What is the role of memory in a digital age?

- Published

If using search engines is allowed, would exams have to change?

How many of your family or friends' phone numbers can you remember off the top of your head?

I only ask because increasingly we all rely on our electronic devices to remember such information for us.

But when the idea of allowing students to use search engines in exams was suggested recently, the immediate fear was "dumbing down".

Only a few years ago, there was a similar debate about the use of calculators.

For the 11-year-olds sitting their national curriculum tests, often known as Sats, in England this week, the emphasis is on mental arithmetic.

Calculators are no longer permitted.

Their use will also be limited in the new GCSE maths exams, for which students will start studying this autumn.

No dictionaries

Dictionaries have had a similarly chequered track record in foreign language exams.

They were banned 15 years ago, after research suggested they gave the brightest students a greater advantage.

Newly redrafted GCSEs in French, Spanish and German will be introduced in 2016.

Calculators are no longer allowed for 11-year-olds sitting Sats

As part of its recent consultation on the exam, the regulator Ofqual has asked about the ban on dictionaries.

In the responses, opinion was divided, suggesting this is not a settled debate.

In different ways, these are all dilemmas about the boundary between knowledge and understanding, between retrieving information and manipulating it.

And with search engines, it is very much a digital conundrum.

Imagine for a moment the pre-digital equivalent - allowing students to roam through a vast library.

They simply would not have time to find the references they needed and return to their desk to complete the exam.

Now unimaginable amounts of information lie at our fingertips.

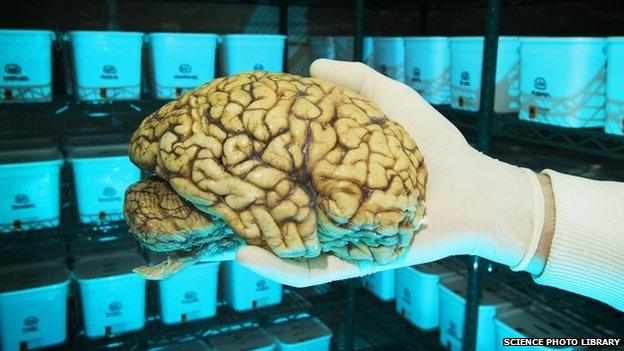

Scientists are studying how our brains are physically altered by how we use them

But does the act of memorising and then recalling information mould our brains in a different way?

Scientists are showing increasing interest in the life-long plasticity of the human brain and how its physical structure is altered by how we use it.

Learning that requires effort, and the use of that knowledge, might subtly alter mental development.

Some of the best known studies involve London's licensed black cab drivers, who have to memorise 25,000 city streets.

The process takes applicants between two and four years and many fail the final test, known as The Knowledge, because of its difficulty.

Researchers at University College, London, in 2006 studied the brains of 79 trainee taxi drivers and 31 non-taxi drivers, recording who had passed or failed The Knowledge and who had never studied.

It was a small sample.

But after four years, they found the taxi drivers' brain structure had altered, showing more grey matter in part of the hippocampus.

The hippocampus:

The part of the brain that is involved in memory forming, organizing, and storing.

It is a horseshoe-shaped structure, one part sitting on the left side of the brain, and the other on the right side.

It sends memories to the appropriate part of the brain for long-term storage, and retrieves them when needed.

In Alzheimer's disease, the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage.

So whether we learn and remember large amounts of information may quite literally shape our brains.

'No brainer'

The digital age is also raising broader philosophical questions about memory.

How much do we need to remember when it can be effortlessly recalled for us by a machine?

If the use of search engines for retrieving facts is allowed at some point in the future, exams themselves might have to change.

Allowing search engines in exams would test students' ability to assess new information, say proponents

Examiners would need to find ways of distinguishing between those students regurgitating information and those who could show how much they truly understood.

The chief executive of exam board OCR, Mark Dawe, says, external: "Exams have to be much more than a memory test."

He believes exams should assess ability to interpret and analyse information and that allowing the use of search engines is "a no brainer".

This may mean, for example, seeing how well students cope with being asked to research new subjects in exams - testing whether they select appropriate resource materials and how they apply what they find to what they already know.

Sceptics see a devaluing of traditional exam demands and question how effective such tests would be.

With tablet and smartphone use steadily rising, it is a debate that will continue to grow.

- Published14 May 2014

- Published30 April 2015

- Published8 December 2011