Head teachers also face results day nerves

- Published

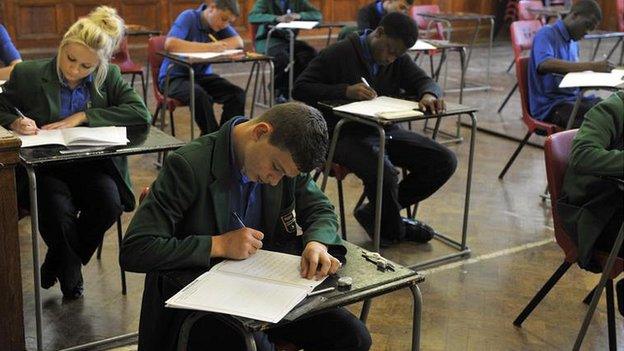

Jules White says the approach of exam results means a growing sense of anxiety for heads

Pupils and their families have had an anxious wait for GCSE results. But what's it like for head teachers? Jules White, a head from West Sussex, describes the pressure.

They say that you should never work with children or animals - the results are too unpredictable. With two teenagers and a couple of poorly-behaved dogs galloping around my house, I should understand the truth of this as well as most people.

Perhaps I should know it better than anyone because I am also a secondary head teacher and when August rolls around, the truth of this old adage always rings louder still.

The summer holidays are great but as time goes by the fear increases and a faint sense of nausea rises to full-on sickness - GCSE results day is close at hand.

Let's get a touch of mea culpa out of the way first. I am by nature intensely competitive, always wanting to do better than the rest.

It used to be in sports, but more recently I have found different league tables to focus upon. Throw in too an unhealthy dose of anxiety about letting down students, their families and colleagues, and an unpleasant cocktail is placed on order.

Disturbingly, a string of "gold medal" performances from students and staff at our school has not allowed these fears to subside.

Disturbed sleep

Over recent years, I have become all too familiar with some turbulent emotions which affect my sleep patterns by night and an ability to fully relax by day.

If I am generating any sympathy then spare a thought for the others too - because I am not alone.

Head teachers across the country also face pressure as exam results arrive

You see, to a greater or lesser extent, all heads worry about their results. They reflect years of education and everyone's hard work. The future of students - and many head teachers - often rest upon them.

Schools get the results a day before they are given to the students.

During the wait for their arrival, different heads cope in different ways. My closest head teacher colleague takes on the role of expectant father and paces the streets until the results download is completed by his assistant head.

The assistant head calls at approximately 3am with the headline figures. Only then can the head take some genuine rest.

Some heads are away in far-flung places and wait anxiously by their phone for scores to come in. Others log on in the very small hours hoping for an early data release. Then, there are those like me, who meet with anxious senior colleagues for a 6am "results breakfast".

So is it all down to a lack of steel and a desire to avoid reasonable levels of accountability? I don't think that it is that simple.

Our anxieties are fuelled by what seems to many heads to be an unhelpful mixture of an unreliable exam system which in turn services an equally unpredictable inspections system.

The facts are difficult to contest. Last year more than 45,000 exam grades were changed after schools challenged the results.

In 2012, matters seemed to have come to a head when schools up and down the country found that crucial English and maths results often bore no relation to expected outcomes.

Inspection fears

Many head teachers are uncertain as to how overall grade allocations are made and frankly pronouncements from Ofqual the exam regulator are frequently as clear as mud.

Heads are contacted in July with an overview of exam entry patterns and potential grading anomalies. To me, these letters merely add to a sense of unpredictability rather than bringing clarity to an already murky system.

Then there is Ofsted. Too often weak inspection teams seem to place an undue emphasis on a fleeting set of annual results. Trends over time can be overlooked.

This can cut both ways, as some underperforming schools seem to leap to "good" or "outstanding" on the back of favourable results. Other high-quality schools can fall foul of a poor judgement following one year's indifferent performance.

It won't have offered much reassurance to heads waiting for results that this summer more than a thousand inspectors were themselves found to be not good enough.

Some improvements are at hand. There are plans to measure schools across a wider basket of subjects, which would be a step in the right direction, as is the removal of inflated scores gained from some vocational qualifications.

But from the perspective of a head teacher, more is still required for a robust and transparent exam system, so that everyone involved knows what is expected. There needs to be attention to consistency and clarity as well as "rigour".

We must also think more about the purpose of examinations. Is removing coursework and independent study the right way to prepare young people for the modern workplace?

As the GCSE results approach I will tell myself to stop worrying quite so much and to keep things in perspective. But there would need to be some changes before I could take this advice on board.

Jules White, is head teacher of Tanbridge House School in Horsham, West Sussex. The school achieved 76% of pupils achieving grades A* to C in at least five subjects, including English and maths