How schools teach 11-year-olds about sexual consent

- Published

With children as young as 11 set to be taught in schools across England about sexual consent, the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme is given exclusive access to lessons.

"We need to provide opportunities for young people to think about what consent means, because they're going to face experiences in their lives which could involve sexual assault or even rape. That's a fact of life," says Phil Ward, head teacher of Heston Community School in Hounslow.

Children aged 14 and above at the west London school are already taught about sexual consent - but now those as young as 11, in Year 7, will be taking part in the lessons when they return to school after the Easter break.

The classes come at a "crucial" time, according to the PSHE Association, external, which developed the guidance for teachers, to try to keep sexually-active under-16s "healthy and safe from abuse and exploitation", without "encouraging under-age sexual activity",

Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures for England and Wales show in the 12 months to last September the police recorded more than 7,000 sexual assaults against children aged 13 or younger, and more than 4,000 rapes of children under 16.

It is an issue that teacher Natalie D'Lima confronts at the start of the lesson, making an explicit connection between consent and rape to ensure that students understand the relevance of what they are being taught.

Unlike Year 10 pupils, she explains, those in Year 7 are more likely to think of consent in terms of friendship groups, such as "seeking consent to misbehave or to look at someone's phone", rather than sexual relationships.

The PSHE Association suggests pupils between the ages of 11 and 16 should learn about the idea of consent in a "healthy relationship", where it must still be sought out and can be withdrawn at any moment.

Watch Victoria Derbyshire weekdays, 09:15-11:00 BST on BBC Two and BBC News Channel, for original stories, in-depth interviews and the issues at the heart of public debate.

Follow the programme on Facebook, external and Twitter, external, and find all our content online.

As the lesson continues, Ms D'Lima is keen to improve the children's grasp of what it means to give and receive consent.

Under her guidance, the pupils group into pairs. From three metres away, one child must edge continually closer to the other, before being asked to stop by their classmate once they feel uncomfortable.

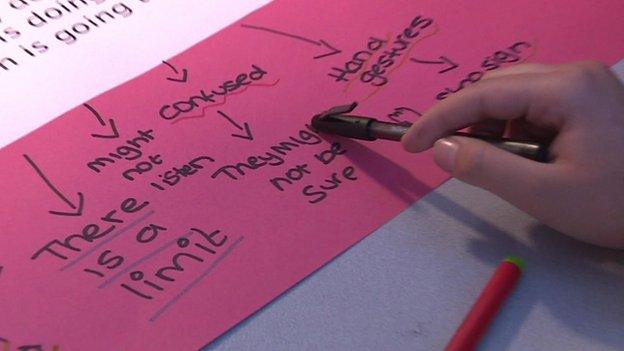

It became clear that while students understood the importance of personal space and boundaries, they were less clear about who was responsible for recognising the need for consent.

Only one pupil seemed to understand the concept, realising that it was the person moving forward who had to look for consent: "Maybe, they should know how the other one is feeling."

For the teacher, the children's lack of comprehension came as a surprise.

"A lot of them felt consent was a joint responsibility for both parties," she says.

"In future lessons we'll pick up on that and apply it to different contexts, so even though they didn't understand it in the context of them... approaching a partner, if we looked at it in terms of sexual relationships, hopefully they would pick up on that idea."

Nevertheless, the pupils seem to have taken away a key message on the importance of giving, and withholding, consent.

"If a stranger walks up to you and does something you don't like, I think you should have the confidence to tell him or her 'No'," says 12-year-old Ayesha.

"Saying 'No' doesn't mean you're being rude... it means that you don't like someone to be entering your personal space."

The government hopes the consent classes will be adopted in mixed and single-sex state and independent schools in every part of England.

But the plans have raised the issue of whether 11-year-olds are too young to be taught about sexual consent, and even whether such classes can place pressure on children to have sex.

It is a notion firmly rejected by the head teacher.

"[The classes] actually force students to reflect. It's a fact of life that people will come into situations we can't predict," Mr Ward says.

"Over time my students are going to grow up and they're going to be part of a real world where these things are going to be around, and they need to be provided with reflection time where they're able to make informed decisions about consent, should that situation arise."

Mr Ward emphasises the importance of discussing issues about sexual consent within the safe, nurturing environment that education provides.

But with schools in England free to decide whether such classes become part of their regular timetable, the big test for the government will be how many of them sign up.

- Published8 March 2015

- Published8 March 2015