Why are coastal schools at such a low ebb?

- Published

Seaside towns have faced rising tides of deprivation

Is where you live the key defining feature in being in an underachieving school? Is geography the new poverty?

The rise of London as an education superpower, succeeding despite high levels of deprivation, has redrawn the map of expectations in school achievement.

And where once there used to be generalisations about the problems of schools in the "inner cities", the attention has now switched to coastal towns.

The fading seaside towns, with unreliable transport links and local economies as rattled as a pier in a gale, have become a growing cause for concern for education ministers and inspectors.

But why should schools in coastal areas struggle?

Setting suns

Instead of sunny postcard images, a report last month from the Future Leaders Trust, external described towns on the coast in terms of geographically isolated communities based around declining industries.

The optimism of seaside towns has receded into concerns about declining industries

The charity, which works for fairer opportunities in school, says there is a culture in "which students are given limited experience beyond their own town and where they see little value in academic qualifications".

Even though there are wide horizons of the sea, economic perspectives are narrow.

The Trust's report argues that "exceptional head teachers" need to be recruited and deployed to seaside towns.

The struggle to get enough good teachers has been cited as a major problem for coastal schools.

Summer in Cornwall

There is a staffing problem for all kinds of schools in England - and coastal towns face particular difficulties in competing.

They can't offer the attractions and good transport links of big cities and they don't have the more comfortable surroundings of the well-upholstered suburbs or shires.

End of the pier

In response, Teach First, set up to bring top graduates into classrooms in struggling inner-city schools, has now turned its missionary zeal to places such as the Isle of Wight, Great Yarmouth, Blackpool and Thanet.

The charity built to tackle urban deprivation is now beside the seaside.

Coastal schools are also more likely to serve groups of youngsters associated with lower achievement. There are higher concentrations of white working-class pupils, often the lowest achieving in exam results.

Tanya Ovenden-Hope from Plymouth University, who has studied coastal academies, identifies an inter-generational lack of engagement. Parents who themselves had a poor experience of education have low levels of expectation that it will offer much more to their own children.

Half-term in Llandudno

Populations can be transient, with seasonal work and families that move in and out of the area. The grand Victorian and Edwardian seaside villas have often been chopped up into bedsits, bed and breakfasts and temporary accommodation.

Seaside towns have lacked the jobs that will attract and keep bright young graduates, so talented youngsters are less likely to remain.

Isolation

Towns relying on tourism have faced tough times and it's been far from plain sailing for communities based around shipping or fishing.

And high-skill, high-tech industries have clustered around universities or big city start-up hubs rather than at the end of a coast road.

Seasides have struggled to keep up with economic change: Eastbourne in 1950

A 2013 report from the Centre for Social Justice, external described seaside towns as "dumping grounds" for social problems, with just five towns - Rhyl, Margate, Clacton-on-Sea, Blackpool and Great Yarmouth - costing £365m per year in benefits and housing support for working-age adults.

Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw has defined the problem for schools as being about "isolation".

As well as being physically isolated, he says that too often coastal schools are cut off from the help they need and the pressure to do better.

