Why do more women than men go to university?

- Published

This year 75% of boys' entries were graded A* to C compared to nearly 80% of girls' entries

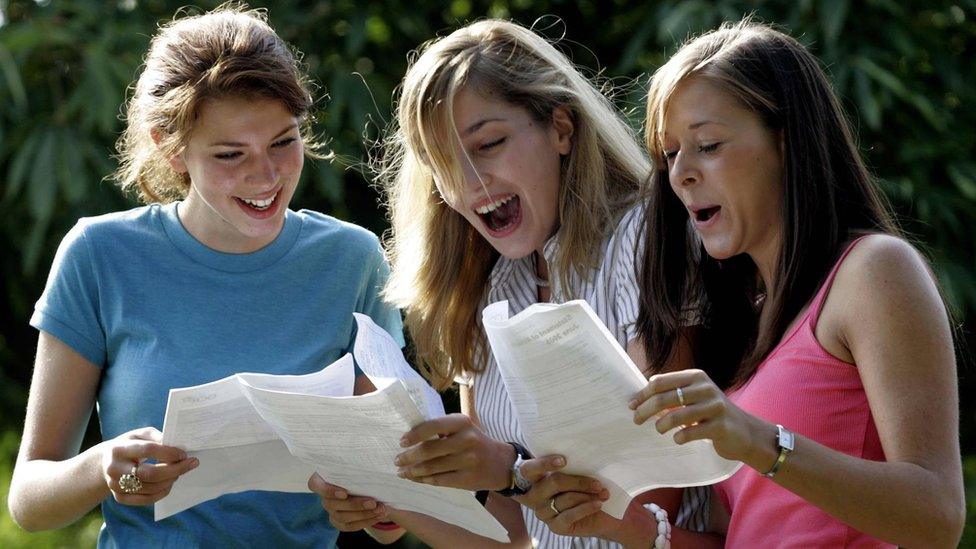

It is the cliched newspaper picture of exam success - three girls smiling incredulously or jumping for joy at how well they have done.

But like all good cliches, there is more than a grain of truth in these typical snapshots of A-level results day.

Girls do better than boys at A-levels (or Highers in Scotland), and indeed at every level of education.

So, with A-level grades the main qualifications for university, it is hardly surprising that women are now far more likely than men to go there.

This year nearly 80% of girls' entries were graded A* to C, compared with 75% of boys.

And according to this year's university application figures, the difference in application rates between men and women across the UK is the widest on record.

In England, young women are 36% more likely to apply than young men.

The gender gap in applications is also at its greatest ever in Scotland and Wales, while in Northern Ireland there is the largest gap since 2009.

'Eclipsed'

Mary Curnock Cook, chief executive of the University and College Admissions Service, is so concerned for the future of boys that she wants to see a concerted national effort to tackle the issue.

If current trends continue, she says, within a decade the gap between rich and poor at university entrance will be "eclipsed by the gap between males and females".

Furthermore, she predicts: "If this differential growth carries on unchecked, then girls born this year will be 75% more likely to go to university than their male peers."

So what is at the root of this gap?

Are girls simply academically better these days, and boys less ambitious?

Or is something more complicated happening?

By the time teenagers get to sixth form, girls are already significantly outnumbering boys, let alone outperforming them.

That is a result of their better results at GCSEs.

Some 55% of pupils taking A-level standard qualifications were female in 2015, compared to 45% of boys.

So before they sit a single exam, there are potentially more girls than boys who are likely to go to university.

'Waste of time?'

Once the exams are done and dusted, they tend to get better results.

The average A-level grade for a girl is C+ compared to C for a boy.

But the differences between boys and girls start much earlier on.

According to a University of Bristol study, boys are nearly twice as likely as girls to have fallen behind by the time they start school.

The research found 80,000 boys in England started in a reception class struggling to speak a full sentence or follow instructions and, worryingly, many of these children will never catch up.

Add to this the fact that primary schools tend to be dominated by female teachers, and mothers helping out, and the jigsaw of male underachievement does not look quite so puzzling.

According to research into boys' underachievement for the Higher Education Policy Institute, girls and boys often have different cultural attitudes towards school work.

The report by its director Nick Hillman, quoting OECD research, says: "Boys are eight percentage points more likely than girls to regard school as a waste of time."

And across OECD countries boys tend to spend over one hour less per week on homework than girls, he adds.

Boys are more likely to play computer games and less likely to read outside of school, he says in his paper.

Boys are said to play more computer games than girls

This sense that boys are not so keen to apply themselves academically is backed up by the former head teacher of Sydney Russell School in Dagenham, Roger Leighton.

"There is a touch of boys having a greater tendency to think they can get away with minimum work and wanting to spend their time doing other 'more interesting things'," he says.

"Girls, on the other hand, tend to understand the need to knuckle down earlier on - they take a longer view."

There are some other changes in the nature of universities which have led to the dominance of women on campus.

The conversion of the old polytechnics to universities in the 1990s brought a huge swathe of female students into the university fold.

And as Mr Hillman remarks: "Skilled careers traditionally chosen by women, such as nursing and teaching, did not demand full degrees in the past."

"When this changed, the number of women in higher education increased dramatically," he adds.

Once subjects linked to medicine and education are discounted, the disparity in the total number of male and female higher education students drops from around 281,000 to just 34,000.

However, men are not completely on the back foot in higher education.

They are still outperforming women in some of the most prestigious areas - such as entry to the toughest universities and toughest courses.

- Published18 August 2016

- Published17 August 2017