University A-level plan challenged

- Published

- comments

A-level courses will need to have much more involvement from universities, under the proposals

Plans to let universities decide the content of A-level courses have been given a mixed reception by teachers and universities.

Education Secretary Michael Gove raised concerns that A-levels were failing to stretch pupils, in a letter to Ofqual, the exam regulator for England.

Ofqual chief Glenys Stacey agreed that more involvement from universities would be "the right thing".

But the ATL teachers' union attacked the plan as a "quick fix gimmick".

The Russell Group of leading universities said they were "certainly willing to give as much time as we can into giving advice to the exam boards".

But Wendy Piatt, the group's director general, cautioned: "We don't actually have much time and resource spare to spend a lot of time in reforming A levels."

The letter from Mr Gove, obtained by BBC Newsnight and sent to Ofqual on Friday, suggests greater control of A-level content should be handed to universities.

"It is important that this rolling back allows universities… to drive the system," he writes.

It repeats a commitment made to head teachers last week that A-levels should be strengthened by the greater involvement of universities.

These proposals, which could be implemented from September 2014, would apply to the English exam system - but exam boards also set A-levels for pupils in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Catch-up classes

The proposal from Mr Gove comes as a study suggested universities wanted A-levels to be more intellectually stretching and with less spoon-feeding from teachers.

Cambridge Assessment, which runs the OCR exam board, found many lecturers believed students arrived unprepared for degree-level work, with three-in-five lecturers saying that their institutions had to run catch-up classes.

Mr Gove's proposal would continue to allow exam boards to design courses, but they would need to show that universities had been involved.

He has asked Ofqual to oversee the new regime: "I will expect the bar to be a high one: university ownership of the exams must be real and committed, not a tick-box exercise."

Mr Gove says the Department for Education should withdraw from developing A-levels.

"It is more important that universities are satisfied that A-levels enable young people to start their undergraduate degrees having gained the right knowledge and skills, than that ministers are able to influence content or methods of assessment," he wrote.

Lack of confidence

"I am particularly keen that universities should be able to determine subject content, and that they should endorse specifications, including details of how the subject should be assessed."

While his letter suggests current A-levels "have much to commend them", he says they "fall short of commanding the level of confidence".

Michael Gove suggests that the primary purpose of A-levels is for university entrance

"Leading university academics tell me that A-levels do not prepare students well enough for the demands of an undergraduate degree," he wrote.

Mrs Stacey said Ofqual has been in talks with the government about the issue for some time.

"Getting universities more involved is the right thing to do for young people," she told BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

"Our job is to make sure qualifications pass muster... we can do it better if you involve universities in the design of A-levels."

But NUT general secretary Christine Blower criticised the plans as another "top-down initiative".

'Disappointed'

"Yet again we see top down initiatives being brought into schools regardless of what the teaching profession may think.

"The NUT is very disappointed that Michael Gove has approached Ofqual without consulting the profession as well."

Mary Bousted, leader of the ATL teachers' union, accused the government of acting on a "whim" rather than on evidence.

"Of course universities have a useful role to play in deciding what should be tested at A level, but A levels need to test more than just the ability to go to university," said Dr Bousted.

There was also caution from the leader of the private school group, the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference.

"Michael Gove is right to want university input into the much-needed review of A levels, but it would be most unwise to give universities total control," said Peter Hamilton, chairman of the group's academic policy committee.

But leading head teacher Anthony Seldon, in charge of Wellington College, warmly welcomed the proposals - and called for a more demanding approach to essay writing.

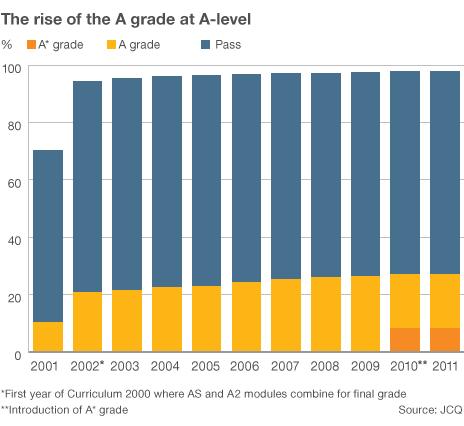

"Much academic rigour and zest has been lost in schools over the past 25 years. Even those with A* grades know remarkably little about physics, geography or history, for example," he said.

The Million+ group of universities accused education ministers of "ignoring advice" from higher education and said changes to A-levels were a "much more complex task than simply getting a few academics together".

And the 1994 Group challenged suggestions that it should be the Russell Group universities which were involved - saying influence should not be restricted to an "arbitrarily selected cadre".

Newsnight political editor Allegra Stratton said that Mr Gove believed: "Standards have to go up if Britain's future workforce is going to have the skills it needs to compete in the future.

"This will mean an era of grade deflation, fewer students will get the top marks."

- Published3 April 2012

- Published3 April 2012

- Published18 August 2011

- Published23 July 2010

- Published4 July 2010