Tuition fees: Should they go higher or lower?

- Published

Freie Universitat Berlin: Germany has abolished tution fees for university students

Tuition fees in England's universities are approaching a crossroads. Should they go up or should they go down?

Students are still campaigning to scrap them - saying that putting students into debt isn't the way to fund a higher education system.

And Labour has been flirting with cutting fees to £6,000, without making any firm commitments.

Meanwhile universities have been privately warning against lowering fees unless there is a clear plan for replacing the lost income.

There are also some universities unsubtly pushing to charge more than the £9,000 upper limit.

Either way the fees can't stay frozen forever. A report from the Higher Education Commission this week said the real-terms value of the £9,000 announced four years ago has now been eroded to about £8,200.

Nicola Sturgeon's shoes: Scotland's opposition to fees is "writ in stane"

And the commission warned that the current system is financially unsustainable in the long term.

Anyone looking for international signposts for fee levels will find contradictory trends.

Germany has scrapped tuition fees altogether, while Australia is considering going in the opposite direction by allowing universities to charge whatever fees they want.

So what is the right level?

How do fees in England compare with European countries?

England has the highest tuition fees in the European Union (plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Montenegro and Turkey), according to an analysis of current charges by the European Commission.

It is an outlier with fees of up to £9,000 per year.

Other "relatively high fees" are charged in Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary and the Netherlands, with typical costs between about £800 to £4,000.

Jyvaskyla University, Finland: Nordic countries have rejected fees

Meanwhile Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Malta, Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, Scotland, Norway and Turkey do not charge fees for full-time students.

From this year, Germany's states have all stopped charging fees, with universities becoming state-funded.

Apart from a Nordic cultural resistance to fees, there isn't any clear pattern - and it suggests big questions lying ahead for European countries trying to fund rising numbers of students.

For evidence of the complete lack of consensus, look no further than the UK. England has the highest level of fees and Scotland is at the other extreme with none (at least for Scottish students). Wales and Northern Ireland are somewhere in between.

Not only is Scotland not charging fees for their own students, Alex Salmond attended a ceremony this week in which the pledge against fees was literally inscribed in rock.

"It is without doubt now a commitment writ in stane," said the First Minister.

How much is the support?

Fees are only half the story, because fair access to university also depends on levels of financial support.

The European Commission says England's repayment system is unique in Europe - with fee loans not paid back until after graduation and when earnings reach £21,000

Andreas Schleicher, the OECD's great guru of international education, has hailed this mechanism as a sustainable model for others to follow.

He has warned about some southern European countries having the worst of both worlds - with recession-hit governments cutting public funding and low fees starving higher education of investment.

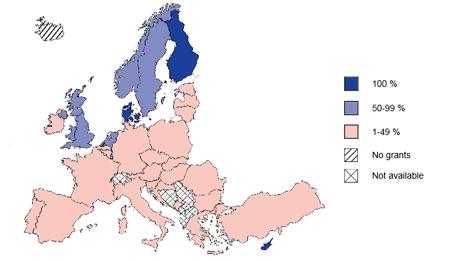

Percentage of students receiving grants. Source: Eurydice

The European Commission study has published this map showing a different pattern in terms of availability of support.

The Scandinavian model, reinforcing the concept of investment in education, couples high levels of support with no fees.

But England is seen to balance high fees with support for many more students than in a majority of other European countries.

What do university courses really cost?

Or to put it another way - how did it get to be £9,000?

The Browne Report, which ushered in higher fees in 2010, used the base figure of £6,100 for what universities would have to charge if the government withdrew its teaching grant.

With students rioting in the streets, Business Secretary Vince Cable promised there would be a "fee cap of £6,000, rising to £9,000 in exceptional circumstances".

It was originally claimed that universities would only charge £9,000 in "exceptional circumstances"

Then in a dash for cash, everyone turned out to be exceptional, and the £9,000 maximum became the standard charge.

