Bletchley Park: 'Codebreakers school' planned for site

- Published

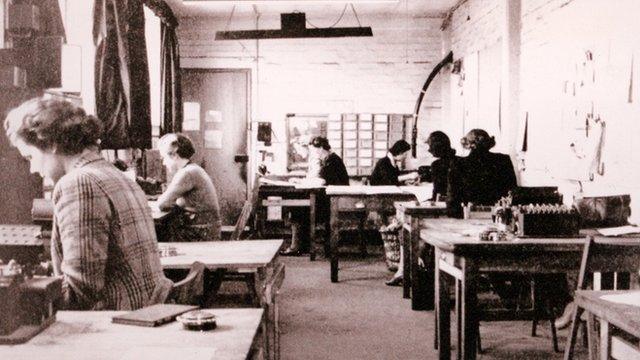

Staff working on decoding projects at Bletchley in 1940

Bletchley Park, the site of secret code-deciphering projects during World War Two, could become the centre for a new generation of codemakers and codebreakers.

There are plans for a training college to teach cybersecurity skills to 16-19 year olds at the Buckinghamshire site.

Former home secretary Lord Reid said it had become vital to build up the "talent pool" for cyber-defence.

The college, in a wartime building at Bletchley, is intended to open in 2018.

Developed by a not-for-profit group from the cybersecurity industry, it would open as a boarding college, with around 10% of places for day students.

The National College of Cybersecurity would be free to all students, who would be selected as "gifted and talented".

The BBC understands that candidates would not need to meet specific academic qualifications, but would be selected through aptitude tests, or on the basis of exceptional technology skills - such as self-taught coders or students who dabble in making their own websites.

The students would work towards a potential variety of qualifications including A levels or Extended Project Qualification (EPQs). Around 40% of the curriculum would be devoted to cybersecurity - with extra focus on maths, physics, computer science or economics.

Bletchley Park was a base for wartime efforts to decipher encrypted messages

There have been repeated warnings about the lack of a skilled workforce for cybersecurity in the UK, despite a rising number of sophisticated cyber-attacks.

A spokesperson for the GCHQ intelligence agency welcomed such "initiatives that promote and develop skills in cybersecurity".

"The concept of a sixth-form college is interesting, especially if it can provide a pathway for talented students from schools that are not able to provide the support they need," the spokesperson added.

The project plans to use G-Block, built in 1943, on the Bletchley Park site as the base for the college, with a £5m restoration project for the building.

Bletchley Park: Britain's best kept secret

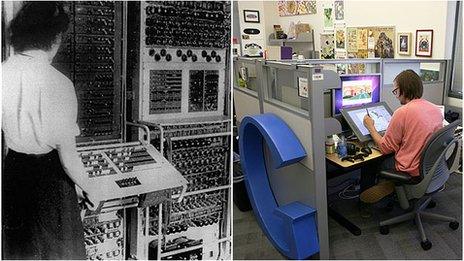

The wartime team at Bletchley Park created the world's first computer

Bletchley House was Britain's best kept secret for decades. No one was allowed to talk about the work that was carried out there during World War Two - and it was not until a veteran code-breaker spilled the beans in 1974 that its existence became known.

During the war, it housed the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) which worked on cracking the military codes that secured German, Japanese and other enemy nation's communications.

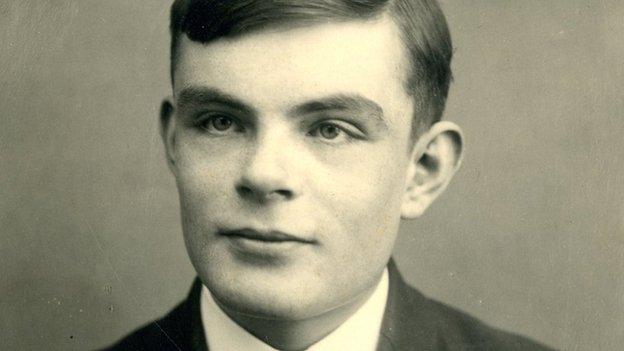

The Bletchley Park wartime team included code-breaker Alan Turing

The work of the wartime team, which included the computer scientist Alan Turing, heralded the dawn of the information age - creating the world's first computer, Colossus - and was famed for breaking the German Enigma encryption system.

