How can education's rich-poor gap be closed?

- Published

How do we open up opportunity for England's poorer children, in particular? Alan Milburn, the social mobility commissioner, has released a report on the topic, external.

One policy comes up quite often: just last week, the Conservatives announced a new set of measures related to school turnaround.

That is to say, the aggressive processes used to take schools that have got bad results and turn them into good schools.

The usual route for this is the so-called "sponsor academy programme".

That programme puts private groups - via charities forbidden from profiting from the schools - in charge of them.

Benefit claims

The first round of them did raise standards at some appalling schools.

But it is worth pondering how much difference improving bad schools can make to the rich-poor gap.

It is widely known that poor children are more likely to go to weaker schools because our school system is socially segregated, so poorer children do benefit more from turnaround.

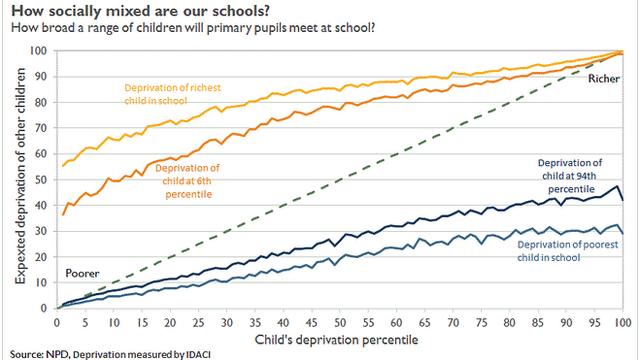

Take children from the very poorest 1% of England's neighbourhoods - that means the areas with the highest levels of benefit claims.

On average, the richest children from the same year at the same state school as those children will come from neighbourhoods in the 55th percentile - just a shade more advantaged than the average.

Significant segregation

To take this a bit further, you can look at the 6th percentile line. You would roughly expect two of the children in a class of 30 above that line.

When you look at that, you find the country's poorest pupils would expect 28 of their 30 classmates to come from roughly the poorest third of neighbourhoods.

That is quite significant social segregation.

To help visualise it, here is a graph showing the same thing for every child.

For example, take a child from the middle of the pile - 50% along the horizontal axis - you can see they would expect to meet no children from roughly the poorest 20% of households or top 15%.

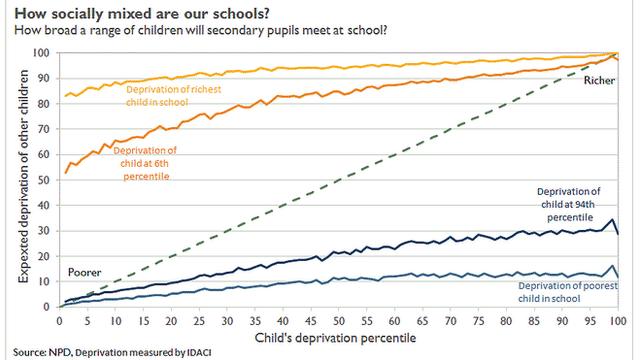

The situation for secondary schools is much less stark; secondaries are fewer in number, larger in size and so recruit much more widely.

The poorest should not expect to meet the very richest at school, but they do at least get a better spread. Every child can expect to meet children from the top and bottom 15%.

That means turnaround is a much more effective policy for closing the rich-poor gap at primary level than at secondary level because the schools are so much more likely to be all-poor.

If you had a lever that would successfully turn around the bottom 8% of schools, the effect on children in the poorest quarter of neighbourhoods would be 50% bigger from the primary school programme than for the secondaries.

But, given the massive scale of the programme, the movement is not very much for either.

Points score

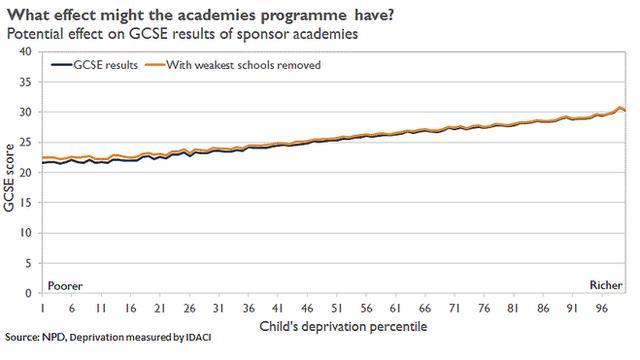

The blue line on the graph below shows GCSE results of children from different backgrounds in English, maths and their three best other subjects expressed as a point score - they get eight points for each A* down to one point for a G.

You can see that poor children, at left, tend to do much worse than richer children, at right.

And the state of the system after that massive, instant turnaround? That's the orange line. Not great.

The problem is not that poor children are housed in the relatively small number of very bad schools - it is that they are less likely to go to good schools, in general.

So a focus on the very weakest does not do much. Segregation is also not the biggest problem.

Social segregation of poorer children into weaker schools accounts for about two of the eight points difference between the richest and poorest 10% of state-educated pupils.

The rest of the gap is caused by the fact that poorer kids do worse than their peers even when they go to good schools.

As-Cs

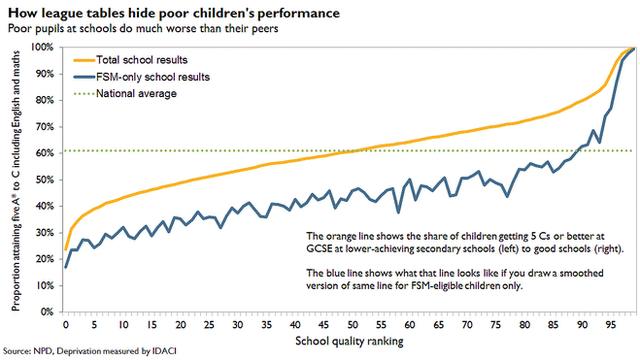

Here is a graph which lays that bare.

To make it, I've divided up schools into 100 categories, from those getting the weakest results (at left) to the strongest (at right) on the government's rather crude measure of school performance - how many get five Cs at GCSE.

You can see the proportion of pupils getting five Cs or better - the orange line - rises smoothly as we go from left to right, from lower to higher performing schools.

Then, just below, I've drawn the same line for the same schools in blue. But, this time, it is for poor children only - those eligible for free school meals. You can see how poor children lag everywhere.

To close the rich-poor gap, turnaround would help. So would measures to make schools less segregated.

But as Mr Milburn's report says, you would still need to focus your attention on all schools. Only a quarter of the gap is segregation.

Even in the very strongest schools, those praised by recent education secretaries for their gap-closing, the gap between rich and poor is three to four points - that is roughly the size of the gap between the children that exists when they turn up aged 11.

The coalition has introduced new league table measures intended to focus their attention on their poorest students. It's the right idea, but it remains to be seen whether they will work.

- Published6 October 2014