Do academies get better results?

- Published

A study shows weaker schools are the most likely to benefit from academy status

If a school becomes an academy are the results more likely to improve?

It's a key question in the debate about whether all schools in England should be forced to become academies, but the answer often seems frustratingly unclear.

An independent education data firm has carried out an analysis in an attempt to get an answer.

SchoolDash created a sample of secondary academies and local authority schools with similar characteristics to see how their exam results compare, external.

And the short answer is: Sometimes academies do better, sometimes not.

So what's the problem with getting a more definitive answer?

Almost two in three secondary schools in England are now academies - but it's become a term that is applied to very different types of school.

It's like using the same term to describe football teams in the promotion and relegation zones.

Nicky Morgan says she will not reverse away from compelling all schools to become academies

About 70% of secondary academies are known as "converter" academies - and these schools were usually doing well before they became academies.

For these academies, the SchoolDash analysis says there is no discernible pattern of any impact on results.

Based on raw averages - and because of the greater numbers of converter academies - this wouldn't show much of a positive story for overall academy results.

But there is another smaller group of "sponsored" academies, often drawn from schools in need of improvement.

Rather than look at these two types of academy together, this analysis treats the sponsored academies separately, and this finds a more positive impact.

Timo Hannay, founder of SchoolDash, says these schools on average do seem to make greater progress in GCSE results than local authority schools with a similar intake of pupils.

The NUT's conference this Easter voted to challenge the academy plans

Taking a sample of schools which converted to academy status between 2010 and 2012, there were 3.6% more pupils achieving five good GCSEs including English and maths than comparable local authority schools.

There is also a greater improvement among disadvantaged pupils.

"GCSE results suggest that converting already high-performing schools to academies has little effect on their academic performance, so it's not true to think that academy conversion raises standards across the board," says Mr Hannay.

"But neither is it true to claim that it has no effect because it does seem to help previously under-achieving schools."

Mr Hannay says that the academy process seems to make it more likely that weak schools will catch up.

"This gives us reason to believe that it might help to reduce the gap between the best and worst schools."

And he says, setting aside the question of how they might have also improved under a local authority, the results suggest "good schools staying good and bad schools getting better".

Even with this finding there are some big factors muddying the waters.

As well as the different types of academy, there is the question of the academy chains which run groups of academies.

Ofsted has shown that academy chains, like local authorities, can vary widely in quality, with good, bad and the ugly. The success or otherwise of an individual academy can be hard to separate from the performance of the academy chain to which they have been assigned and which they cannot choose to leave.

George Osborne announced the compulsory academy plan in the Budget

Another factor fogging up any simple evaluation is that many academies have only been academies for a short period of time.

Will the performance of the first wave of schools choosing to become academies be the same for those subsequently forced to become academies?

For sponsored academies, it might be possible to jump-start improvements in a failing school, but can that be sustained over time?

And how will the academy process work for primary schools, which so far have been slow to convert.

It remains another great unknown how every primary school, from the inner cities to remote villages, will be allocated to academy chains. This is a massive shift - outsourcing thousands of local schools to chains most of which have yet to be created.

After the converter and sponsored academies, this new group of forced academies will be by far the biggest.

And not surprisingly there has been a big ideological divide in the response, with the government's commitment to academies matched by the teachers' unions' scepticism.

There are also mutterings of disquiet from Conservatives in local government.

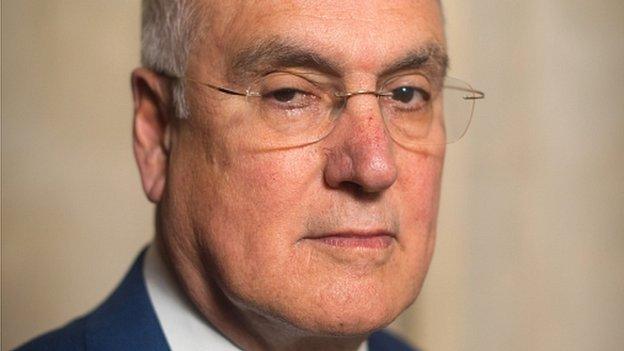

Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw has warned of the variable quality of academy chains

They might look further down the tracks to future administrations and wonder what will be the implications when all schools - including village schools, grammar schools and faith schools - will be academies overseen by Whitehall-appointed regional schools commissioners.

Parents, often not bothered about school labels, will look for the clear-cut evidence supporting such a one-size-fits-all solution.

And high-achieving schools, run by good local authorities, might wonder what problem is being solved?

Mr Hannay, researching secondary results, says: "We don't yet know what effect it will have on the bulk of moderately good secondary schools that are now being required to convert.

"This analysis suggests that any changes in GCSE attainment are likely to be modest, or possibly absent altogether, but unlikely to be detrimental."

- Published14 February 2016

- Published1 February 2016

- Published21 May 2014