Detentions - a nightmare for everyone?

- Published

School gets tougher for everyone as the end of term draws nearer

It is late November, the summer holidays are ancient history, September resolutions about behaviour and homework are forgotten, everyone is tired, behaviour has slumped and detentions are hitting an end-of-term peak.

Detentions are a fixture of school life, but do they really improve behaviour?

Here are some of your stories.

Misbehaviour masterclass

"We used to rip up work and make it 'snow' out the window, ignore teachers and keep chatting, put tacks on their seats, use it as choir practice, paint our nails, cornrow hair," says one former London comprehensive pupil, now a junior doctor.

Some pupils collect detentions like trophies.

"We were the outlaws, the desperadoes, members of a bad-but-fun gang, playing cat and mouse with authority," says a former private school pupil.

Another, remembering detentions in the 1980s, says: "Collapsing of tables was a favourite for us.

"We had real ink pots and trestle tables, so all you had to do was kick the support on the table and the whole thing would collapse and then ink all over the floor.

"'Oops, sorry, don't know how that happened.'"

A former Hertfordshire comprehensive pupil, now in her 20s, says: "We had so many, it turned into our after school club.

"One of the teachers gave up in the end. And the next time we were in, she put a film on.

"I think it was Romeo and Juliet, the Leonardo [DiCaprio] one.

"If we weren't in trouble, we would wait outside for the ones that were.

"One time I spent 100 minutes in a cupboard in the classroom with a friend.

"We weren't meant to be there, but it was cold outside and it seemed like a fun thing to do whilst we were waiting.

"They weren't a deterrent at all."

What do you think? Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external

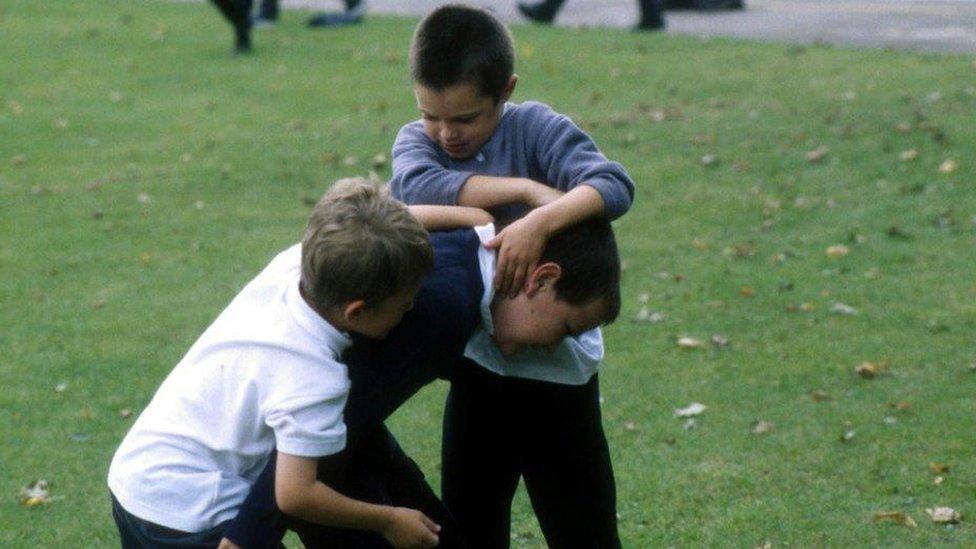

Detentions can become an exercise in defiance

Forgetting to turn up

Many teachers say detentions should take place on the day of the offence, external, when pupils will understand better why they are being punished.

Same-day sanctions also improve pupils' chances of remembering the detention at all.

In some schools, even if the original offence is small, such as wearing the wrong shoes, not turning up to detention can result in as much punishment as for someone who started a fight.

"Not a fair system," says one recent school leaver from Hillingdon.

Fighting is definitely bad behaviour, but forgetting a detention can get you into almost as much trouble

Confused parents

Schools in England do not need permission, external from parents to impose detentions, and in most cases they are not even required to inform them.

So the first they know is when their child is late home, and even then they might not find out why.

"Every other Monday over almost my entire 13th year, I told our parents I was at chess club, which worked well until they found out from talking to the parents of a fellow detainee who let the cat out of the bag," says one former London pupil.

Another says: "My mum was too busy to even know I had it half the time.

"So I didn't get into trouble at home."

All for one

You should have said it was chess club

Whole-class detentions are particularly controversial with better behaved class members.

"So all 30 of us had to stay behind for a couple of obnoxious people. This is so unfair. How does this help anyone?" asks one school-leaver.

"Surely, in an ideal world teachers should ask the class for their opinions on the problem and work with them to find a fair and creative solution. How hard can it be?"

Socially useful

Some schools make pupils on detention engage in socially useful activities such as litter picking the playground, which can be quite satisfying.

And detention can be a chance to get all your homework done in one go, rather than having it last all week.

But this approach can backfire too.

"One of the chores we were given to do sometimes in detention was to clean board-rubbers, which was basically a licence to get everything and everyone in sight covered in chalk dust," says a former pupil from Cheshire.

Detention for teachers

A pile of marking seems attractive by comparison

With lesson planning, marking and a dozen more extracurricular jobs at the end of the day, supervising an after-school detention is not fun for teachers.

"Deeply dull," says one.

At some schools, pupils in detention must write an essay on "what action they did wrong and what choices they have in the future when in that position".

This approach can "often work", say some teachers, but others disagree

"I loathed the idea of making children write for a punishment and taking away their valuable time when they could be running around in the sun or staring at ants in the grass," says one recent retiree, who never gave a detention in 36 years of teaching.

Even supporters of detention say it is futile without proper communication between pupil and teacher.

"It shouldn't be about getting the kid to say sorry," says one London teacher.

Basic conflict resolution techniques can help, she adds, "where both sides get to reflect on the situation from the other's point of view".

Pupils need to think about how their behaviour can make teaching very difficult, while teachers could consider whether, in their drive to deliver the curriculum, they might be overlooking pupils' underlying learning difficulties, she says

But others fear that in today's results-focused classrooms, "teachers too often lack the time and the skills" for this kind of approach.