General election 2017: All or nothing for Labour on tuition fees

- Published

Labour is promising to scrap the system of university tuition fees

Scrapping tuition fees in England is the biggest and most expensive proposal in Labour's £25bn worth of pledges for education.

Instead of fees rising to £9,250 per year in the autumn, Jeremy Corbyn is proposing a complete handbrake turn in saying that university tuition should not cost students anything.

It's a bolder step than Labour's previous leader, who two years ago opted for a halfway house of cutting fees to £6,000 - and then was accused of pleasing no-one.

This is Labour going for an all-or-nothing approach - asserting free education as a fundamental principle - and creating the starkest choice in university policy for two decades.

It's a direct appeal to younger voters - with surveys suggesting that students are more likely to vote Labour.

It makes the pitch that no-one should be deterred from university because of the cost or fear of debt.

Will Labour's promise to scrap tuition fees appeal to younger voters?

Cost

Labour has costed the removal of fees - and the reintroduction of maintenance grants - as being worth £11.2bn per year.

And this is only England - because education funding is a devolved matter. There are no fees for Scottish students in Scotland and the Institute for Fiscal Studies says scrapping the lower fees charged in Northern Ireland and Wales would cost a further £500m per year.

This would be covered by the £48.6bn that Labour's manifesto says will be raised by tax changes - along with the party's other spending commitments.

But there are lower estimates.

Labour's figure is based on replacing the fees currently paid by students.

But the IFS and London Economics say the cost to the Treasury could be lower, when written off loans are taken into account, with forecasts around £7.5bn to £8bn.

Tuition fees have been abolished in German universities

Change of direction

Labour's big move on fees represents a complete of direction. Previously in government, Labour raised fees and in opposition proposed a modest reduction.

But they are now proposing to bulldoze the apparatus of fees, loans and repayments.

The most recent figures show £76bn is owed in student loans in England - with this level of student debt having almost doubled in four years.

From this autumn, fees will begin increasing every year with inflation and will soon glide past the £10,000 mark, with interest charges also rising to 6.1%.

And the Conservative government, before the election, had announced plans to sell off student debt to private investors.

Under Labour's plans, this whole push towards marketisation would be ditched - and universities would return to being directly funded by government.

Access

But is there any evidence that getting rid of fees would help more young people into university, including the disadvantaged?

Universities are worried that such a switch to direct funding, dependent on government finances, would put a limit on places and a brake on expansion.

The demand for university has risen among young people from all backgrounds

One of the quiet revolutions of recent years has been the complete removal of limits on student numbers - with universities able to recruit as many students as they can accommodate - and opening the door to rising numbers of graduates.

The argument for fees has always been that they provide the funding to allow more young people to go to university - and that a much smaller proportion went to university when there were no fees.

This year has seen a fall of 5% in university applications from UK students - and it follows a pattern of dips when fees are increased.

But the long-term trend has been relentlessly upwards, with a huge growth in demand for university places. It remains a powerful symbol of family aspiration.

Although wealthy families remain much more likely to send their children to university - entry rates have risen across all social classes, including the poorest.

Value for money

Do students get value for money from tuition fees? Is this an investment that is repaid in better job prospects?

Department for Education figures published last month showed that graduates remained more likely to be in a job than non-graduates and on average earned £10,000 per year more.

Among younger people, this graduate advantage is less, at £6,000 per year.

But the figures also showed that, despite rises in fees, graduate salaries have stagnated over the past decade.

Student vote

Labour's plan sends a strong political signal to young voters.

A survey from the Higher Education Policy Institute, taken before the manifesto publication, suggested that Labour is now more popular among students than it was in any of the three previous general elections.

The survey found Labour significantly ahead in the student vote.

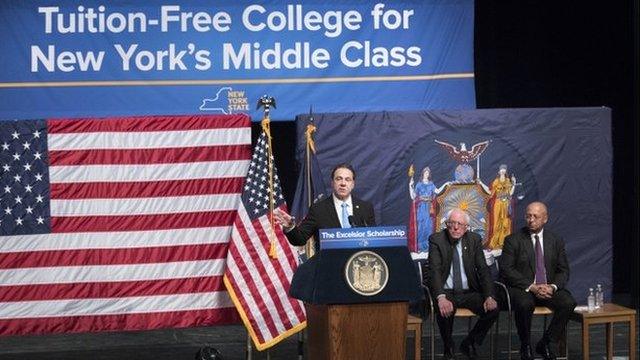

New York is removing tuition fees for families earning less than about £100,000

The Liberal Democrats, once the most popular party for students, are trailing in third behind the Conservatives.

Is this still the cloud of tuition fees hanging over the Lib Dems from their U-turn during the coalition government?

Could they really entirely scrap fees?

There will be plenty of scrutiny over funding Labour's plans. But there is nothing unprecedented or outlandish about getting rid of fees.

Germany has phased out tuition fees - and universities in the Netherlands and Scandinavia try to recruit students from England with the offer of low or no fees.

French undergraduates can study for low fees.

In the United States, New York state is introducing free fees for students from families earning up to about £100,000 per year, offering a handout to the squeezed middle classes.

There are now leading universities in the US which have lower tuition fees than in England. The University of Washington charges less than the University of Wolverhampton.

And the most immediate example of getting rid of fees has been in Scotland.

For England's voters, Labour's undiluted policy on tuition fees - proposing their complete abolition - offers the sharpest divide in the road for decades.