The persistent appeal of grammar schools

- Published

Top of the Form, 1962: There are calls to open more grammar schools

What's behind the undying fascination with grammar schools? Four decades after almost all of them disappeared in England, there are still appeals for their return.

Many other types of school have disappeared, largely unmourned. Most secondary schools in England had gained "specialist" status, but that was washed away with a change of nameplate and a coat of paint.

But grammars - for their defenders and their opponents - have become part of the collective folklore of education.

A campaign to open a grammar in Sevenoaks - officially as an extension of another grammar school several miles away - could effectively see the first new grammar for half a century.

There are about 24,000 state schools in England and only 164 of these are grammar schools. But their impact remains much greater than their numbers.

Short back and sides

Is this just nostalgia for a short-back-and-sides style of education? Or, setting aside the arguments for and against grammar schools, does it tap into something deeper?

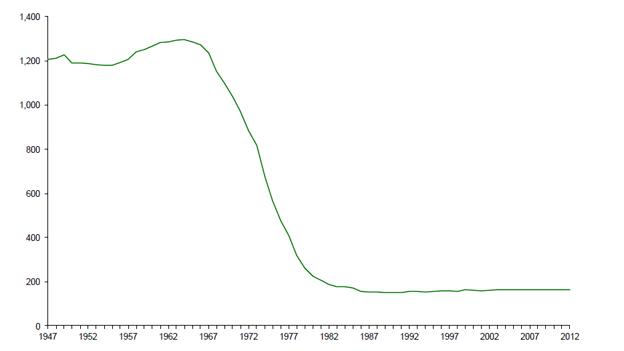

House of Commons library figures show grammar school numbers peaked in the mid-1960s

Perhaps the most radical thing about the grammar school system from today's perspective is that they didn't take into account where families lived.

It was based on passing the 11-plus test. The distance from school - the tape measure and estate agent system - was not the decider.

Research published this autumn by the University of Bristol's Centre for Market and Public Organisation, Cambridge University and the Institute for Fiscal Studies showed that basing admissions on closeness to a school was one of the biggest drivers of inequality between rich and poor families.

Prioritising school places based on the "size of your mortgage" was found to be a way of concentrating the poorest families in the worst-performing schools.

Apart from faith schools and experiments with lotteries, it has been very hard to find an alternative system that doesn't link school admissions to home address and house prices.

Social mobility

This has helped grammar schools to identify themselves with the cause of social mobility. The grassroots Conservative Voice group is calling for an expansion of grammar schools to "enhance social mobility and present parents with choice".

Alan Bennett's History Boys showed the conflicts and ambitions of grammar school pupils

This argument has been strenuously rejected by Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw, who says today's grammar schools are "stuffed full of middle-class kids".

Sir Michael says the grammar system was a great success for the small percentage who went to them, but terrible for everyone else.

That could also hit upon another reason that grammar schools have remained so stubbornly in the headlines. It's about the people who went to them.

"I think a lot of this is based on the very personal experience of individuals and anecdotal evidence. Many of the people who call for their return attended one and had a positive experience," says Brian Lightman, head of the ASCL head teachers' union.

The grammar school generation has provided a lot of good PR for the grammar school generation.

If the new public school elite are stereotyped as braying bulldozers, the image of grammar school pupils has been much more subtle and attractive. They were the amusing, intellectually-curious boys and girls from ordinary backgrounds climbing up the ladders of the professions and the arts.

It was Alan Bennett and black and white movies about clever, sharp-tongued youngsters shaking up the social order. They worked their way up in business, institutions and parties of both right and left.

When Michael Howard was Conservative leader one of his few successes against Tony Blair was his line on opening up access to university: "This grammar school boy will not take lessons from that public school boy."

Good timing

Another part of this glamour of grammars is that they coincided with a wave of post-war optimism and aspiration. Grammar schools were good with their timing.

Grammar schools peaked between the late-1940s and the late-1960s, with about a quarter of secondary pupils attending a grammar school during much of this time.

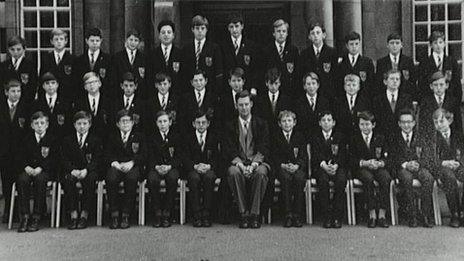

Class photo: Michael Portillo and Clive Anderson in their grammar school years

This was an era of rising living standards, higher ambitions, widening horizons and opening doors - and the memory of grammar schools is interwoven with those buoyant years. And as their numbers ebbed through the 1970s, it coincided with deepening economic upheaval and uncertainty.

