Looking back with the 1968 rebels

- Published

Paris 1968: Future historians will be able to listen to first-hand accounts

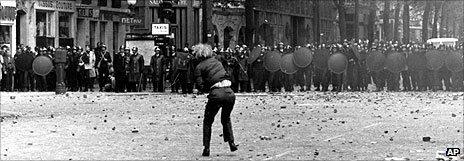

The wave of political protests of 1968, that ran through European cities from Paris to London to Prague, and swept across campuses in the US, remains the most iconic example of student radicalism.

Four decades later, students taking part in the tuition fee demonstrations in London were still invoking the "spirit of 1968".

But this generation, who were synonymous with '60s counter-culturalism, are now in their 60s and beyond.

And an international research project, headed by Prof Robert Gildea from Oxford University's history faculty, has been building a digital archive of first-hand accounts from the demonstrators.

The project - Around 1968: Activists, Networks and Trajectories - has recorded the spoken testimonies of more than 500 protesters from all over Europe.

The database of these recordings is not open to the public. Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Leverhulme Trust, it's intended as an academic resource, allowing future historians to listen to the voices of mid-20th Century radicals.

Going underground

But listening into this collection of stories is like exploring a lost world. Gauloises-voiced pensioners talk about their time as teenage revolutionaries.

In Prague in 1968 there were revolts against the Soviet occupation and communist rule

There are protest singers, such as Dominique Grange, now aged 71, who joined a Maoist group in 1968 and sang in occupied factories and took radical films around villages in south-eastern France. She was imprisoned and spent time "underground".

She talks of meetings with farmers where she sang revolutionary numbers such as Down With The Police State.

In the accounts of these French radicals there are endless ideological divisions and sub-divisions of radical groups, sit-ins and occupations, attempts to link students with striking workers, disputes about crossing the line into political violence.

It's easy to parody the earnestness of all this radicalism.

But what's revealing about this archive is how the personal stories underpin the politics.

Andre Senik, one of the radicals in the Paris protests in May 1968, was the child of Polish Jewish immigrants, who had spent his early years under Nazi occupation.

"Being revolutionary for Jews was a paradoxical and rather aggressive way of becoming part of society instead of having to hide," he said.

"It was a way of settling our accounts with parents who told us not to raise our voices, not to say that we were Jewish, to take care that people didn't think ill of us because we were Jewish."

Now aged 73, his later politics are described as "very anti-communist" and somewhere closer to the neo-conservatives.

Generation gaps

These family backgrounds also show how these French 1960s iconoclasts had been shaped by the disruption of wartime. There were absent fathers in prisoner of war camps, refugee camps and displaced families. The spectre of occupation and who had and who hadn't resisted the Nazis lingered in the background.

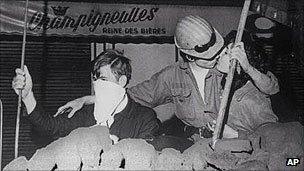

Romance on the barricades: Students near the Gare de Lyon in Paris, May 1968

A radical whose parents had been born in Germany talked of the "abscess" of the Nazi era that remained between post-war children and their parents.

Many of these youngsters had grown up in religious, conservative families, some were privately educated, before being drawn into a period of intense radicalisation. They had stepped from comfortable bourgeois homes into a maelstrom of occupations, strikes and confrontations.

This database also includes accounts of radicals from eastern Europe. In Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, East Germany and the Soviet Union there was opposition to Communist regimes.

In Czechoslovakia this was cultural as well as political, with underground groups such as the Plastic People of the Universe.

Later years

There are also entertaining recollections of how the deep roots of class politics in Britain managed to re-emerge in the guise of left-wing splits.

Sit-ins in London: Students occupied the Hornsey College of Art in May 1968

A contributor describes a political split at a meeting in London about Vietnam - in which one group tried to drown out the other by singing the Internationale.

"What I saw then was a group of public school boys singing the school hymn and a bunch of disaffected grammar school boys basically giving them the V-sign."

But why have the 1968 radicals been influential for so long?

Prof Gildea says they had "wide horizons", sowing the seeds for many campaigning movements that developed in the following decades.

The radicalised youngsters of the 1960s became the environmentalists, feminists, anti-racists and advocates for gay rights of the 1970s and 1980s. It was also a cultural revolution, with the politics interwoven with music, art and writing.

Winners and losers

It was also played out on an international stage before a television audience. The database contains the testimonies of activists from 14 different European countries.

There were also winners and losers among the former radicals. For some it was a case of swapping the barricades for a successful career in the media or campaigning. One of the French activists received an Oscar nomination for a film about 1968.

Meanwhile Prof Gildea says there were others whose lives never recovered from the disruption and who got left behind in dead-end jobs.

There were also others who ended up on the violent fringes, caught up in a cycle of confrontation with the authorities, and who seemed to spend years in and out of prison.

But why should students of the 21st Century still want to draw on the images of the 1960s?

Aaron Porter, who led the National Union of Students through the wave of tuition fee protests, said: "The spirit of 1968 has real resonance with the protests we saw at the end of 2010."

Like their 1968 predecessors, he says students felt they were leading the way for wider opposition groups. And he suggests a shared sense of moral outrage, with students enraged by a more cynical older political generation.

"Students tend to retain a more idealised and optimistic vision of what society can be like. When that vision is brought crashing down it's as though you have been betrayed."

These recordings gathered by Oxford University are going to give future historians a remarkable insight into a tumultuous moment in post-war Europe. It would be like being able to listen to witnesses of the French Revolution.

But what it can't say is whether they were right or wrong.

"As historians, we are here to try to make sense of the routes people went down, not to judge their actions," says Prof Gildea.