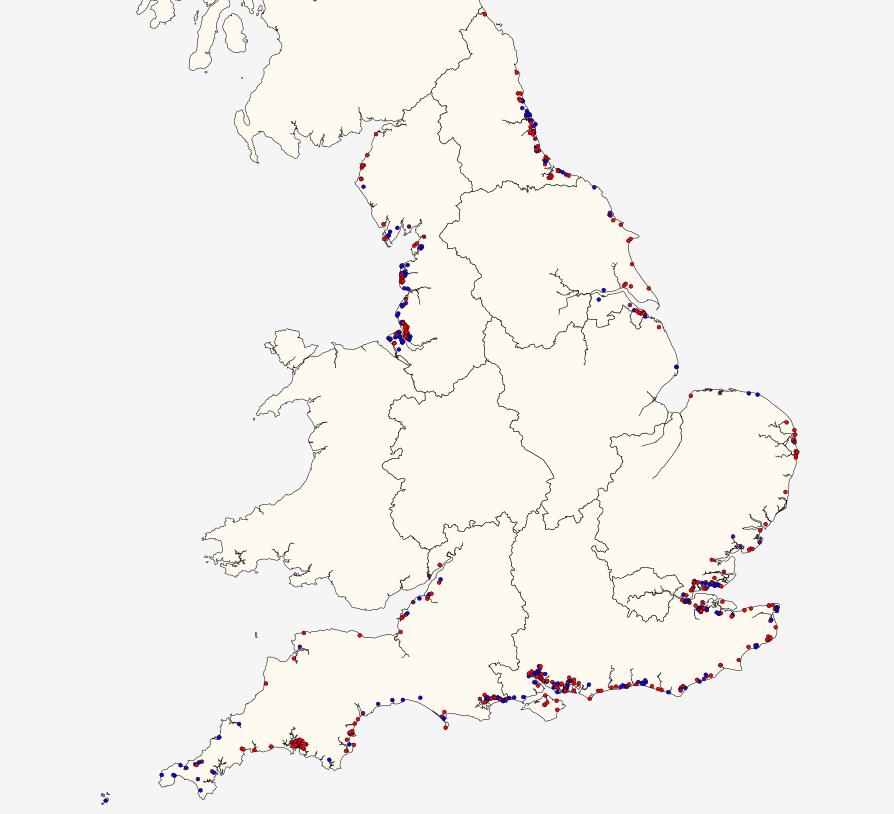

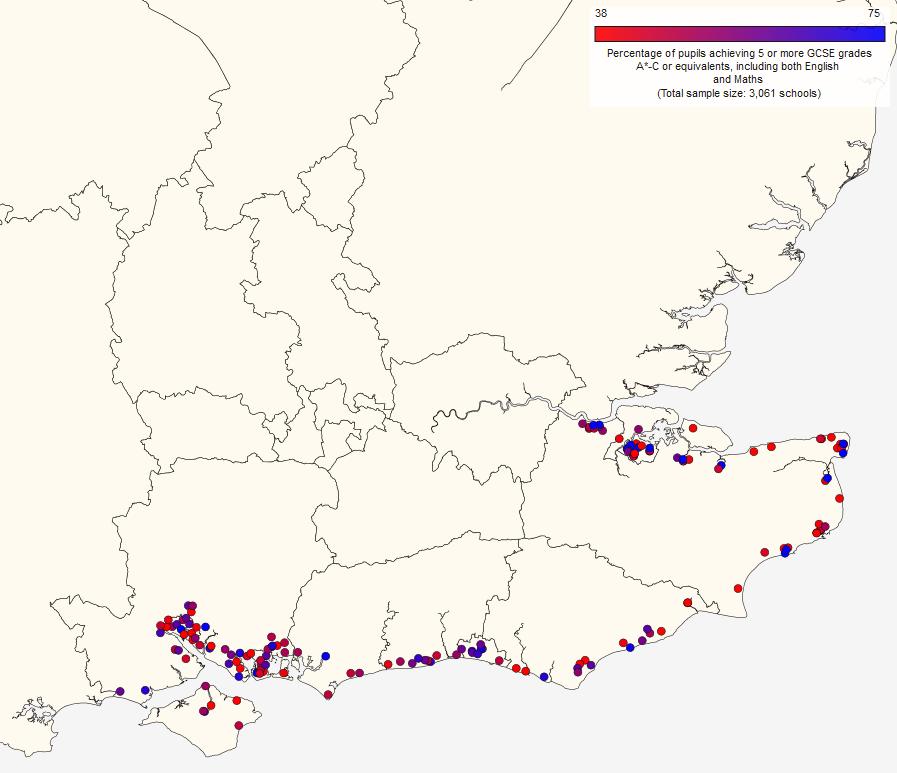

A mixed picture for coastal schools, with red dots showing weaker GCSE results

"These schools are deprived of effective support when times are bad. They are left unchallenged when they flirt with complacency," said Sir Michael, launching last year's annual report.