They had their own history, traditions and identity, a curious mixture of local snobbery and classlessness, and when they were shut down their defenders saw this as a form of "vandalism".

But the great age of the grammars shouldn't be mistaken for a golden age in education.

In 1965-66, when grammars and secondary moderns were in full spate, only 18% of pupils achieved five O-level passes and 6% achieved three A-levels.

Perhaps even more sobering is that in 1980-81, only 25% reached five good O-levels and 10% left with three A-levels. There were also CSE exams taken, but they were seen as not being of equal value.

Such results now would seem catastrophic, when about four out of five pupils will achieve five good GCSEs. Many more people get university degrees now than would have gained five O-levels during the grammar school era.

Mythology

Russell Hobby, leader of the National Association of Head Teachers, suggests such evidence is overshadowed by the powerful mythology.

"A whole generation was told that grammar schools helped talented children from poorer homes climb the ladder. They were an engine of meritocracy in an age that took it seriously. With a myth that powerful, actual evidence is rarely required," said Mr Hobby.

Playing the game: Grammar school cricket match in 1963

But Graham Brady, Conservative MP and advocate of grammar schools, says that the remaining grammars show the high standards that such schools can achieve.

"Firstly, had everywhere gone comprehensive, there would be nothing with which to compare comprehensive local authorities: because we have some selective areas like Trafford, the comparisons are inevitable.

"Selective and part-selective authorities top the performance tables year after year. The other key is that many of us know from personal experience that grammar school gave us opportunities that are too often today limited to those who can afford a private education.

"That is why we see politics, the law, the senior civil service, even acting and the Olympics increasingly dominated by the products of public schools," said Mr Brady.

Grammars have also benefited from the turn of the wheel in how ambitious 21st Century schools present themselves.

The imagery of the grammar school, much of it borrowed from public schools, with crests, uniforms, prize-givings and house systems, has been adopted by many of the new academies.

It's as if being a high-quality secondary school now means looking like a traditional grammar school.

"Because these schools are selective they feature prominently in league tables and are therefore sometimes perceived to be superior to non-selective schools. What is often forgotten is that the return to a selective system would automatically exclude 80% of the population," says Mr Lightman.

Grammar schools have also benefited from a collective clouding of memory about their origin. The 1944 Education Act that paved the way for the new post-war education system really was for a different kind of world.

The aim of a state school system set out in the act doesn't even stress academic achievement. The purpose was the "spiritual, moral, mental, and physical development of the community".

As well as instituting prayers and free milk and banning fees, it gave local authorities powers to ensure the cleanliness of pupils if they were "infested with vermin or in a foul condition".

There were people in the Cabinet that pushed through this legislation who had left school at the age of 11.

International competition

The "tri-partite system" originally intended would have seen three equal types of schools, grammars, secondary moderns and technical schools. But the technical schools were never fully established and the 11-plus exam became a fork in the road between academic and non-academic pathways.

There are also misunderstandings about how grammars were abolished. Their closure - or more often their conversion into comprehensives or independent schools - took place under both Conservatives and Labour governments.

Grammars grew with the post-war welfare state: William Beveridge (centre) with Evelyn Waugh at the BBC

The pressure often came from the middle classes, whose expanding numbers were unable to get places in sought-after grammar schools.

But there was never any final conclusion, keeping the debate alive. Since the early 1980s the number of grammars in England has remained broadly unchanged. The Conservatives have not re-opened grammars and Labour has not shut any more down.

Perhaps the biggest argument against the wide-scale return of grammar schools is economic.

It was a system that assumed that only a small proportion would succeed in school - and it served a labour market where many jobs were available to the unskilled and uneducated.

Now all the big arguments are about how to catch up with Asian school systems, characterised by the expectation that almost all pupils should succeed. The economic arms race is about degrees for the many, rather than O-levels or GCSEs for the few.

Sir Michael Wilshaw, speaking about the rising interest in grammar schools, said: "Let's not delude ourselves. 'A grammar school in every town', as some are calling for, would also mean three secondary moderns in every town, too - a consequence rarely mentioned.

"What does the country need more of? Schools that educate only the top 20% of students, 90% of whom get good GCSEs, or schools that educate 100% of students, 80% of whom are capable of getting good GCSEs? I think the answer is pretty obvious."

Just don't expect the argument to go away.