have lost count of the children from split families or with self-employed parents, usually fathers, who successfully arrange for their children to get EMA by claiming to have very low incomes.

"It is incredibly divisive in classrooms where kids from modestly well-off families with married parents don't get EMA," he writes.

"If EMA is to go and be replaced with something that actually goes to genuinely deserving cases then it couldn't happen more quickly as far as I'm concerned."

With the decision to replace the EMA with a new support system unlikely to be reversed, there will now be attention on how it affects staying-on rates.

And the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, which wants to encourage more apprenticeships, has been angered that the EMA is being cancelled without knowing what is going to take its place.

One of the Newham students seemed unimpressed by the entire political process - saying that whatever was promised, it felt like people like himself were going to lose out.

"It always seems to come around to us," he said with a shrug.