High-fee universities warned of sanctions

- Published

There are plans to protect poorer students from the controversial tuition fee increases

Universities in England could be stripped of the power to charge tuition fees of more than £6,000 a year if they fail to admit sufficient numbers of students from poorer backgrounds.

And those setting higher fees could face large fines for missing targets.

New government guidance also confirms universities can admit poorer students with lower grades than other candidates if they show potential.

Universities say sanctions would be unfair.

Critics say the government is cutting access to higher education by raising fees.

Annual targets

Fees are due to rise to a maximum of £9,000 per year from 2012, but the government says it wants to ensure this does not put off poorer students from applying to university.

Any institution wanting to charge more than £6,000 per year will have to negotiate an annual access agreement with the Office for Fair Access (Offa).

This will set a target for how many students from state schools or poorer backgrounds it must recruit in future years, and will be reviewed each year initially, rather than every five years at present.

At the moment just over 7% of pupils in England go to private schools (more attend in sixth form) but they make up about half of those at Oxford and Cambridge.

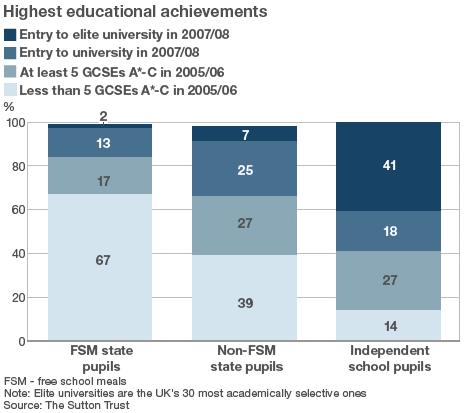

The government says it wants to help pupils on free school meals (FSM) to reach their potential by going to university.

According to a report by the Sutton Trust charity, external, in the 25 most selective universities, only 2% (approximately 1,300 pupils each year) of the student intake was made up of FSM pupils, compared with 72% of other state school pupils. The charity produced a table showing how different universities in England compare.

Offa is to be given the power to revoke the right for universities to charge more than £6,000 a year in tuition fees and to impose a fine of up to £500,000 if the access agreement is broken.

But it has had similar powers (albeit in line with lower fees) since it was set up in 2004 and has never used them.

Details of the new arrangements have been released in a letter from the Universities Minister David Willetts to the director of Offa.

Mr Willetts says the changes will make the system fairer.

"This is a serious set of powers and we think this is a much more effective system than we inherited," he told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4.

His guidance makes it clear universities can admit bright students from poorer homes to courses, even if other candidates have higher grades, because of the potential they show.

This is an explicit endorsement of something many universities already do.

The guidance says admissions tutors might want to look at what is known as "contextual data", including how well a candidate appears to be doing compared with other pupils in his or her school.

The letter says: "This is a valid and appropriate way for institutions to broaden access while maintaining excellence, so long as individuals are considered on their merits, and institutions' procedures are fair, transparent and evidence-based."

It says the government believes "insufficient progress" has been made on increasing access - especially to the "most selective institutions and courses".

Unfair

Dr Wendy Piatt, director general of the Russell Group, which represents some of England's leading universities, said while it was reasonable to expect universities to make every effort to attract poorer students, introducing sanctions would be unreasonable.

"I would be very wary of targets, quotas and fines. It would be unfair to punish universities for a problem elsewhere in the education system," she told Today.

Universities wishing to charge more will also be obliged to participate in - and contribute funding to - the National Scholarship Programme.

In the first year it will provide £50m of support - rising to £150m after three years.

When it is fully running it will assist 48,000 students per year from households with an income of less than £25,000. They will receive funding worth at least £3,000 a year in the form of bursaries, fee waivers or discounts on accommodation.

Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg, who angered students by breaking his pledge to vote against raising tuition fees, said universities who wanted to charge more than £6,000 per year must improve access.

"There is a social crisis in this country - a crisis of opportunity. Universities, the gateway to the professions, are too often acting to inadvertently narrow opportunities, rather than widen them," said Mr Clegg.

But National Union of Students' president Aaron Porter accused Mr Clegg of "living in a fantasy land" if he thought he could become a "champion for students".

"Warm words do not cover the fact that a toothless regulator and a paltry scholarship scheme will do little to offset the impact of vastly reduced investment and trebled tuition fees," he added.

That view was echoed by university lecturers. Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union (UCU) said it was wrong for the government to paint the proposals as "progressive or fair".

In reality it was "tinkering with a failed system" which would cut access to education, she said.

Nick Clegg: "I actually think we will make the university system fairer"

Universities UK said that all universities shared a commitment to broadening access, but there had to be a flexible and autonomous approach for individual universities.

Universities are pleased that targets on admitting poorer students will be put forward by them rather than being imposed.

While the access agreements universities negotiate with Offa will apply pressure to keep fees down - universities argue that they need to raise fees because the government has cut funding.

Oxford University says it needs to charge fees of at least £8,000 to replace university budget cuts.

Pam Tatlow, chief executive of university think-tank Million+, said: "The primary reason why universities may consider charging fees in excess of £6,000 is the 80% reduction in teaching funding which is being implemented following the clear statement in the spending review that the Chancellor expected universities to offset this reduction by charging higher fees."

The 1994 Group, representing research-intensive universities, suggests that it should mean more than a simple headcount of numbers of poorer students being given places.

"Laying down crude targets will do nothing to aid social mobility," said Paul Wellings, chairman of the 1994 Group and vice-chancellor of Lancaster University.

Students protected

There are also tuition fee changes ahead for other parts of the UK.

In Northern Ireland, a report commissioned by the Department of Employment and Learning (DEL) has recommended that fees should rise to a maximum of £5,750.

In Wales, students are protected from increases in tuition fees, with the Welsh Assembly Government subsidising the cost of higher fees.

In Scotland, students do not pay tuition fees.

- Published10 February 2011