Warning over lack of science practical lessons

- Published

Ofsted says opportunities for "illustrative and investigative" scientific enquiry were limited

A lack of practical lessons in schools in England means many teenagers are struggling with science, Ofsted warns.

Inspectors from the watchdog said while many teenagers gained science GCSEs, they did not have the practical skills required to continue studying science.

They also said primary schools were not setting targets for science as they did not see the subject as a priority.

The Department for Education said Ofsted was right to stress the importance of quality practical work.

The report, based on visits to 180 schools - 89 secondaries and 91 primaries - in England, found most science teachers wanted to do experiments in class to spark pupils' interest, but thought this was difficult to do in practice.

"Time in the laboratory was the most pressing concern," Ofsted said.

Inspectors said some secondary schools attempted to teach a triple science GCSE in less than a fifth of a week's school timetable, which meant the only practical work students did was the "necessary minimum" to complete controlled assessments - a form of coursework.

"As a result, opportunities for illustrative and investigative scientific enquiry were limited, and so was the achievement of students," the report said.

'Uninspiring teaching'

The report said "uninspiring teaching" was one of the reasons both girls and boys gave as to why they did not want to continue studying science, while others said they did not see the point of what they were studying.

"Getting the grade is not the same as 'getting' the science," inspectors said.

"Too frequently, GCSE grades indicated that students were doing well but they were not enjoying science.

"Because the subject is a statutory requirement to 16 in local authority maintained schools, and is made compulsory by the academies visited, most students have no choice but to continue studying science at Key Stage 4, and most want to do their best.

"But once they can choose other courses at 16, most students drop science completely.

"Despite some 316,000 students nationally achieving two or more good GCSE grades in science in 2010, only 80,000 went on to study one or more advanced level sciences in 2012. This represents a major loss of science talent."

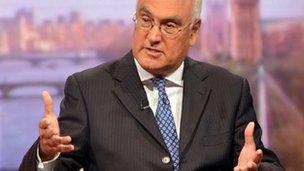

Sir Michael: Leaders and teachers must raise expectations

Inspectors also said too few girls studied physics after the age of 16 and too many dropped it at the age of 17.

The report - Maintaining Curiosity: a survey into science education in schools - says schools must make sure there is enough time for science lessons and enough laboratory space so that pupils can do scientific experiments.

Schools must challenge assumptions about gender and science more and should monitor the future academic and career paths of pupils who continue with science, it says.

Ofsted says the government should ensure science qualifications include an assessment of the skills needed to undertake scientific enquiry.

'Not enough'

Chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw said: "Our inspectors found that many pupils across the country are benefiting from highly skilled and well-informed teaching which stretches and inspires them. But there is not enough.

"We also found that far too few girls study physics, which deprives them of opportunities and leaves the country with a diminished talent pool.

"If leaders and teachers raise expectations, better outcomes in science will follow."

A DfE spokesman said: "Ofsted is right - pupils must learn through high-quality practical work if we are to produce the brilliant scientists vital for our economic prosperity.

"There will be a renewed focus on science in primary and secondary schools thanks to our rigorous new curriculum, which has a far stronger emphasis on practical work. We are also strengthening practical elements in our new science GCSEs.

"Our EBacc [English Baccalaureate] is encouraging more pupils to take physics, chemistry and biology GCSEs, and that is feeding through to A-level - where the number of girls taking the three sciences is at its highest level for at least 14 years.

"We have also raised the level of bursaries and scholarships available to the brightest graduates so they are attracted to science teaching, and can bring the subject to life and inspire pupils."

- Published18 October 2013

- Published5 July 2013