How schools promote pupils' mental wellbeing

- Published

Teachers are often the first to notice changes in the wellbeing of their pupils, say heads

Schools have long been are at the front line when it comes to identifying and helping children with mental heath problems.

But some heads wonder how much longer they can continue to provide in-school counselling and mentoring as budgets flatline and costs rise.

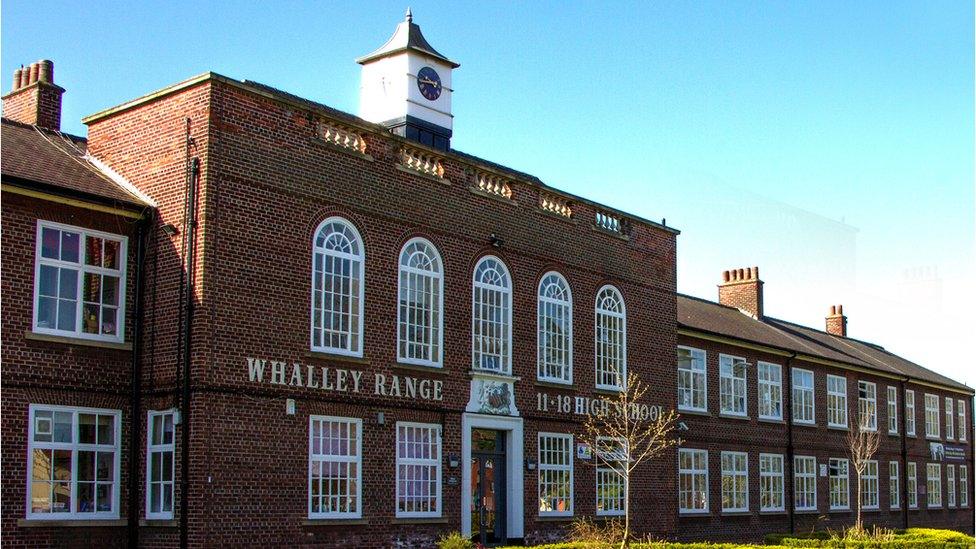

At Whalley Range High School in inner-city Manchester, students' mental wellbeing is a priority.

"There is a lot of stress," executive head teacher, Patsy Kane, told the BBC.

There is a waiting list for the school's counselling service, funded from its general budget, and two specially trained support staff run a child protection service.

Teaching staff were "vigilant", keeping an eye out for pupils showing raised levels of stress and anger, said Ms Kane.

Growing demand

Each year group at the 1,500 strong girls' secondary has its own pastoral manager whose duties include ongoing assessment of pupils' mental health.

There is also a school nurse and a school counsellor available four or five days each week, all paid for from the school's overall budget.

The academy trust that runs Whalley Range also includes Levenshulme High School for girls and East Manchester Academy, which is mixed.

They serve some of the most deprived and culturally diverse wards in the city and all have a strong focus on pupils' mental health.

The real difficulties come when pupils' problems go beyond the capacity of the professionals in the school, according to Ms Kane.

"Local services are just overwhelmed," she said.

"These are very challenging times."

Ms Kane said the schools often had to advise parents to take children with suicidal thoughts straight to accident and emergency "as this can be the only way to get support quickly".

And one pupil "in extreme need" had been sent to a hospital in the north-east of England "hundreds of miles away as there was not a single adolescent mental health bed available in this region".

"If there isn't a bed, a child's life could be at risk," she said

But being treated so far from home was even more disorientating for distressed teenagers.

Whalley Range High School - where pupils' mental wellbeing is a priority

Demand for in-school counselling was growing and pupils were offered the service "for as long as they need it," said Ms Kane.

But changes to the way school budgets were calculated in England meant that many inner city schools, including in Manchester, faced cuts.

"I don't know how much longer we are going to be able to protect counselling," she said.

Under government plans, announced on Monday, all secondary schools will be offered mental-health first-aid, external training.

The plans also include a pledge that by 2021 no child will be sent away from their local area for treatment.

But with budget pressure on existing services already apparent, head teachers' leaders are anxious to know how the plans will be funded.

"This is a highly complex area," said Malcolm Trobe, interim general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, which represents secondary heads.

"Many schools already provide their own support on site, and do a very good job despite limited resources, but they often face serious difficulties in referring young people to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

"There is simply not enough provision - and families face excessively long waiting times," said Mr Trobe.

Exam stress

According to the National Association of Head Teachers, about three-quarters of schools already lack the funds to provide good enough mental health care for pupils.

"Rising demand, growing complexity and tight budgets are getting in the way of helping the children who need it most," said NAHT general secretary Russell Hobby.

"Moves to make schools more accountable for the mental health of their pupils must first be accompanied by sufficient school funding and training for staff and should focus only on those areas where schools can act, including promotion of good mental health, identification and signposting or referrals to the appropriate services," he added.

For Ms Kane, the emphasis is on making the schools she runs "safe and welcoming places".

Counselling and other forms of psychological support were more important than ever as changes to the exam system "are creating more stress", she said.

"There is a lot of memorising required and less course work."

The school holds assemblies for candidates, on how to revise and relax, and mindfulness training.

And there are lessons in small groups for some of the more vulnerable pupils.

There is also an emphasis on sport, and the school encourages volunteering.

"You feel better if you help someone else," said Ms Kane.

"We want students to learn strategies for life. It's not just about protecting them."

- Published9 January 2017