It's another organisational version of being bypassed.

Lower results

And there is some fascinating number crunching showing that coastal schools are not catching up.

SchoolDash, external, which analyses education data, has examined the performance of coastal schools, external in this year's provisional GCSE results.

The redder dots are lower achieving schools, mapped by the SchoolDash website

And these figures from summer 2015 show that pupils in coastal schools are on average achieving 3% lower results than inland schools, based on the benchmark five good GCSEs including English and maths.

This might seem narrow, but in exam results it is quite significant when annual changes are measured in a fraction of a percentage point.

And the summer results for coastal schools, at least provisionally, are lower than in any of the previous four years and consistently below the average for inland schools. There are no signs of results rising.

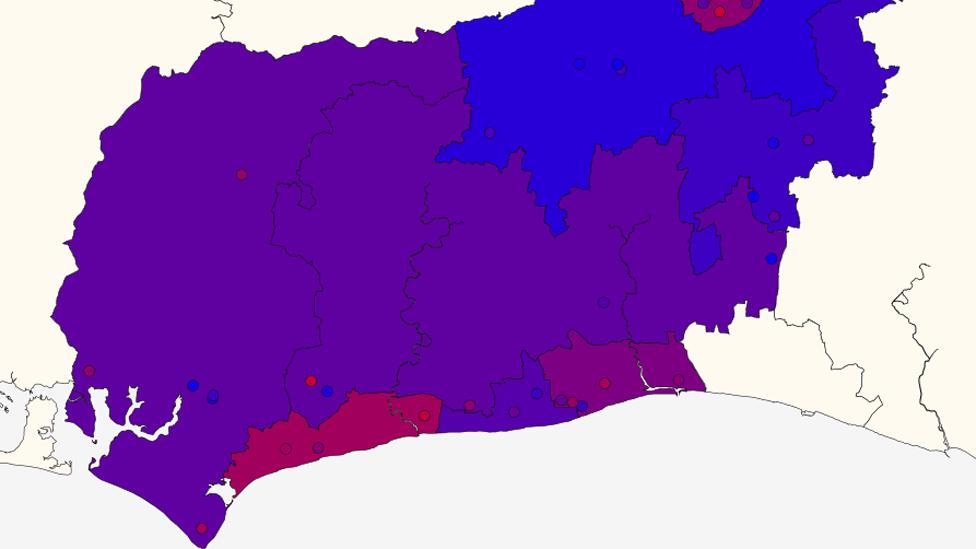

West Sussex shows a coastal strip of weaker results in red, rising through purple to blue

If the coastal schools were counted as a separate region they would be below average, but ahead of England's lowest-performing regions, the north east, Yorkshire and the Humber and the east Midlands.

The figures also show that coastal schools have a more deprived intake, with 3% more pupils eligible for free school meals - a figure similar to the achievement gap.

There are exceptions. The SchoolDash data shows that places such as North Tyneside and Lancashire coastal schools outperform their inland counterparts. And there are some coastal areas which are conspicuously affluent.

But the national picture shows a trend of overall lower performance in coastal schools. And as you focus more tightly, a map of the south east, external shows pockets of underachievement pinned around the coastline.

And if you go in closer again, such as a map of West Sussex, external, there is a discernible trend for a strip of lower results on the coast and then rising further inland.

Is this really all about poverty, but made more poignant by the trappings of seaside optimism? Is it about communities left behind by changing times?

And why are more deprived areas of London much more successful and ambitious?

Like a grabbing crane in one of those arcade games, always missing out on the top prize, it's proving difficult to pick up the right answer.

- Published5 August 2013