Female genital mutilation: A family speaks out against the abuse

- Published

Three generations of one Somali family speak out about the practice of FGM

As the government announces hospitals are being told to log information on patients who have suffered or are at risk of suffering female genital mutilation (FGM), three generations of one family scarred by the practice have spoken out.

In a modest house in north London, a Somali family debates the wrongs of FGM.

Two of them, grandmother Fatima Ali and her daughter Lul Musse, were cut as girls in Somalia. One, Lul's daughter Samira Hashi, who came to the UK as an infant, has not been and will not be.

Fatima, who is in her 80s, was mutilated in the most brutal way - FGM in its most extreme form, and without anaesthetic.

"I was seven years old," she says, speaking through her granddaughter as an interpreter.

She says she was in a group of four girls and that she initially felt brave and excited and had wanted to go first.

"The woman that was cutting me had my blood, splashing over her face," she says.

She says the pain she went through "nearly killed me" but that she went on to have it done to her daughter because she was "not educated enough" and thought it was the Islamic thing to do.

"I understand now it was wrong and can't let my grandchildren go through what I've been through," she says.

Fatima and her daughter are now vocally anti-FGM. But the most outspoken is Samira, who has become a public campaigner against the practice. She's a student, has worked as a model, and she took part in a BBC Three documentary that took her back to Somalia, where she saw first-hand the effect on little girls of FGM.

"A lot of people are suffering in silence, that's what I learned when I went back home. It's basic human rights. It should not happen," she says.

"It's not just in Somalia. It's embedded in a lot of cultures."

'Child abuse'

Comfort Momoh, who runs the African Women's Health Centre in Guy's Hospital in London, agrees.

Hundreds of women from Africa, Asia and the Middle East have come to the centre for help and treatment after having their sex organs mutilated in childhood.

"It is child abuse. We need to educate ourselves, we need to end FGM and we need to empower the community," she says.

"The community see it as an act of love, as preparing their girls for adulthood. They see it as a rite of passage in some communities... and some truly believe it's a religious obligation, which it's not.

"What I'd like to point out here is that sometimes people tend to think, 'Oh well, it's mainly the Muslim that performs FGM'. The Christian performs FGM alike. It's not in the Koran... not in the Bible, so sometimes people tend to think it's a religious obligation, but it's not."

Hidden

Cutting a girl's genitals is a practice unthinkable to the majority of people. But in the UK it is carried out in communities originally from Somalia, Ghana, Sierra Leone and Egypt, to name a few.

The girls, usually before their 10th birthday, are taken to their countries of origin during the school holidays to have either part or all of their external genitals removed, sometimes without anaesthetic. The trauma is huge, the risk of haemorrhage and infection very high.

It is a secret, hidden business, seen by those who adhere to it as a rite of passage, by those who oppose it as a means of oppression, and by lawmakers as illegal.

Comfort believes FGM is a big problem in the UK

FGM has been a criminal offence in the UK since 1985.

But to date, no-one in Britain has been prosecuted for it, despite reports that it is on the rise.

Part of the problem is getting girls or young women to give evidence against their parents.

There is also a lack of real knowledge about how prevalent it is and where it is taking place - and this is hampering social services and the police in the collection of evidence.

On the United Nations' Day of Zero Tolerance to FGM, on Thursday, ministers are taking a step towards trying to uncover the full scale of the problem in Britain, setting up an official data log, to enable doctors and nurses to record details of the wounds of each victim they see on their hospital database.

This will lead, in the autumn, to the first snapshot of how many women have been treated by the NHS for FGM, and in the longer term will help identify families where the girls are at risk.

Ms Momoh sees women who experience huge physical difficulty and pain in childbirth after being cut. And she sees up to two patients a week who want the operation reversed.

"FGM is a big problem. It is a growing problem, unfortunately," she says.

Turning a blind eye

Official figures put the number of victims of FGM in the UK at about 66,000, but this number is extrapolated from the 2001 census and is widely accepted as being far short of the real picture.

Police and prosecutors have spoken in recent months of bringing the first case to court "imminently", but that has yet to happen. It's in striking contrast to France where 35 cases have reached the higher courts.

Some accuse the authorities in the UK, in the NHS, schools, and social services, of turning a blind eye because of cultural sensitivities - being unwilling to meddle in someone else's accepted ritual, instead of seeing it as an assault inflicted on a child powerless to object.

Ms Momoh says this is right "to some extent," but the big problem is a "lack of knowledge, lack of awareness among professionals".

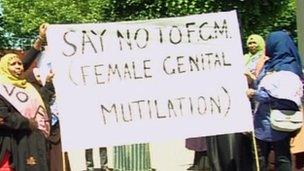

In 2010 women demonstrated in Bristol against genital mutilation

"GPs are the front-line provider or first point of call. If they have lack of knowledge around FGM, what is going to provide the support to women and girls?"

Campaigners want it to be mandatory for healthcare and other professionals to have to report suspected FGM, just as they report stab wounds, or other forms of child abuse.

But although not as bold, they welcome this initiative on data collection in the NHS.

Educating people out of mutilating their girls is the eventual goal and educating the medics who care for the victims is a welcome first step.

- Published6 February 2014

- Published23 July 2013

- Published22 July 2013

- Published19 June 2013

- Published13 June 2013

- Published24 April 2013