But the cost of delivering courses vary widely. Science subjects, with many more classroom hours and with much more expensive equipment, are going to cost much more than arts subjects.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says if universities want to persuade the public and policy makers that they need higher fees, they need to show the evidence.

In particular he has highlighted Oxford University's claim that the real cost of an undergraduate course is £16,000 - calling on them to "show their workings" to explain this.

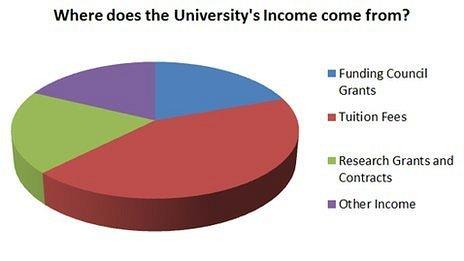

Leicester University has published a breakdown of its income

Leicester University is an honourable exception in showing students a breakdown of its income and how it spends its budget - £292m coming in and £285m going out.

It shows that the funding has to cover more than 3,000 staff and investment in "libraries, labs, computers and IT services, buildings and the campus estate".

It takes issue with the term "tuition fee", arguing that it suggests it's just about the cost of teaching, rather than the full campus experience.

And how much of the fee is really about the value of an enhanced career?

But that still doesn't provide much detail of the cost of individual courses - or the cross-subsidies below the headline figures.

Should the history student pay the same amount as a physicist? Should there be a clearer difference in price tags for different types of university?

What do you get for your money?

There can be a collective sharp of intake of breath when parents and their children are shown around universities on open days.

What takes them by surprise is the thorny topic of "contact hours", particularly for arts and humanities subjects.

Are students getting good value from their campus experience?

You can see them doing the sums, shiny brochure in hand. Five hours of face-time in seminars a week, maybe the same again in lectures with the rest of the year group. And that's how much per year?

And the official "Key Information Sets" which universities have to provide is far from transparent about such consumer-style detail.

How many hours will there be of seminars or small-group learning?

The Unistats website expresses this not in terms of hours and minutes - or any such old fashioned ways of measuring time - but as a percentage or a proportion compared with "independent study".

How many hours will there be in class? They're not making it easy to find out.

If fees are to rise again - and when there are new arrivals offering online learning - such a lofty approach to consumers will be harder to defend.

What would fees be like without limits?

There's a surprising league table published alongside the QS world university rankings.

It shows the world's top universities in terms of tuition fees - and for the UK the figures at first glance look more like US universities.

It's because these are the fees charged to overseas students, not restricted by the £9,000 upper limit.

This shows University of Cambridge charging almost £23,000 per year for a computer science course.

Fees vary between about £15,000 for subjects such as history and English up to more than £36,000 for medicine.

Is this an insight into how an unregulated, variable fees market might develop?

Higher fees are needed to keep up with US universities?

A resilient myth in the fees debate is that the wealth of top US universities is driven by their higher fees.

They do charge much higher fees - although the amount is often blurred because they include living costs alongside tuition fees.

Harvard's winning financial position is driven by investments not student fees

Harvard charges about $44,000 (£28,000) per year in tuition. But with extras such as board and lodge, it can be over $68,000 (£43,000).

These are daunting figures. But it's a misunderstanding to think of Harvard's finances in terms of tuition fees.

While the example for the University of Leicester showed tuition fees as the biggest source of university income, Harvard gets most of its money from investments.

It has a massive endowment - $36.4bn (£23bn) - and this is the engine of its wealth, underpinning an annual operating budget of $4.4bn (£2.8bn).

Even though the fees are high, they only represent a fifth of Harvard's operating revenue, a much smaller proportion than a university such as Leicester.

Harvard is far from typical - and less prestigious, less wealthy US universities are more dependent on fees.

But the major US universities, seen as global competitors for the UK, have finances built on multi-billion endowments as much as skyscraper fees.