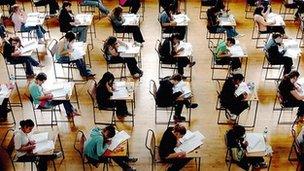

UK schools 'most socially segregated'

- Published

The OECD highlights a growing economic divide between those who succeed and fail in education

Schools in the UK are among the most socially segregated in the developed world, according to a major annual international education report.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report warns disadvantaged children are too often concentrated together in schools.

This applies both to the children of poorly educated parents and to those of immigrant families.

The OECD's Andreas Schleicher says this is the "biggest challenge" for schools.

The Education at a Glance report from the OECD is the leading publication of international education statistics - comparing the performance of education systems among developed countries.

Growing divide

These latest figures, which are from 2010, reveal the UK has unusually high levels of "segregation" in terms of poorer and migrant families being clustered in the same schools, rather than being spread across different schools.

It looks at where the children of "low-educated" mothers are going to school - which in the UK means the children of mothers who did not achieve five good GCSEs - and found that in the UK they were much more likely to be taught in schools with high numbers of disadvantaged children.

Among the children of immigrant families in the UK, 80% were taught in schools with high concentrations of other immigrant or disadvantaged pupils - the highest proportion in the developed world.

The significance of this, according to Mr Schleicher, is that the social background of a school's intake exerts a strong influence on the likely outcomes for pupils.

But the report showed the UK was proving a success in harnessing education for social mobility - particularly in getting young people into higher education.

The chances of poorer children in the UK getting into university are "relatively high", in comparison with other developed countries.

It highlights the progress between generations - with 41% of 25 to 34-year-olds in the UK achieving a higher level of education than their parents - above the OECD average.

The international statistics showed that in some countries social mobility could also go in reverse. In the US, almost one in five young adults faced "downward mobility" - such as not going to university when their parents had.

Degree premium

The figures for the UK are part of a bigger international picture of a growing divide between the educational haves and have-nots.

Despite a growing number of graduates, Mr Schleicher said there was no evidence of a loss of economic advantage from having a degree.

Graduates continue to earn more and remain much more resilient to economic downturns - and those who are less well qualified are growing increasingly vulnerable to lower pay and unemployment.

Mr Schleicher commended the UK's successful efforts to get more young people into university - which he said brought benefits both to the individual student and the wider economy.

He said the latest figures, up to 2010, also suggested tuition fees were not a barrier to higher education - as long as there was an effective system of loans.

The UK system of repaying loans when graduates entered the workforce was hailed by Mr Schleicher as the "most advanced system in the OECD" - and that "probably no system does it better".

But as more young people than ever before get into university, there are others who remain stuck at the other end of the ladder.

In the UK, the report highlights a deep residual problem of the proportion of young people not in education, employment or training, which is well above the OECD average.

"Social disparity is easy to open, but very hard to close," said Mr Schleicher.

Universities Minister David Willetts said: "This latest report from the OECD's confirms that UK universities deliver good returns for students, taxpayers and the wider economy. The earnings premium enjoyed by graduates remains higher than the OECD average and the demand for UK graduates in the workplace continues to be strong despite the global recession. And, very importantly, the numbers going to university from disadvantaged backgrounds continues to rise."

A spokeswoman for the Department for Education, responsible for education in England, said: "The government is determined to put an end to the inequalities of our education system.

"We are targeting more funding than ever before towards the poorest children to help close the appalling attainment gap that has been a feature of our education system for too long. As the OECD states, our Pupil Premium is designed to help schools do this."