Did £9,000 fees cut applications?

- Published

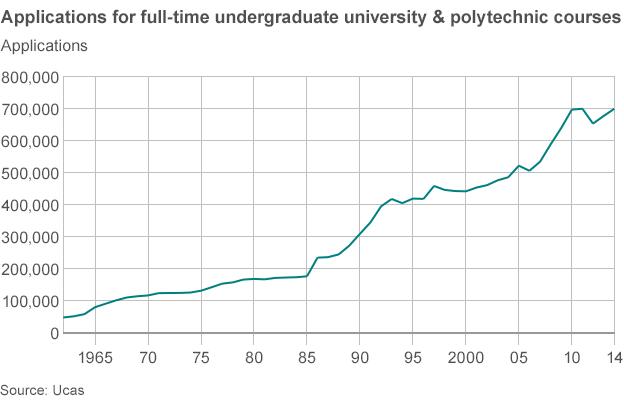

When tuition fees in England's universities rocketed to £9,000 per year, applications plunged in the opposite direction.

Applications slumped by the biggest ever amount, down by about 40,000 in England when they were introduced in 2012. It looked like thousands of young people were going to be frozen out of higher education.

But what happened next was less predictable. University applications bounced back. And with this year's deadline approaching on Thursday, they're climbing back to record levels again.

It looks as though the massive underlying demand for higher education has snow-ploughed its way through the financial barrier of trebling fees.

The huge expansion in university access over the past 50 years has been a quiet but relentless revolution - and this autumn more than 500,000 places were allocated for the first time.

The Ucas number crunchers say that applications are slightly below what they would have been if fees had not been increased, but not by much, and the long-term upward trend has returned.

Poorer students

The other big concern in 2012 was that poorer students would be the hardest hit by the higher fees.

But this has not followed the expected script. It's been the reverse. Instead of deterring disadvantaged students, there are more entering university now than when fees were lower.

The increase in tuition fees saw angry protests in the winter of 2010

Going to university has become a symbol of aspiration and families are willing to pay the price.

Rather like house prices, young people might not want the higher fees but they seemed to have gritted their teeth and taken on the debt, making the calculation that it was still better value than not having a degree.

Of course, there is still a cast-iron link between affluence and university entrance - the richer the family, the more likely that the child will go to university. But the rise in going to university has taken place across all social classes.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says that for "first-time full-time students, the system has worked out at least as well as anyone could have hoped".

And the international evidence suggests that the "apparently unstoppable demand will continue".

'Devastating'

But does that mean it's business as usual and nothing has changed? Not really. The impact has been reverberating in unexpected ways.

Aaron Porter was the high-profile leader of the National Union of Students in the tumultuous 2010 campaign against higher tuition fees.

Looking back he says that while applications have recovered for full-time undergraduates, there have been "devastating" consequences for other types of students, which have gone below the radar.

"Part-time students appear to be considerably more concerned about the price tag," said Mr Porter. "We have seen a chilling drop of 50% in part-time students since 2010. Had we seen anything like a 50% drop for full time students, the criticism would have been deafening."

There were more than 500,000 students allocated a place this autumn

Mature students, who might want to upgrade their work skills, have also been much more sensitive to higher fees, says Mr Porter, who is now head of external affairs at the National Centre for Universities and Business.

And the increase in fees represents a long-term threat to the pipeline of students needed for advanced, postgraduate research.

"So whilst on the surface, the recovery in demand for full-time undergraduate students is welcome, this is only part of the picture as they only comprise 56% of our student population. For the other 44%, the situation appears to have remained static and for many has worsened considerably," he says.

Opening the door

There are also big, far-reaching questions about the longer-term impact, such as opening the door to much higher, US-style fees.

Last week the UK's first private medical school opened at the University of Buckingham, charging tuition fees of £36,000 per year. The demand to study medicine is so strong that they haven't struggled to fill places.

But is charging over £162,000 for a medical degree going to widen the social gap? It's already a subject dominated by wealthier students, with the Office for Fair Access warning that only 4% of medical students are from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The first intake of students at the private medical school will be arriving this week

While the headline figure shows that poorer students are more likely to go into higher education, are they studying the same courses and at the same universities as richer students?

Instead of graduates being compared with non-graduates, will the social distinction become the type of university?

"It is incontrovertible that growth in participation in higher education by disadvantaged young people is disproportionately to lower tariff providers and through using BTECs," says the Ucas admission service's analysis of the 2014 intake.

And at the other end of the scale, richer students are seven times more likely than the poorest to get a place in "high tariff" universities, such as those belonging to the Russell Group.

Nick Hillman, who was special adviser to the former universities minister David Willetts, says that within the overall growth of higher education there could be "significant differences in recruitment patterns".

Different universities could have concentrations of different types of students.

Perhaps the focus on fees is looking in the wrong place entirely. Among the most remarkable changes in university applications in recent years has been the widening gender gap, with women much more likely to go to university than men. In a quarter of constituencies, there is a 50% difference or more.

Regional differences are another factor that cut across changes in fees. A woman in London is much more likely to apply to university than a man in the north east of England, even though they both face the same charges.

An analysis of parliamentary constituencies shows an average increase in entry rates of more than 20% since 2006 - but there are huge local differences. In 60 constituencies the increase has been more than 50% in the space of eight years - while in another 40 constituencies entry rates have fallen.

Building boom

Universities UK has set up a Student Funding Panel to examine future options for financing universities - and the evidence it has gathered suggests some other unexpected consequences from raising fees.

The biggest winner would seem to be the construction industry, with a survey reporting that 96% of universities are improving their buildings. Universities have to attract fee-paying students and shiny new buildings are part of the package.

University building boom: The University of Greenwich's new £76m building

In terms of losers, there are concerns about middle income families who miss out on the extra support for poorer students, but who struggle to afford the support needed by their children

It's often overlooked that the loans available for living costs can be much less than students need for their accommodation and food.

While the attention on funding is often about student fees, it can be their parents who are really facing the financial challenges. A study in the autumn claimed that hundreds of thousands of families were having to cut back on "basic outgoings" to cover the costs of their student children, such as rent and travel.

What is unavoidable is the sense that fees remain an unresolved issue. No-one is committed to the status quo.

There are universities pushing for an increase and students wanting to pay less.

The government will be anxious about the cost of lending, particularly with plans to expand student numbers.

And it remains uncertain whether Labour will promise a fee cut to £6,000 and whether that will be enough to impress people who remember when it was £3,000 or nothing at all.

The hike in price has not stopped the surge in demand for university, but tuition fees remain one of the most controversial issues in education.