Academy plan 'a huge political gamble'

- Published

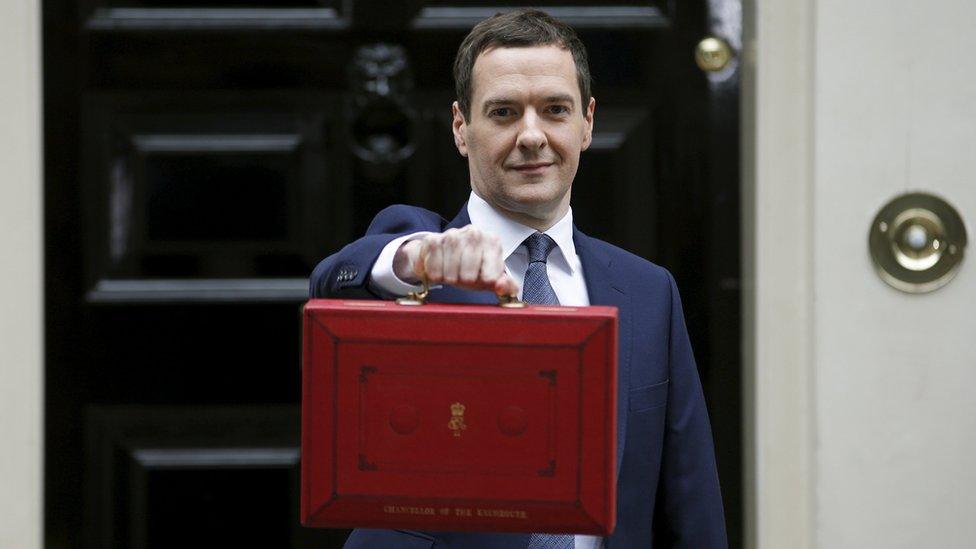

George Osborne is expected to make the announcement in his Budget

In pressing ahead with plans for all state schools in England to become academies George Osborne is taking a huge political gamble.

Large-scale change of public services is high-risk because so many people engage with them.

There will be angry opposition from boroughs - some of them Tory-led - where schools are good.

Already they're asking: where is the evidence that becoming an academy - independent, state-funded schools, which receive their funding directly from central government, rather than through a local authority - is a one-way ticket to better schools? Some flourish and excel, but others have failed.

The first academies were schools in dire straits, the next big slice converted for cash, and a law to force underperforming or "coasting" schools has just gone through Parliament.

Currently, 2,075 out of 3,381 secondary schools are academies, while 2,440 of 16,766 primary schools have academy status.

Compelling good schools to go down the same road will prompt that age-old question: "if it's not broke, why fix it"?

Innovation

The case in favour is that it puts power to make decisions in the hands of head teachers - or rather the chief executives who now run chains of publicly-funded schools across England.

There is more leeway for innovation, but for the moment that's been modest. Most still broadly follow the national curriculum.

Secondary schools are under a lot of pressure to meet targets

Schools are judged on highly centralised performance measures, such as pass rates in the core traditional subjects in the new English baccalaureate (a good GCSE in English, a language, maths, science and history or geography).

The wriggle room for risk-taking and innovation is limited when head teachers are also looking over their shoulders at league tables and the next Ofsted inspection.

None of this means interesting variety and innovation won't happen in the long term. There will be more schools that educate children from the age of 5 to 18 for example. That could increase the incentive at every stage to focus on children at every level of ability, rather than those who can be most easily helped over the hurdle of getting five good GCSEs.

Osborne's plans will face some practical hurdles too. Where are the queues of sponsors who want to set up new multi-academy trusts in England?

Many of the existing trusts will also be occupied in opening new schools to meet that other core government pledge of 500 extra free schools by 2020.

A solution of some kind will also have to be found for schools that have expensive private finance initiative (PFI) payments at a time of tightening public finances. Unless some way of managing that cost is found, there could be some schools that no one wants to take on.

Regional Schools Commissioners

These plans will shift accountability for the quality of schools from locally elected councils to eight Regional Schools Commissioners in England.

Most parents don't know of their existence, let alone who they are.

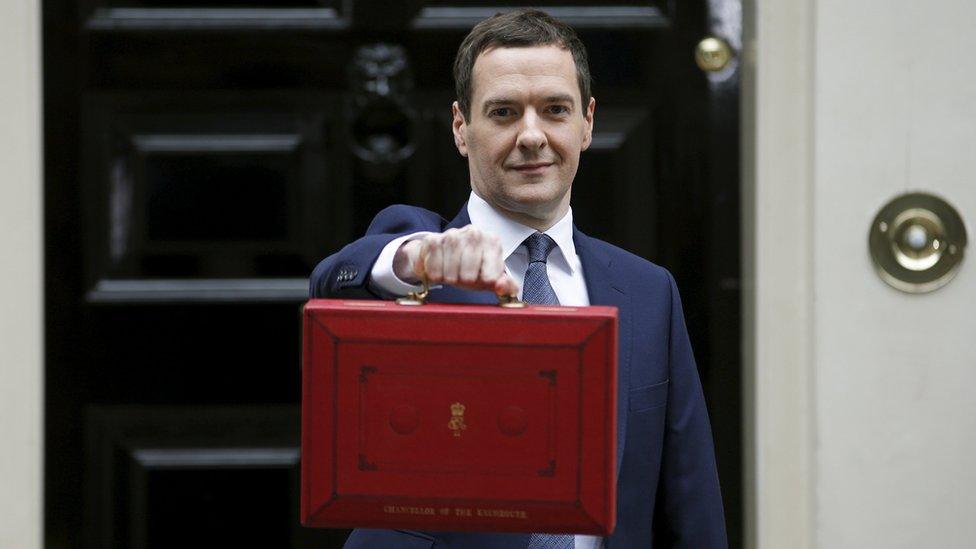

Mr Osborne's announcement will see more primaries becoming academies

Each will be responsible for overseeing thousands of schools and intervening where they are faltering.

It's a tough job, and there have been questions about whether their decision-making process will be transparent and open.

Multi-academy trusts will also have to keep on demonstrating that they are open to scrutiny. An investigation by the charity commission into one has yet to report.

Another recently announced it was going to get rid of the role of local parent governors in individual schools.

So will the gamble pay off? There is quite honestly no way of knowing, certainly not by the time of the next election.

But these changes do mark a fundamental shift in the way publicly funded education is run and held to account in England. It's a big step away from the publicly funded and managed school services in every other part of the UK.

- Published16 March 2016

- Published7 May 2016