'Fake' paintings trick viewers in brain scan test

- Published

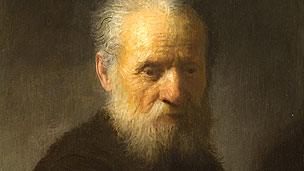

This portrait was established as a Rembrandt last month. Does that make it more enjoyable to look at?

Art lovers looking at a painting they think is fake have an entirely different response from those who think it is genuine, say researchers.

Brain scans revealed how much the enjoyment of art is influenced by the information given to the viewer.

The pleasure revealed in brain activity depended on the viewer believing that a Rembrandt painting was authentic.

Professor Martin Kemp of Oxford University says it shows "the way we view art is not rational".

The pretension-puncturing experiment suggests that the appreciation of art is strongly linked to the accompanying information - rather than an objective judgement.

The pleasure taken from a masterpiece is shaped by the viewer being told by others that this is an authentic work.

Faking it

The study scanned the brains of people as they viewed images of Rembrandt portraits - some authentic and others which were imitations and fakes.

Rembrandt was chosen as a good example because recent scholarship has been trying to identify imitations and copies of the Dutch painter's work.

The experiment in neuroscience and aesthetics compared how the brains reacted to paintings which people thought were authentic with their responses to paintings they were told were fakes.

This found that the responses to viewing an authentic old master were deeply pleasurable, likened to tasting good food or winning a bet.

This warm glow of aesthetic pleasure was absent when the viewers looked at an image they had been told was fake. Instead the brain activity was associated with strategy and planning, as though the subject was trying to work out why this was not an authentic painting.

The study showed the strength of suggestibility in such artistic responses. The beauty was not just in the eye of the holder, but also it seems the copyright holder.

Mapping the brain

Once someone had been told a painting was authentic or fake, their response was shaped by this assumption, regardless of whatever the actual authenticity of the image they were shown.

When a message had been given to a subject that they were looking at a fake, their brain activity reflected their suspicions rather than their pleasure, even if they were looking at an authentic masterpiece.

The measurements were made using a system called "functional magnetic resonance imaging" (FMRI), which maps which parts of the brain are used in a specific mental process.

Professor Kemp, Emeritus Professor of the History of Art at Oxford University, said: 'Our findings support what art historians, critics and the general public have long believed - that it is always better to think we are seeing the genuine article.

"Our study shows that the way we view art is not rational, that even when we cannot distinguish between two works, the knowledge that one was painted by a renowned artist makes us respond to it very differently.

"The fact that people travel to galleries around the world to see an original painting suggests that this conclusion is reasonable," said Professor Kemp.

He says that it shows the extent to which expectation shapes what we experience in art - in the same way that the pleasure of food might be influenced by the description in a menu.

As a follow-up, he says that he would like to try out a similar test on art experts.

As well as Professor Kemp, the study was carried out by Professor Andrew Parker and Mengfei Huang of the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, in collaboration with Dr Holly Bridge at the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB).