Pisa tests: Singapore top in global education rankings

- Published

Singapore has been ranked as having the highest-achieving schools

Singapore has the highest achieving students in international education rankings, with its teenagers coming top in tests in maths, reading and science.

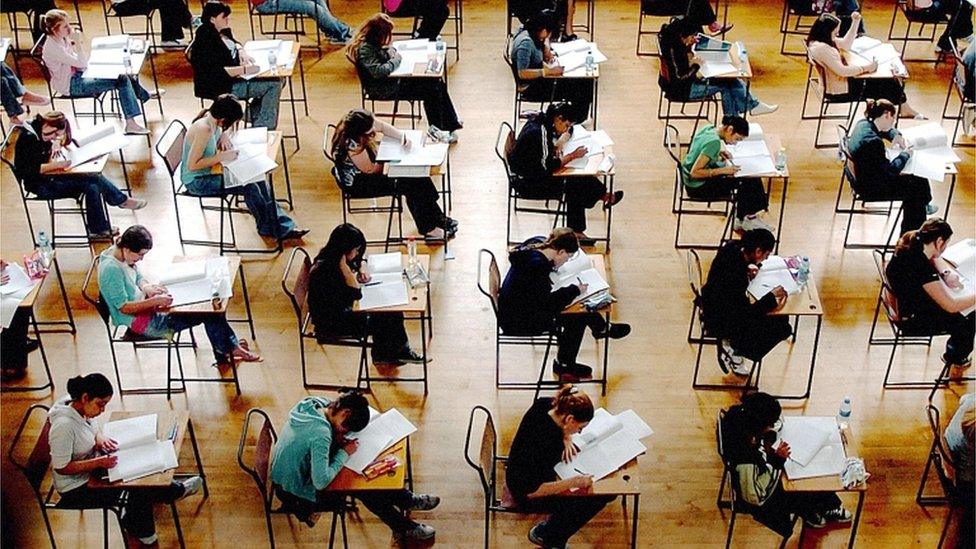

The influential Pisa rankings, run by the OECD, are based on tests taken by 15-year-olds in more than 70 countries.

The UK remains a middle-ranking performer - behind countries such as Japan, Estonia, Finland and Vietnam.

OECD education director Andreas Schleicher said Singapore was "not only doing well, but getting further ahead".

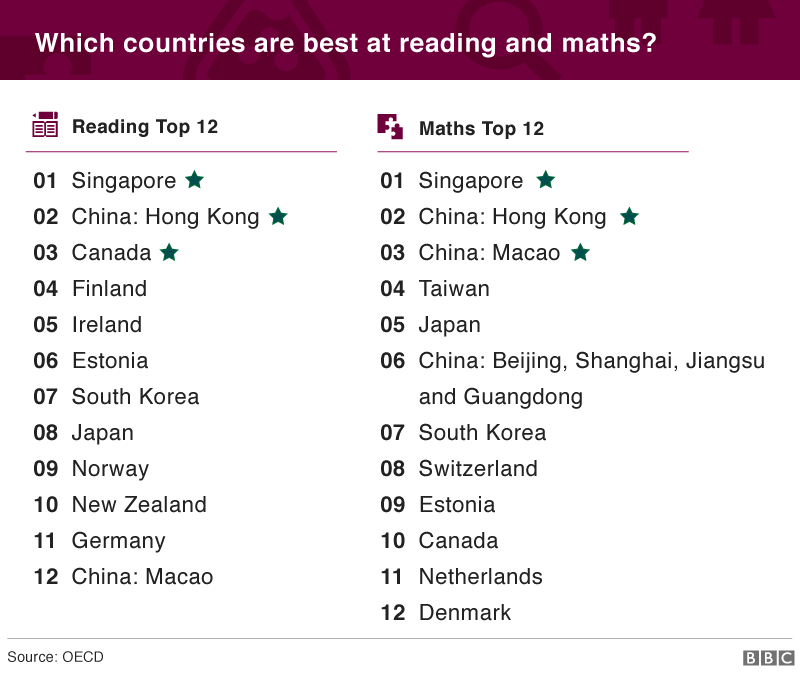

Singapore, named as the top rated country for maths and science in another ranking last week, is in first place in all the Pisa test subjects, ahead of school systems across Asia, Europe, Australasia and North and South America.

