London Met University to cut two-thirds of courses

- Published

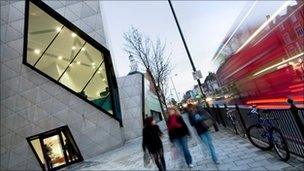

London Met attracts many low-income and ethnic minority students

London Metropolitan University is to cut hundreds of courses, in a bid for financial sustainability in a "much more competitive environment" when fees are increased in England next year.

The university is to "consolidate its portfolio" by dropping from 557 courses to about 160, it said in a statement, external.

A lecturers' union condemned the cuts as unprecedented and unjustifiable.

The university, which takes a high proportion of low-income students, has faced financial problems in the past.

In 2009 it was ordered to repay £36.5m to the Higher Education Funding Council for England in a dispute over the reporting of student numbers.

The university also confirmed that it wants to charge tuition fees ranging from £4,500 to £9,000 from 2012, when the new university funding regime in England comes into effect.

It says its average fee would work out at about £6,850.

In a statement, London Met said that it was announcing a "radical overhaul of undergraduate education".

Many of the courses to be cut had "single-digit enrolments", it said, and as the university reduced the range of subjects it would increase average timetabled teaching time by six weeks each year.

No list has so far been published of the courses to be cut - some are set to close in autumn 2011, and others in subsequent years.

'Difficult times'

Vice-Chancellor Malcolm Gillies told the BBC that there would be redundancies and the total number of staff would be reduced, although there may also be new appointments made to teach new courses.

About 80% of the university's approximately 28,000 students were on just 80 of the most popular courses, he said.

He said his institution was seeking to ensure it could meet future demand in "very difficult economic times".

Government teaching grants to universities are being cut, with the expectation that the money will be replaced by tuition fees paid by students.

Universities Minister David Willetts has said he aims to create more of a market in higher education, including by opening the sector to private providers.

Professor Gillies said universities were "being forced to think of themselves in a business-like way".

"London Met is a university that did have problems a couple of years ago and it takes the issues of a sustainable portfolio very seriously," he said.

"You ultimately have to offer courses that will break even or do better. I think there are many courses here that would not break even. There would be some degrees that are cross-subsidised, but the issue is to what extent do you do that?" he said.

"We're very concerned to make sure we meet demand. The year 2012 is a very insecure one for all universities and we have many private providers entering the market right here in London, particularly in professional subject areas," he said.

He said the university had an obligation to ensure that students already enrolled on courses earmarked for closure could either complete their degree or be transferred to a "parallel course".

This would be achieved through negotiations with groups of students and the individuals concerned, he said.

'Elitist agenda'

Cliff Snaith, the secretary of the University and College Union's London Met branch, said the union "condemns these cuts absolutely", and that the university had chosen a "bargain basement" approach to its fees and courses.

"This is a shrinkage of university provision that's unprecedented and unjustified," he said.

He said the majority of the courses being cut were academic subjects, including history, performing arts, philosophy and modern languages, rather than vocational courses.

"The specific intention is to deprive essentially working class, ethnic minority students of the opportunity to study any non-vocational course," he said.

"This is basically the vice-chancellor... saying that students at London Met do not deserve history. We think this is an elitist agenda to cut working class higher education."

'High risk'

Mr Snaith said London Met's students were seen as high risk for lending, particularly those doing non-vocational courses who had less clear routes into employment after graduation.

"The government does not want to bankroll our type of students," he said.

"UCU and Unison staff will resist all cuts to courses, jobs and provision at London Met by whatever means, including industrial action, unless management reverses direction."

Professor Gillies, who studied music and classics, rejected the assertion that the university was cutting most of its academic courses.

English literature, creative writing, anthropology, sociology and chemistry were among subjects that would still be taught, he said.

"We are offering one of the most affordable portfolios of courses in the land, we seek to challenge that elitism, not to embrace it," he said.