Gove's curriculum: Is less really more?

- Published

Science will remain compulsory - but what about other subjects?

In 1987, the then Conservative Education Secretary, Kenneth Baker, announced on television that England and Wales would, for the first time, have a national curriculum.

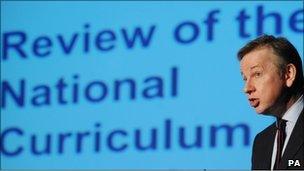

Now, his successor Michael Gove has announced a potentially radical review of that compulsory curriculum.

This review will reduce the overall breadth of the compulsory curriculum but will increase the "essential knowledge" that all pupils must know by the age of 16.

The differences between the approaches then and now are illuminating.

In 1987, Mr Baker (now Lord Baker) said a national curriculum was needed because "we can no longer leave individual teachers, schools or local authorities to devise the curriculum that children should follow".

Today, Mr Gove argues insists that the government wants to give schools greater freedom over the curriculum - although not to the extent that there need be no compulsory curriculum at all.

'Jam-packed'

In 1987, Mr Baker created a 10-subject national curriculum, despite the fact that his Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, wanted just three subjects: maths, English, and science.

Mr Gove has long called for a slimmed down national curriculum

Today, Mr Gove wants at least four compulsory subjects for all pupils from age 5 to 16: maths, English, science and PE.

He is leaving it to an expert panel to advise on how many from a list of eight other subjects should also be compulsory.

However, the introduction of the English Baccalaureate appears to pre-empt a decision to make a foreign language and either history or geography mandatory too.

He has also said Religious Education will remain a statutory requirement.

That would leave it open for citizenship, ICT, design & technology, art and music to be dropped from the current compulsory timetable at all levels, although schools would still be encouraged to teach these subjects in their own ways.

In 1987, the government was wary of taking too much power to the centre, so Parliament required that the curriculum be decided at arms' length from ministers by a new quango, the National Curriculum Council.

Today - in a little-noticed but significant move - Mr Gove has handed control of the curriculum to his own department.

'Overload'

By so doing, he has effectively created England's first nationalised curriculum.

In 1987, Mr Baker wanted the national curriculum to take up to 80 or 85% of the school timetable.

But it was so jam-packed that, according to some experts, it really required 120% of the timetable if it was to be covered properly.

Indeed, Mr Baker told Mr Gove he regretted he had legislated to lengthen the school day.

This overload led to several subsequent revisions of the national curriculum, mainly designed to reduce the content.

But, some advocates of reform say these changes reduced the essential core factual knowledge so much that it left a curriculum that was stronger on general principles than facts.

Indeed, as Mr Gove has highlighted, there is relatively little required factual content in the current curriculum.

In history, for example, only two names of historical characters are cited: Olaudah Equiano and William Wilberforce - and they are only mentioned in explanatory notes on the abolition of slavery.

While it is clearly ridiculous to claim that this means no pupils are taught about, for example, Queen Victoria, Winston Churchill or Henry VIII, it seems an odd omission.

The same is true in geography, where the current curriculum documents name only two specific locations: the UK and the European Union.

Good schools and teachers will, of course, already be covering lots of factual content in both history and geography, but Mr Gove's point is that a national curriculum should set out a minimum core content that pupils should know about their own country and other parts of the world.

But this is where it gets tricky. Mr Gove wants both to reduce prescription but, at the same time, to insist on minimum, specified knowledge.

He says he wants to reassure teachers that there will still be plenty of time outside the compulsory curriculum for schools to teach whatever else they think is right for their pupils.

But when I asked him if he would say just how much of the school week the national curriculum would take up, he would not say.

Mr Gove stressed the importance of England keeping up with its international competitors

His argument is that the review itself should decide, although he did note that his coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, had called for a "minimum curriculum entitlement" filling no more than 50% of the timetable.

However, as the head of the review, Tim Oates, pointed out, it is not sensible to state a percentage limit as some children will need to spend more time on absorbing factual content than others.

But without some reassurance on this, many teachers and parents will fear that the new compulsory curriculum could, albeit unintentionally, squeeze out other subjects such as art, music, drama, media studies, or citizenship.

Mr Gove insists this is not his aim. He has support from several head teachers who agree that, whatever the demands of the new national curriculum, they would defend their pupils' right to a broad and balanced timetable.

But, despite these reassurances, suspicion remains that the national curriculum will constrain schools.

Critics also complain that it is inconsistent for academies and "free schools" to remain exempt from the national curriculum.

After all, the government wants the majority of schools to become academies.

If that happens, some might wonder why the government thinks it important to set out a minimum core of essential knowledge that will apply only to a minority of schools.

Mike Baker, external is a freelance education writer and broadcaster

- Published20 January 2011

- Published20 January 2011

- Published20 January 2011