Most teenagers happy with life, study finds

- Published

- comments

Most 15-year-olds report being happy with their lives, an international study of students' well-being suggests.

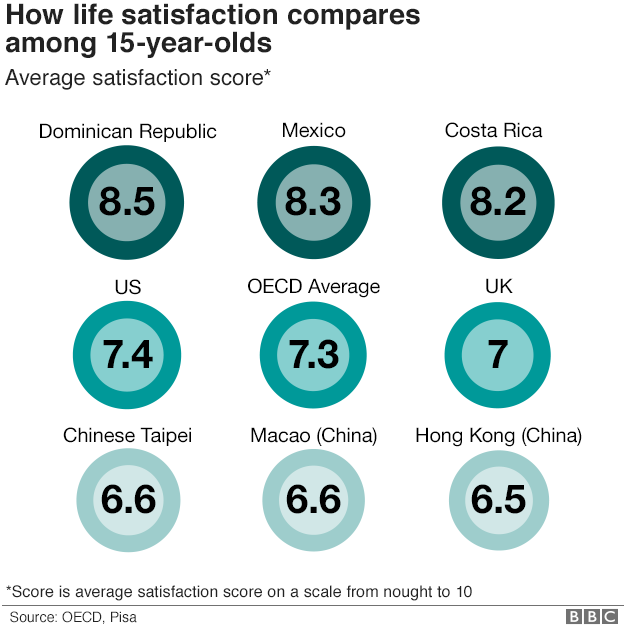

The report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found an average satisfaction score of 7.3 on a scale from nought to 10.

UK teenagers had a below average satisfaction score of seven.

But anxiety about exams and bullying remains a problem for many young people. And heavy internet use leaves many feeling lonely and less satisfied.

The findings are based on a survey of 540,000 students internationally who also completed the OECD Pisa tests in science, mathematics and reading in 2015.

The study reveals large variations in life satisfaction out of 48 OECD countries and partner nations.

The highest levels of satisfaction were found in the Dominican Republic (8.5), Mexico (8.3) and Costa Rica (8.2), while the Asian countries or economies of Korea (6.4), Hong Kong (6.5), Macau (6.6) and Taiwan (6.6) recorded low levels of satisfaction.

The UK took 38th place for life satisfaction, behind countries such as Russia (7.8), Bulgaria (7.4) and Estonia (7.5).

The study found girls and disadvantaged students were less likely than boys and advantaged students to report high levels of life satisfaction.

UK 15-year-olds

life-satisfaction score of seven on a scale of nought to 10, below the United States (7.4), France (7.6), Germany (7.4) and Ireland (7.3)

72% said they felt very anxious before a test - even when they were well prepared

almost one in four (24%) said they were victims of one act of bullying at least a few times a month

some 15% said they were made fun of by others and 5% that they were hit or pushed at least a few times a month

but teenagers perceived a high level of parental support, with 93% saying their parents encouraged them to be confident and 94% saying parents were interested in their school activities

Despite reasonably high average levels of satisfaction, bullying was a significant problem for many youngsters, with a large proportion saying they had been victims.

On average across OECD countries, about 11% of teenagers said they were frequently mocked, 7% were "left out of things" and 8% were the subject of hurtful rumours.

Around 4% of students - approximately one child per class - reported that they were hit or pushed at least a few times per month.

But the OECD research found less bullying in schools where students had positive relationships with their teachers.

Exam stress was also a problem, with 59% of students saying they often worried that taking a test would be difficult and 66% saying they worried about getting poor grades.

Across OECD countries, about 55% of students said they were very anxious before a test, even if they were well prepared for it.

Girls had a tendency to worry more than boys, with girls in all 72 countries reporting greater levels of schoolwork-related anxiety than boys.

Increasing internet use

The report found students spent more than two hours online during a typical weekday after school and more than three hours online during a typical weekend day.

The majority said the internet was a great resource for obtaining information and more than half said they felt bad if no internet connection was available.

Students who spent more than six hours online on weekdays outside of school hours were more likely to report that they were not satisfied with their life or that they felt lonely at school.

They were also less proficient in science than students who spent fewer hours online.

The OECD research found that between 2012 and 2015, the time teenagers spent online outside of school hours increased by at least 40 minutes a day on both weekdays and weekends.

The study concluded that teenagers who felt part of a school community and had good relationships with their parents and teachers were more likely to perform better academically and be happier with their lives.

Students who felt their teacher was willing to provide help and was interested in their learning were about 1.3 times more likely to feel that they belonged at school, researchers found.

Those whose parents regularly talked to them were two-thirds of a school year ahead in science.

- Published19 April 2017