Can you make schools integrate?

- Published

David Cameron delivered his message against extremism in a speech at a school in Birmingham

David Cameron last week warned against the pernicious isolation that comes with "segregation" in schools.

"It cannot be right," the prime minister said, "that people can grow up and go to school and hardly ever come into meaningful contact with people from other backgrounds and faiths."

The context of the speech was tackling extremism - and his fear that "segregated schooling" would make it harder to stop the radicalising reach of a separatist Islamist ideology.

He warned of the risks of young people growing up in an inward-looking and disconnected environment.

But how do you really stop such segregation? Particularly when, as the prime minister's speech highlighted, schools can be more segregated than the neighbourhoods they serve.

This reflected recent research from the University of Bristol and the Demos think tank.

This showed a pattern of different ethnic groups tending to disproportionately concentrate in separate schools. In London, 90% of ethnic minority children were starting in schools in which ethnic minority pupils were the majority.

White pupils were disproportionately likely to be in schools with a white majority.

Self-segregation

The academics highlighted the places with the greatest segregation between white and ethnic minority pupils - headed by Blackburn, Bradford, Birmingham and Oldham.

Protesting against segregation in US schools in 1963

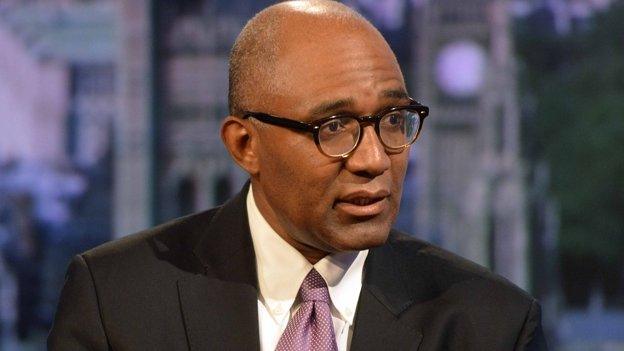

Among the most interesting commentary on this was from Trevor Phillips, former head of the Commission for Racial Equality, who said this wasn't about "terrible racial hostility".

Instead it reflected the cumulative outcome of many individual decisions, where families "unconsciously make a choice".

Education can bring out tribal instincts. Parents making school preferences are influenced by more than exam results, they want somewhere that feels right for their child - and that opens a whole set of questions about identity. Personal choice and calls for more integration can be pulling in different directions.

Where does a legitimate exercise of parental choice - over factors such as school ethos, the social mix of the intake, religious affiliation, mixed or single sex, private or state - turn into a form of self-segregation?

This isn't only a question in England's schools.

In France, with a centralised, secular education system, there were warnings from Prime Minister Manuel Valls about the emergence of segregated schools in which there were only children from "immigrant backgrounds, from the same culture and same religion".

Parallel lives

But trying to enforce integration causes its own problems.

In Beijing last week there were reports of Chinese parents staging protests against positive discrimination measures to give minority pupils more access to college places. The parents were angry that it would reduce chances for their own children.

Trevor Phillips says parents choosing separate schools is not about "terrible racial hostility"

Mr Cameron said tackling segregation would specifically not mean "busing" pupils, referring to the controversial policy in the United States of sending pupils across cities to create more racially mixed schools.

The US provides the biggest example of an attempt to enforce integration. And last year brought much attention to the question with the 60th anniversary of a landmark legal ruling that outlawed school segregation.

There was disappointment that abolishing segregation had not been the same thing as achieving integration.

While many of the set-piece battles against segregation were fought in southern states in the 1950s and 1960s, there were warnings that decades later in liberal, multicultural northern cities that schools were too often islands of separation, with communities living parallel lives.

In New York, research showed a pattern of black and Hispanic students taught in schools in which almost no white pupils were enrolled. These were accusingly labelled by campaigners as "apartheid schools".

In response there have been suggestions that schools should switch to admissions systems that deliberately construct a more diverse intake.

But there have been longstanding claims that enforced desegregation can be counter-productive and that busing had led to "white flight" rather than integration, with white families moving out from multicultural inner cities to the suburbs.

Muslim schools

A particular aspect of Mr Cameron's focus on segregation has been on religion, specifically the place of Muslims in the state school system.

What is most striking about the segregation data on faith schools is that Muslims do not have much of a place at all.

Blackburn was highlighted for a lack of integration in local schools

Of the 1.8 million children in faith schools in the state system in England, only 7,000 are in Muslim schools.

This doesn't mean that the demand goes away.

Without the option of regulated state Muslim schools, many families use low-fee private Islamic schools, operating outside the public sector. Among pupils attending Muslim schools, 91% are in private schools, compared with only 6% for Church of England or Catholic.

And a recent Ofsted report on pupils disappearing from school registers in Birmingham and east London suggested that some were switching to "unregistered" schools.

Perhaps they are seeking what Mr Cameron said was needed to deter radicalisation - a sense of "belonging". A sense of being somewhere where young people feel confident that they will fit in and where they will be safe in their identity.

A research project with schools in London, run by Kathryn Riley, professor of urban education at the UCL Institute of Education, is looking at ways to help pupils develop a sense of belonging.

The researchers say young people have a "deep-seated desire to be rooted and to belong" - and that schools need to find a way to make that work for pupils from many different backgrounds.

Mr Cameron put forward some ideas for building bridges - such as encouraging different schools to share facilities and teachers. He also proposed free schools with an integrated intake.

Brian Lightman, leader of the ASCL head teachers' union, backed calls to support schools with a "monocultural intake".

"In such cases it is really important that they are outward facing and enable young people to understand and empathise with the diversity which exists within the country as a whole," said Mr Lightman.

Expect to hear more about this balancing act between personal choice and collective identity when schools return in the autumn.

- Published6 July 2015