How strong is schools' 'London effect'?

- Published

Maybe London's school results are not as good as we have thought? That is the conclusion of the latest report on London schools. This time, it is from Simon Burgess, the director of the Centre for Market and Public Organisation at Bristol University.

The issue is not that London schools do not get good results - they really do. It remains remarkable that no-one had really noticed this until a few years ago. London pupils do astonishingly well.

But maybe the capital's schools aren't the reason why. Maybe it's the pupils. Prof Burgess's striking conclusion is that London's success can be explained solely by the ethnic background of the pupils.

He suggests: "Creating and managing a successful and reasonably integrated multi-ethnic school system is an incredible achievement... If we are to celebrate anything about London's school system, it should be this."

White British children tend to do worse than children from all other major ethnic groups in England - and London has relatively few of them. Once you take account of that, his analysis suggests that London schools do no better than the country at large.

Exam choice

That seems to cut across other reports - including some by me. So where has this come from? It is similar to the reasons why the Institute for Fiscal Studies were also more sceptical about London secondaries than others. It's about exam choice.

Prof Burgess has come to this conclusion because he, unlike me, examined the full range of school qualifications. He is quite right that this is a reasonable way to measure the school system, given that schools were allowed to choose all of those qualifications.

But vocational qualifications create a particular problem. There is a strong consensus that, in historic official weightings, schools have got too much credit for doing vocational qualifications. That is, sadly, why some schools used them - as a cheap way to shoot up the league tables.

League table changes are now forcing a lot of schools to drop their vocational qualifications - and it is showing some schools did not do so well. In Norfolk, Ormiston Victory Academy has admitted its results have crashed from 73% of children getting the equivalent of 5 Cs or better at GCSE (including English and maths) to 43% in a single year, external.

London schools, for a variety of reasons, did less of this gaming than schools elsewhere - about a third fewer per student. They took a more traditional curriculum, so it is difficult to compare London schools to those elsewhere.

Comparisons

In the past, I've dealt with this "exchange rate" problem by excluding all vocational qualifications and, instead, focusing on a narrow basket of GCSEs: English, maths and the three best GCSEs. I do not discriminate by subject choice, but it has to be a full-size GCSE to get credit.

Schools who chose to use a lot of BTecs, say, do not get penalised on this measure so long as they also do a bare minimum of five GCSEs. It is imperfect, since schools obeying the rules might have put a lot of energy into them. But it allows like-for-like comparisons.

In any case, while the measure is "narrow" (it tests few qualifications), it tests schools on precisely the results that universities look at. And whether or not a child actually wants to go to university, schools should not close that possibility off when pupils pick GCSEs at 14.

When you do all of that, you do find a strong London effect.

Prof Burgess finds that too - although his estimate is that there is less of it left than others have found. He also finds that London pupils are much more likely to get very high GCSE grades. So - after at least four reports in the past few months - what do we now know?

There is a London Effect which takes the form of better GCSEs. But - depending on your maths - it is much stronger (or, as per today's research, may even only exist) when you use GCSE grades. It is also not just about pushing pupils to get Ds, not Cs. It is at the top end

The capital's results at 16 are driven by strong primaries as well as secondaries - that was a striking result from the IFS research. And I keep pointing out that London schools are strong in areas that saw lots of high-profile reform energy as well as areas that had none

The role we should ascribe to the "London Challenge" - a big multipart intervention in the capital's schools - seems to be getting a bit smaller with each report. In large part because the contribution of London schools looks a little less exceptional with each report

There is huge ethnic composition to the London story, but the London "optimists" find that London's schools do well by all their pupils

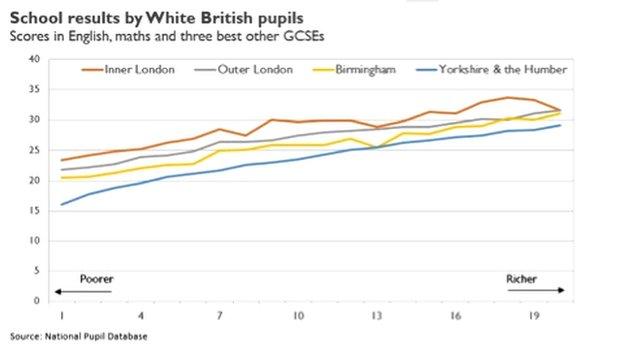

For example, this graph shows how white British pupils do in a number of English regions using a GCSE-only points measure. For reference, all the other regions' lines are stuck together in a lump between the line for Birmingham (drawn in for comparison) and Yorkshire and the Humber.

Poorer pupils are at left and richer ones at the right.

It is quite possible that this is, in effect, a spillover from simply sitting in the same classes as immigrant children. That, itself, might be the root of the "London Effect" - although, at first glance, the patterns you would expect from that do not materialise.

Reasonable people can also differ as to whether I've been fair in simply ignoring lots of qualifications.

But some of the uncertainty around that question will disappear as the league table reforms will force other regions to do a lot more traditional qualifications. We will also get our first sight of that in the detailed 2014 results, which come in the coming months.

As schools' choices of exams become more alike, different subject choices will matter less. If other regions - like the Ormiston Victory Academy - slip back as they move into harder exams, the extent to which London is doing better, and the extent to which it just has better pupils, will be easier to measure.

- Published12 November 2014