'We were nine round the table, now I am the only one'

- Published

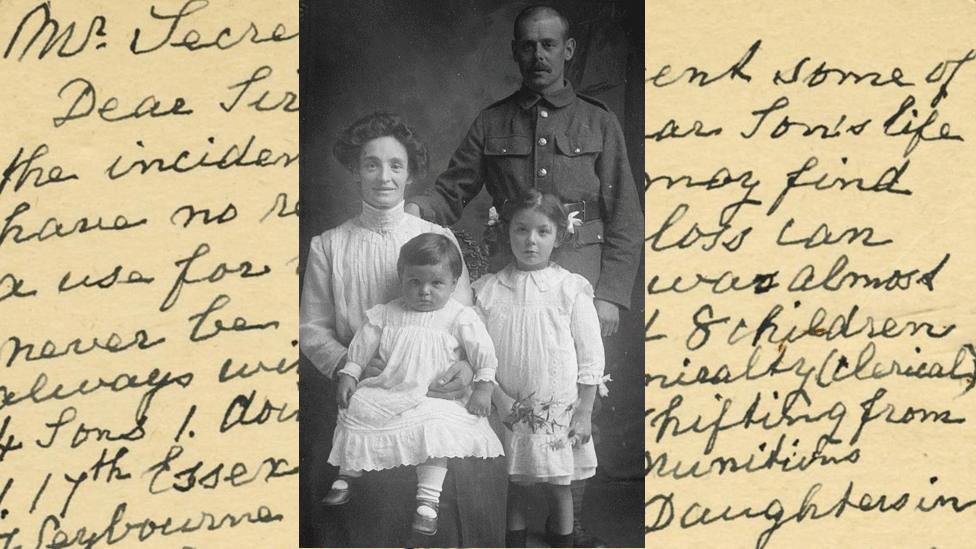

Clarence Chessum survived only a few weeks on the front and left behind two children

If you think of the Imperial War Museum as a place full of tanks, interactive displays and a Spitfire hanging above an exhibition hall - its beginnings were very different. As the museum marks its centenary, it is making public the very personal mementoes in its first collection.

"Dear sir, I have sent some of the incidents of my dear son's life. Have no relics. You may find a use for them. His loss can never be made up. Was almost always with us.

"We were nine round the table, now I am only one.

"Excuse me troubling you with all this but it's life as it is."

The Imperial War Museum is marking its centenary by showcasing some early exhibits

The letter was from Sarah Chessum, a mother whose son had been killed in the trenches of the World War One in March 1917.

She was responding to a call from a new type of museum being created as a memorial for a war still being fought.

That museum, now the Imperial War Museum, is celebrating its centenary by making some of these earliest items public for the first time.

The museum began by asking for personal keepsakes of soldiers who had died - such as last letters, photographs or personal items - with the request printed on ration books.

It was as much a memorial shrine as a museum, with bereaved relatives such as Sarah Chessum hand-delivering or posting these poignant items.

Charlotte Czyzyk, a World War One historian at the museum, says even a century later these letters are "heartbreaking".

Sarah's son, Clarence, had left for France in January 1917, and barely eight weeks later he was dead.

He was aged 37, a bookbinder from north London, a slight figure of 5ft 3in, who had left two children.

Joy Hunter met Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in 1945 and gathered pieces of Hitler's desk

Another letter came from Gilbert Salisbury, a Canadian soldier who survived the War, but whose wife had died in 1918 from Spanish flu.

"The end of the War means for the world at large peace and happiness, where it means for me desolation and sorrow," he wrote, in his contribution to the museum.

Thousands of families sent in pictures and letters - stored at the museum's first location, in Crystal Palace, in south London.

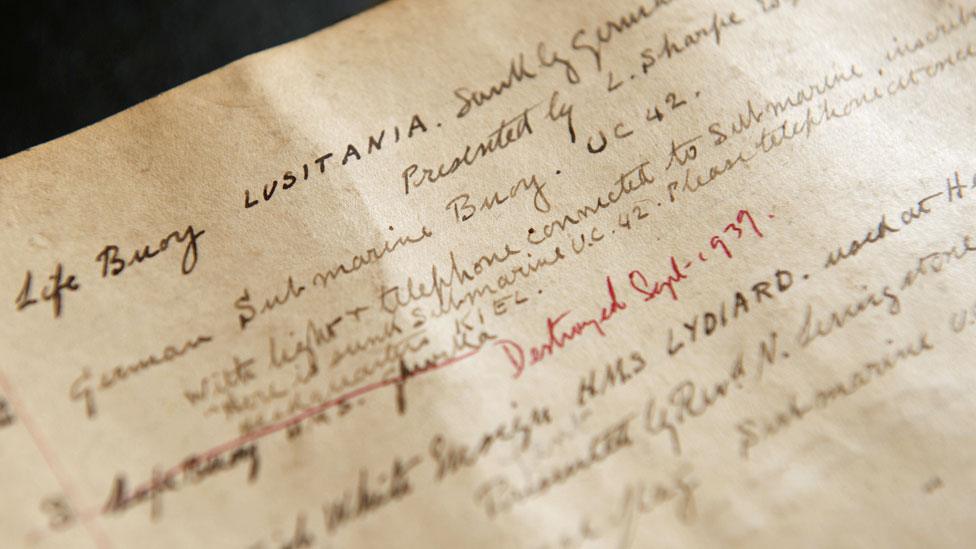

Weapons and equipment were also collected - with the very first acquisition a lifebuoy from the Lusitania, a liner sunk by a German submarine in 1915.

