How did London become an education superpower?

- Published

Graduate economy: 60% of London's working-age population has a degree

Inner city schools, high levels of deprivation, not speaking English as a first language, a large majority of pupils from ethnic minorities...

And what do you get? The most successful school system in the country.

The city state of London has become an education superpower.

The latest evidence comes from some remarkable statistics tracking pupils' progress after leaving school.

They overturn the conventional wisdom that poorer pupils are doomed to do less well than their richer counterparts.

Among those taking A-levels, 63% of inner London pupils eligible for free school meals continue into higher education.

It's a higher figure than for better-off pupils in the rest of the country. In simple terms, deprived teenagers in inner London are overtaking more affluent youths outside London.

Take a step back and think what it means. Teenagers on free school meals in Haringey and Lewisham are more likely to go to university than better off youngsters in Hampshire or East Sussex.

Stellar results

But what is driving London's spectacular success?

It's become a subject of growing fascination for researchers, looking for the mystery ingredients.

Teach First's Sam Freedman says in his blog that it is "perhaps the biggest question in education policy, external".

There were two reports last week trying to unravel the puzzle, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the CfBT Education Trust, with the capital's progress described as being of "international significance".

Among the theories for London's stellar results:

• make better use of data tracking pupil performance

• rapid intervention to tackle underperformance

• more academies

• better support from councils

• the London Challenge project to support schools

• Teach First, which recruits top graduates into challenging schools

• primary literacy and numeracy strategies feeding through the system

• migrant families ambitious for their children to succeed

Graduate economy

But how about throwing some other external factors into the mix?

London, unlike anywhere else in the country, is a graduate economy. According to the Office for National Statistics, 60% of the working-age population in inner London has a degree.

Abbey Road: London's schools are now chart-toppers

Whether it's a workplace for a barrister or a barista, there are going to be graduates. And it means that a disproportionate number of children in London's schools are going to have graduate parents - even if they are not particularly affluent.

This must have a positive impact on the support available to children at home.

In terms of the diversity of the population, it is the most global city imaginable. More than 80% of children in inner London primary schools are from ethnic minorities, more than half do not speak English as a first language.

In Brent, more than 94% of secondary pupils are not in the "white British" category - and 74% of pupils taking A-levels went on to higher education.

It can't be clear yet how this mobile, ambitious, multicultural population will fit into any traditional models of class. The rigid tramlines of social expectation - depressingly linked to success or failure in education - might no longer apply.

A senior education figure, reluctant to speak on this publicly, says that in terms of driving improvements, the most dynamic combination comes when you have a migrant group which is materially poor, but which places a high status on education. For these families, getting the most from education is their children's passport to a better life.

It's the white working class, a small minority now in inner London, who still seem to remain the outsiders of the education system.

Mobile parents

London schools also serve a very well informed population, no one is more than a few clicks on their mobile phone away from a lot of comparisons about schools. Parents are making some sharp consumer decisions.

Of course this school information is available outside London - and families across the country will be weighing up their best choices.

But what is different is the sheer density of options for parents in the capital. Buses are free for schoolchildren - another practical difference - and that puts a lot of different schools in reach. For these teenagers, the world can be their Oystercard.

Even when the most sought-after schools are oversubscribed and unobtainable for parents - it still provides a local reminder of what should be available.

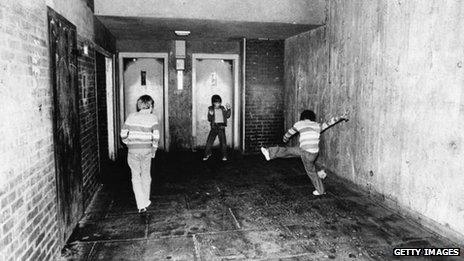

Different worlds: Football kick-around in Bow in east London in 1978

This must apply upward pressure on the system. Heads are under intense scrutiny to get good results. And London schools have become very skilled at maximising their exam grades. The dark arts of data-driven education must be another part of the story.

According to London Councils, in the first decade of the century the proportion of London pupils achieving five good GCSEs rose from 45% to 81%. It's a massive jump - and assuming pupils didn't suddenly all become much cleverer - it shows how much schools have improved in getting the best possible results for their pupils.

Another distinctive feature of London schools is that they come in so many different varieties. There is no "typical" school. There are parts of the capital with a high number of academies and others where local authority schools predominate. There are more faith schools in London than anywhere else. Free schools are adding to the mix. And the sheer cheek-by-jowl nature of the city puts many different types of school in reach.

All these varieties will have their supporters and detractors, but it would be hard to argue in favour of a take-what-you're-given system as an alternative.

Of course nothing is perfect. The rapid rise in population is going to put increasing strain on the system. It's no use having great schools if they don't have a place for your children.

But it must be seen as that rarest of things, a really optimistic education story.