What is Pisa? In three sentences

The Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) provides education rankings based on international tests taken by 15-year-olds in maths, reading and science.

The tests, run by the OECD and taken every three years, have become increasingly influential on politicians who see their countries and their policies being measured against these global school league tables.

Asian countries continue to dominate, with Singapore rated as best, replacing Shanghai, which is now part of a combined entry for China.

Singapore has replaced Shanghai as the previous top-ranked education system - with Shanghai no longer appearing as a separate entry in these school rankings.

There had been debate over whether Shanghai was representative of school standards across China - and this year, for the first time, Shanghai is included in a wider figure for China, based on schools in four provinces.

This combined Chinese ranking is in the top 10 for maths and science, but does not make the top 20 for reading.

Hong Kong and Macao also appear among the high-achieving education systems.

The US has again failed to make progress.

"We're losing ground - a troubling prospect when, in today's knowledge-based economy, the best jobs can go anywhere in the world,'' said the US Education Secretary, John King.

Asian countries on top

Asian education systems dominate the upper reaches of the these results tables - accounting for the top seven places for maths, with Singapore followed by Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Japan, China and South Korea.

The UK's test results remain behind the top-performing Asian education systems

Finland, Estonia, Canada and Ireland are the only non-Asian nations to get into any of the top five rankings across all three subjects.

Mr Schleicher said that Asian countries such as Singapore managed to achieve excellence without wide differences between children from wealthy and disadvantaged families.

He described Vietnam's progress as "quite remarkable", coming ahead of Germany and Switzerland in science - and ahead of the US in science and maths.

Andreas Schleicher says Singapore has high results without a big gap between rich and poor

Among South American countries, Mr Schleicher highlighted the improvements in Peru and Colombia.

But the UK has failed to make any substantial improvement - despite education ministers in England making the Pisa rankings an important measurement of progress.

In maths, the UK is ranked 27th, slipping down a place from three years ago, the lowest since it began participating in the Pisa tests in 2000

In reading, the UK is ranked 22nd, up from 23rd, having fallen out of the top 20 in 2006

The UK's most successful subject is science, up from 21st to 15th place - the highest placing since 2006, although the test score has declined

Within the UK, Wales had the lowest results at every subject.

Education Secretary Kirsty Williams said: "We can all agree we are not yet where we want to be."

But she said that "hard work is underway" to make improvements in Wales - and that it was important to "stay the course".

Scotland trails behind England and Northern Ireland - recording its worst results in these Pisa rankings.

Deputy First Minister John Swinney said the "results underline the case for radical reform of Scotland's education system".

England had the strongest results in the UK, but compared with previous years, Mr Schleicher said "performance hasn't moved at all".

The OECD education chief highlighted concerns about the impact of teacher shortages - saying that an education system could never exceed the quality of its teachers.

"There is clearly a perceived shortage," he said, warning that head teachers saw a teacher shortage as "a major bottleneck" to raising standards.

So why is Singapore so successful at education?

Singapore only became an independent country in 1965.

And while in the UK the Beatles were singing We Can Work It Out, in Singapore they were really having to work it out, as this new nation had a poor, unskilled, mostly illiterate workforce.

Singapore made a priority of recruiting top graduates into teaching

The small Asian country focused relentlessly on education as a way of developing its economy and raising living standards.

And from being among the world's poorest, with a mix of ethnicities, religions and languages, Singapore has overtaken the wealthiest countries in Europe, North America and Asia to become the number one in education.

Prof Sing Kong Lee, vice-president of Nanyang Technological University, which houses Singapore's National Institute of Education, said a key factor had been the standard of teaching.

"Singapore invested heavily in a quality teaching force - to raise up the prestige and status of teaching and to attract the best graduates," said Prof Lee.

The country recruits its teachers from the top 5% of graduates in a system that is highly centralised.

All teachers are trained at the National Institute of Education, and Prof Lee said this single route ensured quality control and that all new teachers could "confidently go through to the classroom".

This had to be a consistent, long-term approach, sustained over decades, said Prof Lee.

Education was an "eco-system", he said, and "you can't change one part in isolation".

- Published30 November 2016

- Published5 December 2016

- Published4 December 2016