Did grammar schools help social mobility?

- Published

Theresa May has highlighted that "selection by house price" was also unfair

The argument for expanding grammar schools in England makes two big claims - that it will improve choice for families and support social mobility.

The arguments against grammars are the precise opposite of this - that expanding grammars will leave most families with less chance of a good school and drive social division.

But what is the evidence?

Academics researching education are sceptical, to put it mildly, that more selection has ever widened social mobility.

Stephen Gorard, professor of education at the University of Durham, says "any policymaker who cares about educational effectiveness or social justice" should not "promote or condone" selection by ability.

"There is repeated evidence that any appearance of advantage for those attending selective schools is outweighed by the disadvantage for those who do not," he says.

Will grammar schools help or hinder the chances of poorer pupils?

"More children lose out than gain, and the attainment gaps between highest and lowest and between richest and poorest are larger."

But could grammars break the link between family background and how well children achieve at school?

Could they help bright working class youngsters get into the type of schools that otherwise would be unobtainable?

Dr John Goldthorpe, of Oxford University, says long-term studies carried out between the 1940s and 1970s provided an unintended "natural experiment" into whether grammars made any positive difference to social mobility.

For the cohort of children born in 1958, their school years overlapped with the change from grammars to comprehensives.

Graham Brady says grammars are a challenge to the dominance of private schools

And the study was able to compare children who went to school in areas that still had the 11-plus test and those who were taught in comprehensive schools.

Dr Goldthorpe says it showed that neither system made any difference to social mobility or altered this pernicious link between education and class.

The existence and the disappearance of grammars did not change the relentless impact of family background on school achievement, says Dr Goldthorpe.

He says the rather uncomfortable truth for politicians is that their policy choices in education make much less difference than they might like to think.

Dr Goldthorpe says that education systems, however they are configured, are much more likely to mirror inequalities than to challenge them.

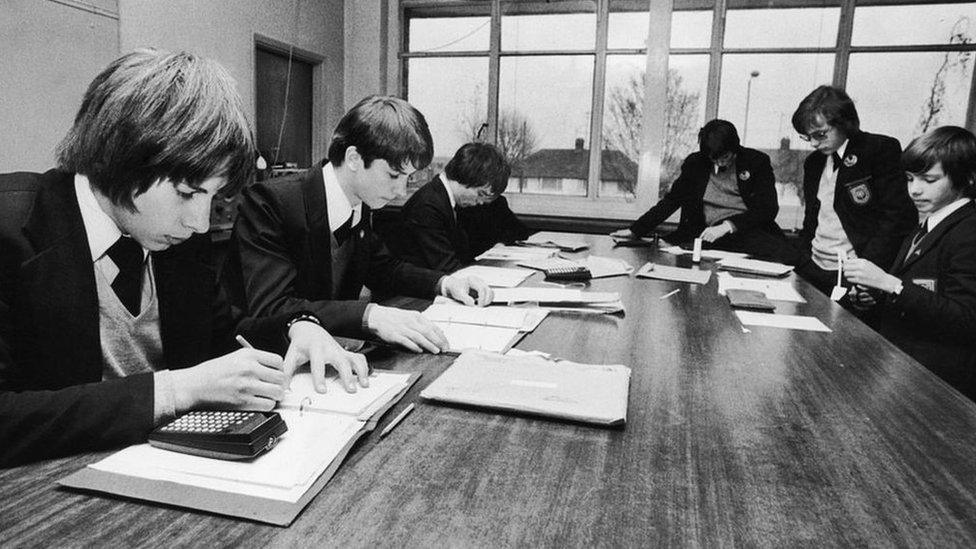

Researchers were able to track what happened as the grammar system was closed

It is also worth considering this from an international perspective.

A key reason that school systems such as Shanghai in China are at the top of international rankings is that they are structured to expect all pupils to reach a certain threshold of achievement.

They put the best teachers into the worst schools to make sure that almost everyone gets across the finishing line.

England's school system historically has always been more like the Grand National, with large numbers of starters and many fewer expected to still be there at the end - and only a handful in the winner's enclosure.

What is remembered as "social mobility" for bright, working class children who did well from the grammar school system was also a form of competition.

Those that lost, and ended up in secondary moderns, faced "pretty dreadful" chances of reaching their potential, says Dr Goldthorpe.

Education Secretary Justine Greening has said there will be no wholesale return to selection

And, as Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw has said repeatedly, opening a grammar school for the top quarter means opening three secondary moderns for the rest.

The academy project - that was so central to education under David Cameron's administration - must now seem to have lost some momentum.

Perhaps this would not matter if there was a level playing field on entry for grammars - but successive studies have shown that poorer pupils are generally much less likely to get places in grammar schools.

According to the Sutton Trust, only 3% of entrants to grammar schools are entitled to free school meals, when in selective areas the average proportion of free school meal pupils is 18%.

But, as the Prime Minister Theresa May has said, anyone criticising the lack of social mobility of grammars also has to face up to the inequalities in other ways of admitting pupils.

It is another difficult truth that the most common way of deciding school places - distance from school - has also been identified by researchers as a major cause of social division in education.

Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw says re-opening grammars would be a retrograde step

A major study by Cambridge University, Bristol University and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, said this approach drove inequality between rich and poor - and meant the most sought-after places were taken by those who could afford the inflated house prices.

Graham Brady, Conservative MP and prominent grammar supporter, also points out the bigger picture of educational privilege.

He looks to grammars as offering a challenge to the even more unfair dominance of private schools.

"They provide opportunities for huge numbers of people of modest means who couldn't access fee-paying schools," says Mr Brady.

"The 7% who go to fee paying schools now take up around half the places at Oxbridge, dominate the law, the media, the senior civil service - and won 30% of our Olympic medals."

And he points to research from the Sutton Trust showing how popular comprehensives in affluent areas have themselves become "socially exclusive", with "selection by house price".

In contrast, Mr Brady evokes that powerful folk memory of grammar schools offering hard-working, bright children from non-wealthy homes an education that was as good as anything in a private school.

It also taps into another key feature of England's school system - the importance of status. And grammars, with their ethos and sense of tradition, have never been short of applications.

It raises other questions that parents might not always want to talk about out loud.

Do you want fair for everyone or something better for yourself?

Do you want personal upward mobility more than social mobility for others? And doesn't every parent want to have the best for their children?

And why can't excellence and ambition be unpicked from ideas of elitism and exclusivity?

The grammar debate will go on - because arguments about education are about instincts and ambitions as much as evidence.