After the war, some of the staff stayed on in a new organisation, Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ).

Now one of three UK intelligence and security agencies, along with MI5 and MI6, GCHQ works to keep the UK safe.

British Intelligence moved GCHQ to a new site in Cheltenham in 1987

GCHQ credits its "particularly strong" relationship with its US equivalent, the National Security Agency, to the collaboration it began at Bletchley Park and agreements it signed at the end of World War Two.

Bletchley Park was decommissioned in 1987 after a 50 year association with British Intelligence, which relocated GCHQ to Cheltenham. There are also smaller sites in Cornwall, North Yorkshire and Manchester.

In 1991, moves to demolish the site sparked an eight year battle to save Bletchley Park and keep its wartime story alive. The Bletchley Park Trust is now working on a 10-year plan to transform the site into a world-class museum and education centre.

The plan for training a new generation of codebreakers at Bletchley comes from a group called Qufaro, set up by cybersecurity representatives, including from Cyber Security Challenge UK, The National Museum of Computing and BT Security.

Funding and development comes from Qufaro in collaboration with the Cyber Security Challenge UK - a government and industry backed-competition that seeks people with the the skills needed to help the UK beat back cyber criminals, hacktivists and terrorists. It also has the backing of City and Guilds, which provides vocational qualifications.

Alastair MacWilson, of the Institute of Information Security Professionals and chair of Qufaro, says cyber-education at the moment is "disconnected and incomplete, putting us at risk of losing a whole generation of critical talent".

He says that the Qufaro project would help to provide a more "unified" approach to try to fill the gaps in training.

Block G at Bletchley, which could be restored to house the cybersecurity school

Margaret Sale, founding member of the National Museum of Computing, said setting up a college would help to "reactivate" the site as a "major active contributor to our national security".

Lord Reid, who chairs the Institute for Security and Resilience Studies at University College London, said cyber-activity "now reaches into every aspect of our lives, as individuals and as a nation".

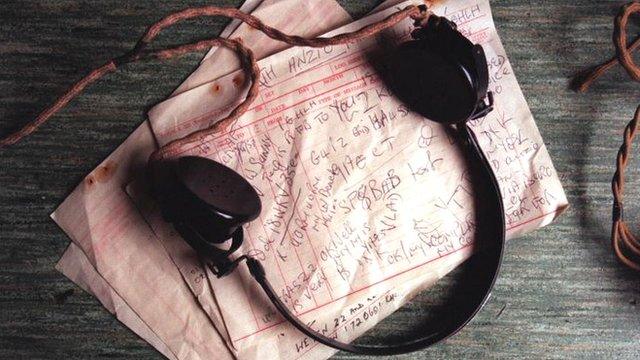

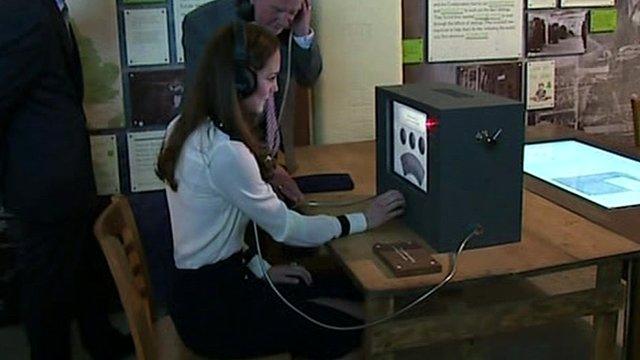

Wartime decoding equipment used at Bletchley Park

But he said there was a challenge in "developing a sustainable flow of skilled professionals for security, growth and cyber-innovation.

"Existing initiatives cannot close the skills gap alone so it is vital that we keep looking for new ways to build our talent pool," he stressed.

He said the plans for a National College of Cyber Security could "harness the legacy of this historic location to inspire the next generation".

- Published1 November 2016

- Published13 September 2016

- Published20 October 2016

- Published18 June 2014

- Published18 June 2014

- Published16 November 2011