Why do women get more university places?

- Published

A majority of young women in the UK are now entering higher education

Why are women getting so many more university places than men?

This isn't just a slight difference. Women in the UK are now 35% more likely than men to go to university and the gap is widening every year.

A baby girl born in 2016 will be 75% more likely to go to university than a boy, if current trends continue.

The Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) has published research examining this increasingly polarised gender divide.

And as university remains the gateway to better-paid, more secure jobs, Mary Curnock Cook, head of the Ucas university admissions service, warns that being male could be a new form of disadvantage.

"On current trends, the gap between rich and poor will be eclipsed by the gap between males and females within a decade," she writes in an introduction to the report.

And she says while there is much focus on social mobility and geographical differences, there is a collective blind spot on the underachievement of young men.

Women gain greater financial benefits from getting a degree

So what is causing such a pattern?

The likelihood of going to university is shaped by results in primary and secondary school - and girls are now outperforming boys at every stage.

But the report demolishes one long-held theory - that this success for girls was triggered by the switch from O-levels to GCSEs in the late 1980s in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

There have been claims that the gladiatorial, all-or-nothing exam worked in favour of boys, and that the greater sustained effort of coursework favoured girls.

And this theory seemed to fit with when women overtook men in university places in the early 1990s.

Is the male student heading towards extinction?

But the report finds that such connections are "overcooked" - and that by the time the exams were changed, women had already almost caught up with men in university entry rates and this trend pre-dated the shift to GCSEs.

This was also an international trend, suggesting wider factors than changes to local exam systems.

Ms Curnock Cook says she is "instinctively convinced" the fall in the proportion of male students is connected to the increasing gender imbalance in the school workforce.

Until the early 1990s, most secondary school teachers were male. This has now completely reversed, with the teaching profession becoming increasingly female.

Are young men not getting enough educational role models?

Four out of five universities now have more women than men students

But the research report, written by Nick Hillman and Nicholas Robinson, says the evidence remains unclear about whether such a female workforce has a negative impact on male students.

What is incontrovertible is that women have taken the greatest advantage of the rapid expansion in university numbers in the 1990s.

In 1990, there were 34,000 women graduating from UK universities, compared with 43,000 men. By 2000, the positions were reversed, with 133,000 women graduating, compared with 110,000 men.

In the following years the gap has accelerated - so that the most recent figures from last year show there were almost 300,000 more women in higher education than men.

Five out of six higher education institutions now have more female students than male - and if every single man who applied to university were to be automatically given a place, there would still be fewer men than women.

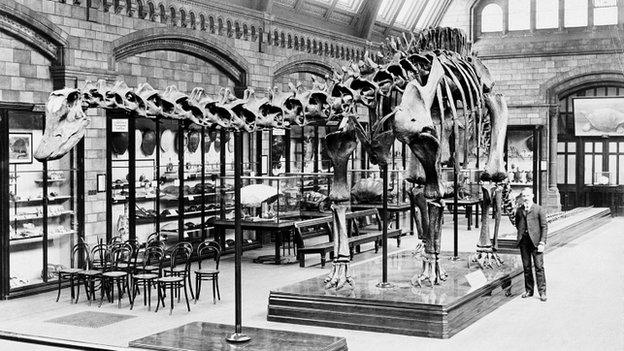

The first GCSE year in 1988: the study rejects the idea that the shift away from O-levels helped girls

But there are substantial underlying differences within the male population.

Among white boys from disadvantaged families only about 10% will go to university - the lowest of any social or ethnic group.

Deprived boys from other ethnic backgrounds, such as black and Asian, are much more likely to go to university.

This suggests different barriers in attitude and expectation. And it suggests some communities have been left behind, as industries and expectations have changed around them.

Or perhaps boys are just less well disposed to studying.

The report includes OECD data, gathered alongside international Pisa tests, that shows on average that boys are less likely to work hard at school, less likely to read for pleasure and more likely to be negative towards school and to dodge their homework.

Another theory for women's record levels of success is that they get much more benefit from going to university.

The study says it is "economically rational behaviour" because women are particularly likely to gain financial benefits from getting a degree.

The gap in earnings between female graduates and non-graduates is much greater than the earnings gap between male graduates and non-graduates.

Another way of interpreting the rise of female graduates is to look at changes in the jobs requiring degrees.

Female-dominated professions - if you took prospective teachers and nurses out of university student numbers, the gender gap would narrow

When training for nursing moved from diploma to degree level it brought a large, female-dominated group of trainees into the higher education sector.

If two sets of students were removed from the figures - nursing and teacher training - a substantial proportion of the gender gap would disappear.

The report looks at the tougher question of what should be the response.

The Scottish Funding Council has set targets for Scottish universities to stop "extreme gender imbalance" so that no subject by 2030 should have less than 25% of one gender.

There are also suggestions that young men develop more slowly - and could benefit from a delayed entry or the equivalent of a foundation year.

Should universities have recruitment targets for male students, in the way that they have outreach projects for other under-represented groups?

Report author and HEPI director Nick Hillman says: "Nearly everyone seems to have a vague sense that our education system is letting young men down, but there are few detailed studies of the problem and almost no clear policy recommendations on what to do about it.

"Young men are much less likely to enter higher education, are more likely to drop out and are less likely to secure a top degree than women. Yet, aside from initial teacher training, only two higher education institutions currently have a specific target to recruit more male students. That is a serious problem that we need to tackle."

Universities Minister Jo Johnson said: "While we are seeing record application rates from disadvantaged backgrounds, this report shows that too many are still missing out.

"That is why our recent university access guidance for the first time called for specific support for white boys from the poorest homes."