Exam results: It was different in my day...

- Published

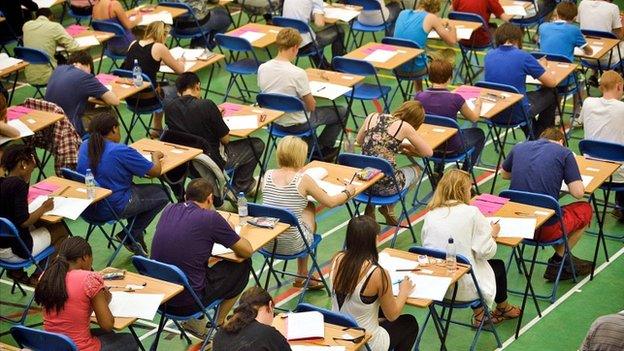

A-level results have become a public event

A-level results day has become an event in its own right, with a social media frenzy and its own annual rituals, embedded in the 24-hour news culture.

But it hasn't always been this way.

1. Envelope dropping through a letter box: That's how low-tech exam results used to be. No hugging, leaping, mass hysteria. No selfies, Tweets or Snapchats. People got their results often without going to school. The nearest thing to shared emotion was a few gruff words in the local under-age drinking pub, the Jam playing on a jukebox in the background.

Fast forward to the present and it's a storm of instant statistics, social media sharing and wall-to-wall coverage. There will be the first university admission figures, like the early results from a general election, followed by the ups and downs of this year's grades. As well as going into school to get results, pupils will be finding out their grades in every form of technology imaginable. Almost immediately universities will have their fingers on the send button to chase potential recruits.

2. Everything is public: There is no such thing as private grief in the digital glare of social media. Whether it's sharing results with friends on Instagram or parents emoting out loud on Facebook, the drama is played out in public. Teenagers have been messaging each other, building up the tension. There is no hiding place and it is tough for those with disappointing results. Social media has transformed the day into a shared event.

Greenwich University is ready to provide information by Skype

3. How exams were graded really was different: When Advanced levels were introduced in the early 1950s, there were only two outcomes, pass or fail. These were qualifications for a small top slice of the year group. Grades were introduced in the 1960s, with a fixed quota for each band. So the top 10% achieved an A grade, and then the next 15% a B grade and so on. It meant that even if the entire year group made more progress, the proportion of grades would remain the same. This system stayed in place until the mid-1980s.

4. Read all about it: Or in fact, you probably didn't, because under the previous system the national exam results were always the same. It's not much of a headline: "A-level results identical again."

When national results were no longer fixed quotas, it became more of a story - or more often a stick to beat the education system. Not much improvement was seen as standards stagnating. Too much improvement was labelled as "grade inflation". From one in 10 achieving an A grade in the early 1980s, one in four were getting top grades by the end of the 1990s.

When A-levels were launched in the 1950s there were only passes or fails, without any grades

It became a political event too. And when A-levels went wrong there was a price to pay. Grading problems in 2002 saw the exam chief losing his job and ultimately led to the resignation of Education Secretary Estelle Morris.

5. League table pressure: When the parents of today's A-level students were getting their results there were no league tables. Grades were not ammunition in a battle to perform better than other schools. Part of the ramping up of Results Day is that the stakes are much higher for schools. State and private schools and academy chains need to push up grades and want to publicise their successes, putting good news on to websites and press releases. Results Day has become a public showroom.

6. Advertising blizzard: Students are being targeted in a way that is entirely different from a generation ago. Universities are competing for students and their tuition fees and the weeks around the publication of results have become a marketing battleground. Websites, billboards, backs of buses are now carrying pitches for university courses. Every kind of digital marketing ploy will be aimed at potential recruits.

Results day has become a social media event, rather than an envelope landing on a doormat

7. Screen agers: Getting information about universities is now shaped around the needs of the screen-age teenager. It used to be a black-and-white, printed prospectus, where the nearest thing to multimedia was a picture of three spaced-out students in cheesecloth sitting under a tree. But now universities are open in every way, whether it's online chatrooms or, in the case of the University of Greenwich, advice by Skype for students who might be away on holiday.

8. Big numbers: Another huge difference is the increase in numbers of people taking A-levels and waiting to hear about university places. In the early 1980s only about one in 10 students achieved three A-levels. Now it's a much more mainstream event. The expansion in A-levels has gone hand in hand with the expansion in higher education. More students will begin university courses this autumn than were getting five good GCSEs two decades ago.

9. Headline act: A-level results have become a news event, but are rising results good news or bad news? An academic study of media coverage of A-level results included some classic headlines from 2003: "On a joyous day, dissenting note from an ex-examiner: We're all deluding ourselves," said the Daily Mail. "A-levels will be a success when more pupils fail," said the Sunday Times. But the Guardian questioned: "Where is the proof of a fall in standards?"

10. Results day rituals: Exam results day has developed its own mid-summer rituals. The most famous has been the front-page pictures of blonde female students leaping in celebration. It had become such a widely-mocked cliche that last year The Times published its own ironic version on its front cover with four leaping boys showing their midriffs. Expect stories about high-achieving twins, youngsters overcoming adversity and pictures of people shouting into mobile phones.

- Published13 August 2015

- Published13 August 2015