The idea of creating a museum in 1917 reflected the need to respond to the unprecedented scale of the conflict.

"There was still no end in sight for the War," says Ms Czyzyk.

While the War was still being fought, items were gathered from the front

The previous year had seen the monumental battles of the Somme on land and Jutland at sea.

There was conscription, and more women were going into work. The War was touching every part of society.

"This was a type of war that had never been seen before," says Ms Czyzyk.

The war museum would be a form of memorial, and its building blocks would be the stories and pictures of ordinary families caught up in these extraordinary events.

"They're saying, 'This was my boy, I'd like you to have this photograph to help remember him.' That would have been a really big thing for that family," says Ms Czyzyk.

A lifebuoy from the Lusitania was an early acquisition

Millions visited the museum in Crystal Palace and then in South Kensington. And then in 1936, the museum moved to its current home in Lambeth - in a building previously occupied by the Bethlem Hospital for the mentally ill.

At the outbreak of the World War Two, the museum's collection had its own call-up, with some "historic' weapons on display pressed back into action.

The modern Imperial War Museum group includes one of the wartime nerve centres - the Cabinet War Rooms, where Winston Churchill worked underground while London faced Nazi air raids.

The museum's collection of war objects was headed by a lifebuoy from the Lusitania

Joy Hunter worked as a secretary in this underground communications centre - and as well as the fog of war, she had to contend with the fog of Churchill's cigars.

Now aged 91, she remembers the strange subterranean world, where an evening could end with the staff watching a film with Churchill, in his pyjamas and drinking whisky, in a makeshift cinema.

"We found him very affable to civilians - other people will tell you different stories - but he was always very pleasant to us and would say stop and say good morning or whatever," she says.

"I've a feeling that it was a relief for him to have civilians, perhaps it made him feel more normal."

Millions of visitors came to see the war relics put on show in Crystal Palace

She remembers how difficult it was to keep the prime minister underground during air raids, when he wanted to go up on to the rooftops to watch.

Mrs Hunter says it is hard for people now to understand how they worked - "in total war and total secrecy and total silence".

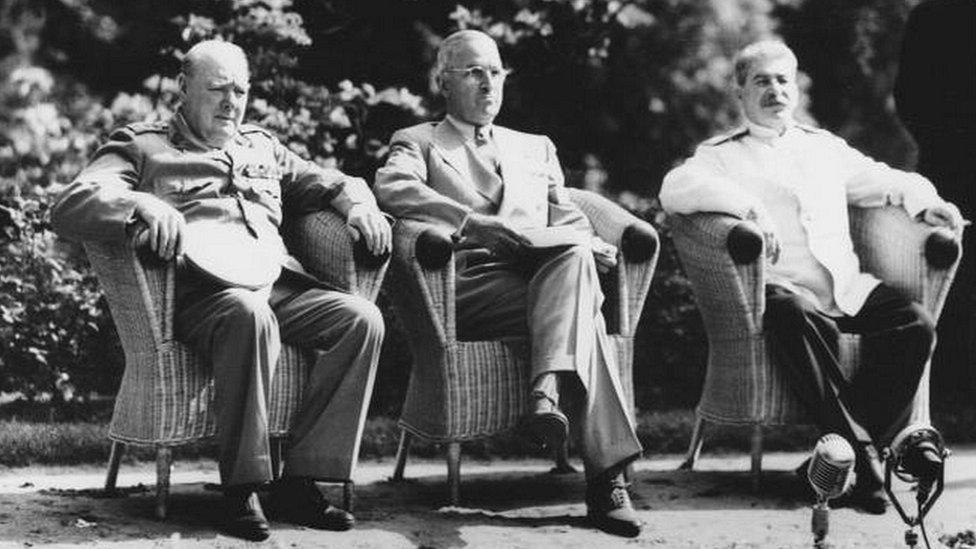

Mrs Hunter typed the battle orders for D-Day and on the defeat of the Nazis, she flew to the Potsdam conference where Churchill met Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and US president Harry Truman.

She got to meet the Soviet leader in person.

"I kept very quiet about shaking Stalin's hand because I thought people might think it wasn't quite the thing to have done," she says.

The museum collected war equipment - some of which was put back into action in World War Two

"I can say it now without blushing too much."

But the appalling conditions in Berlin left her "stunned".

The city was filled with the "stench of death", she says, with the population looking like "zombies" and begging for food.

She had seen the damage from air raids on London, but Berlin was much worse.

She went to the victory parade in the city, but took no pleasure from it.

"I felt very awkward. I didn't feel very victorious at all. I just thought this is horrendous," she says.

Joy Hunter was at the Potsdam conference, where Churchill met Stalin and Truman

Mrs Hunter brought home part of the shattered city - in pieces of marble from Hitler's desk, which she had found in the ruins of the Nazi leader's chancellery.

Her own memories are now the stuff of museum displays - but she says anyone looking back should not glorify war.

"Of course, we should remember, but you can't live in the past," she says.

"We should remember and take it with us and make sure that it doesn't happen again. But who knows?"