Poor white families feel 'abandoned', says Wilshaw

- Published

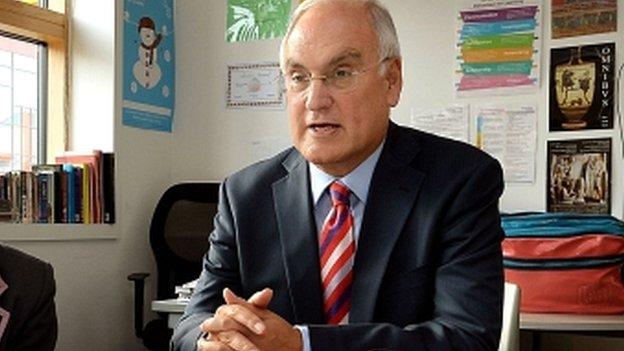

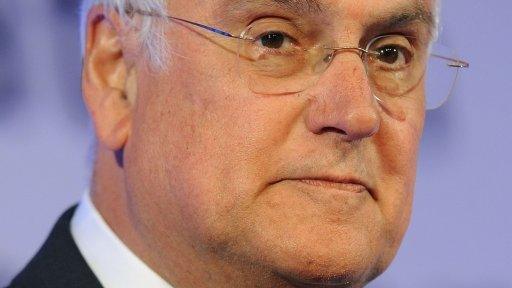

Sir Michael Wilshaw says he wanted to fine parents who did not support their children in school

White working-class families can feel "abandoned" and "forgotten" by the school system, Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw has said.

Poor, white communities needed to be served by better schools and school leaders, he said.

But parents also had a part to play, he said, and when he had been a head teacher he had often wished he could have fined "feckless" parents.

"It's up to heads to be challenging to parents," Sir Michael said.

And that included telling people they were "bad parents" and letting down their children.

Speaking at a Sutton Trust and Education Endowment Foundation summit in London, Sir Michael said the gap between rich and poor could not be narrowed without improvements in the results of disadvantaged white pupils.

"Two-thirds of pupils on free school meals come from white working-class, low-income backgrounds," he said.

"That's the greatest challenge. If we don't resolve that, we're not going to close the gap."

"They feel forgotten... they have been abandoned and let down."

Sir Michael said that these communities, including in coastal areas, were not getting access to enough good and outstanding schools.

"Even the most difficult, feckless parents, once they know a school is good and has high expectations, will usually support that school and do their best."

But Sir Michael said that heads had to be ready to challenge parents who were not supportive.

"I used to send very nasty letters to parents who didn't turn up to parents' evening - and say, 'You're not going to get your son or daughter's report until you come and see me.

"'You haven't turned up to a parents' evening three times on the trot.'

"On a number of occasions, I would say, 'You are a bad parent. You're not supporting your child.' And the reaction was not great sometimes. But it needs to be said.

"I would have loved to have had the legal backing to fine parents who did not support the school."

Secondary problems

Sir Michael said there were not enough good schools and there needed to be improvements in the supply of school leaders.

"The way we appoint head teachers is shambolic. It needs to be much more professional," he said.

There needed to be particular attention on weaknesses in secondary schools, said the Ofsted chief.

"There's a real problem in secondary schools at the moment, there's a real problem with progress and attainment," he said.

Raising standards for poorer pupils depended on getting more good teachers and heads, said Sir Michael,

But he robustly rejected suggestions that Ofsted could have a negative impact on schools.

"Anyone who thinks Ofsted should be abolished needs their head testing. As soon as our influence declines, you'll see standards decline," he said.

"Greater accountability has transformed the system, and children are getting a better deal."

In the 1970s and 1980s, standards in schools had been "dire", he said.

The summit heard how one head teacher was using pupil premium funding to make sure disadvantaged children did not play truant.

Dame Sharon Hollows, head of Charter Academy in Portsmouth, said she sent staff in cars to knock on doors and pick up children who had failed to come to school.

If they did not have the right uniform, she said, the school kept a supply of clothes for them to put on when they arrived.

Education Secretary Nicky Morgan also spoke at the summit.

She warned of the need to tackle the "quiet discrimination" of pupils from poorer families being pushed towards less academic subjects.

And she said pupil premium funding was now providing £2.5bn per year to help schools support disadvantaged pupils.

"We know there is more to do to tackle educational inequality. Too many people, and too many young people in particular, are still falling behind," said Mrs Morgan.

- Published27 May 2015

- Published30 June 2015