UK shifts to graduate economy, but worry over skills gap

- Published

Record numbers of people will be entering university this autumn

The UK has passed a significant milestone towards becoming a graduate economy, with more people now likely to have a degree than to have only reached school-level qualifications.

The OECD's annual international report highlights an "historic high" in the number of female graduates in the UK.

But the report warns that despite the UK's surge in student numbers this is not matched by a rise in basic skills.

High levels of literacy are more likely in Finland, Sweden and Japan.

The OECD's annual Education at a Glance report reveals the "balance has shifted" towards a graduate workforce in the qualifications of the UK's adult population.

Graduate workforce

There are 41% of working-age people with a degree-level qualification, up from 26% in 2000. This has been driven by rising numbers of young people, particularly women, taking up university places.

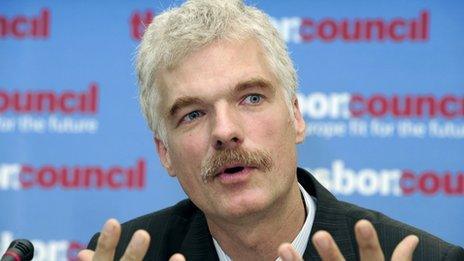

The OECD's Andreas Schleicher said higher education remained good value

This has overtaken the 37% of people whose highest qualifications are school exams such as GCSEs or A-levels.

There are a further 22% who have not achieved a basic level of school qualifications.

It means the UK has the highest proportion of adults with graduate-level qualifications in the European Union and is only surpassed by a handful of countries including South Korea and Japan.

But the report highlights a disparity between the rising graduate numbers and weaknesses in core skills such as reading and writing.

"On the one hand in the UK you can say qualification levels have risen enormously, lots more people are getting tertiary qualifications, university degrees, but actually not all of that is visible in better skills," said Andreas Schleicher, the OECD's director of education.

"Quality and degrees do not always align."

'Variability'

A quarter of UK graduates achieved the top level of literacy in tests, compared with over a third in Sweden, the Netherlands, Japan and Finland. But UK graduates were ahead of their counterparts in France and the United States.

Mr Schleicher said there was "a lot of variability in the skills" of these UK graduates, with some not significantly better than school leavers.

But Mr Schleicher strongly endorsed the value of widening access to higher education, which he said brought advantages to both individuals and the wider economy.

Across the industrialised world, he said graduates were much less likely to be unemployed and likely to have higher earnings.

The "haves" and "have nots" in the economy were now strongly linked to levels of education.

This meant that access to higher education was an important ingredient in promoting social mobility.

Mr Schleicher praised the student loan system for tuition fees used in England, which he said was "one of the few countries to have figured out a sustainable approach to higher education finance".

The report analyses figures from the fees system before the increase to £9,000 fees, but Mr Schleicher predicted this would remain a successful model for student and taxpayer.

But he also argued there was no simplistic link between the cost of university courses and open access.

In Germany, where there were universities without any tuition fees, there was still a problem in a lack of social mobility in higher education.

Mr Schleicher also warned of the United States as a cautionary tale where the university system, once a world leader, had become very expensive and inefficient, overtaken in graduate numbers by many other countries.

The report showed that the US has an unusually high number of young people who are less well educated than their parents, in a form of educational downward mobility.

"The biggest threat to inclusive growth is the risk that social mobility could grind to a halt," said Mr Schleicher.

"Increasing access to education for everyone and continuing to improve people's skills will be essential to long-term prosperity and a more cohesive society."

For the UK, the OECD said public spending on education had been maintained at high levels despite the financial crisis.

Between 2008 and 2011, spending on education, as a proportion of GDP, increased more rapidly in the UK than in any other OECD country.

Anna Vignoles, professor of education at the University of Cambridge, said the increasing number of graduates reflected the sustained advantages in earnings.

"This is particularly so for women. Graduate skills are very much in demand in the labour market."

John Jerrim from the Institute of Education, University of London, said: "The OECD analysis brings into sharp focus the low pay of young people who leave school at 16 with minimal qualifications."

Mary Stuart, vice chancellor of the University of Lincoln, said access to higher education was "not just about equity, important as that is, but also about our ability to compete in a dynamic and fast changing world".

Education Secretary Nicky Morgan said: "This report provides further confirmation that when it comes to our children's education we cannot afford to stand still."