Have English universities been graded harshly?

- Published

LSE students at their graduation

Universities in England have learned this week about the results of a big new attempt to force them to care more about their undergraduates. The Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) has split them into groups depending on their teaching quality - gold, silver or bronze. And the results are a major source of controversy.

Universities must get silver or gold if they are to be allowed to raise fees in line with inflation in future. Southampton and the LSE have both received bronzes. York got a silver. There was local trouble, too. In Liverpool, the grand old Russell Group university got a bronze. But Liverpool Hope and Liverpool John Moores got gold and silver respectively.

Some of that shock, though, is by design. The British university system is built around research - not teaching. We already have a "Research Excellence Framework" used for distributing grants. The TEF is supposed to apply some pressure to redress that balance of interests - and a few bigger names were expected to struggle.

Oxford University, like Cambridge, got a "gold" rating

What do they say is being measured?

Half of the key measures that made up the TEF grades were drawn from surveys of students: their satisfaction with teaching, academic support and assessment. Others, though, were based on data on student retention and what the students went on to do. Universities got marks for their graduates' employability.

Crucially, they were not all compared crudely. These figures were all adjusted to account for the intake of the university, and the balance of courses on offer. So Southampton Solent and Southampton needed to achieve very different outcomes for their students, in the eyes of the judges. The idea was to identify universities doing well by their own students.

Universities could also make submissions to a judging panel, to explain why they believed the raw data might be misleading or unfair. But the blushes of some big names were not spared.

The LSE's measures, external, for example, show that it seriously underperformed, against the average hypothetical university with a similar subject and student mix, when it came to "the teaching on my course", "assessment and feedback" and "academic support". Gold-rated Northampton, external, meanwhile, is beating the spread on all those things.

There are edge cases: Southampton (bronze) and Bristol (silver) are very similar - but one fell short and one did not. (There are more cases here, external.) It is, though, hard to have too much sympathy for university leaders complaining about cliff-edges resulting from the use of a marking structure based around sorting people into a few big categories.

So what should you make of all this?

First, the reappointment after the election of Jo Johnson as universities minister means the TEF is here to stay - but what form it will take in the coming years is up for grabs. A major review of the TEF is already scheduled.

Second, this is a measure of teaching excellence, but does not involve any attempt to actually monitor teaching. That said, the idea of an Ofsted-style agency for higher education is something that academics are pretty unanimously against. So this sort of approach may be the only thing the sector will wear.

There is discussion of using earnings data - via a new database known as LEO, external - to supplement these measures. It would make employability a critical factor, which will trouble some academics.

The government is considering giving awards to individual courses: I am sceptical whether that sort of measure could be robust enough.

I am also a bit nervous about simply adding contact hours, or actual teaching time, into the scheme. It might end up - like Ofsted at its very worst - with the inspection process driving box-ticking behaviour and killing innovation.

There are questions, too, about the ability of universities to stand up to their students. Will using student surveys penalise universities where students are pushed harder? Will this power grade inflation?

There was, when this started, also an issue about undermining the idea of parity among universities. Historically, universities have opposed attempts by government to divide them into flocks. But that horse has bolted: differentiation is now becoming a fact of life for tuition fees. And it may become a more serious factor in, say, visa sponsor policy, too.

A graduate fashion show in 2014 from the University of Northampton, which won gold

But what is really being measured?

These are all bigger questions for another day - but, for now, I thought it was worth checking a few things.

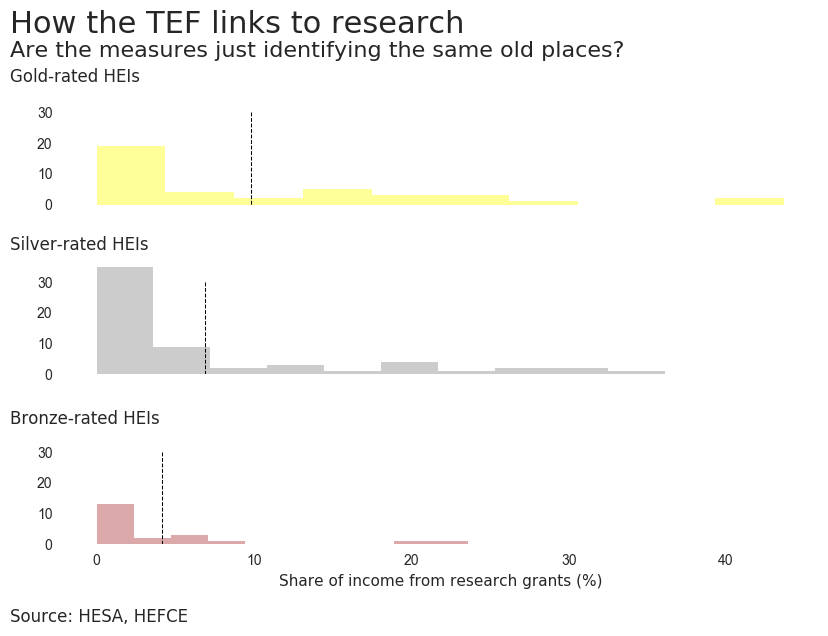

First, is the TEF actually mostly rewarding the usual suspects? We can look at the extent to which it is a simple measure of the traditional research hierarchy. Do universities who make higher shares of income from research do better on teaching? Here is a graph showing how the universities in each grade bracket fit together. The dotted line shows the mean for each category.

You can see the gold category universities are, on average, more research-intensive. The mean is higher (further to the right). You can also see the super-research-intensive universities are all in the gold bracket: the institutions whose research income is above 40% of total income. But also look at the distribution. The TEF is measuring is not a simple proxy for research-intensity. There is more variation within groups than between them on this measure.

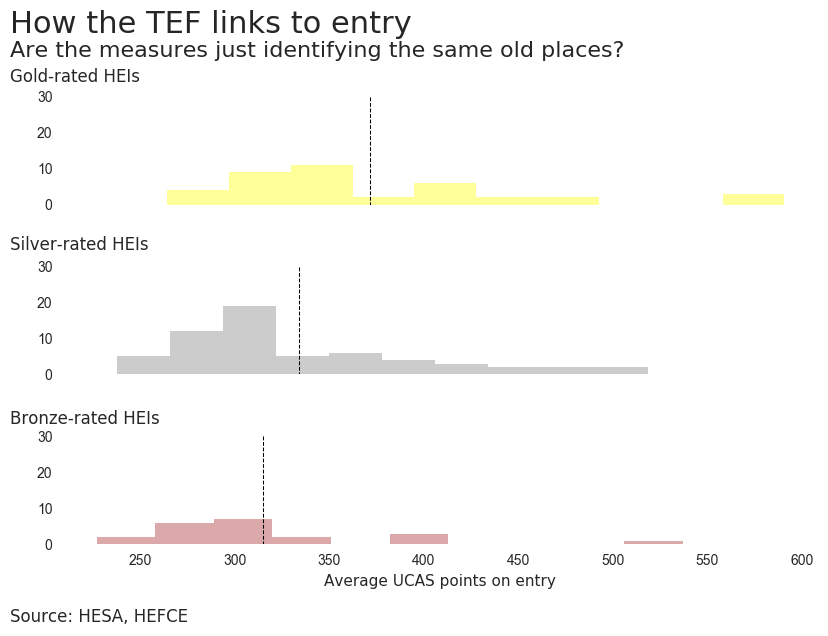

There is, though, a clearer link to average UCAS tariff points - a rough measure of the academic achievements of students before they enter the institutions. It does seem that, if you are recruiting higher-attainment students, it is easier to get a gold or silver.

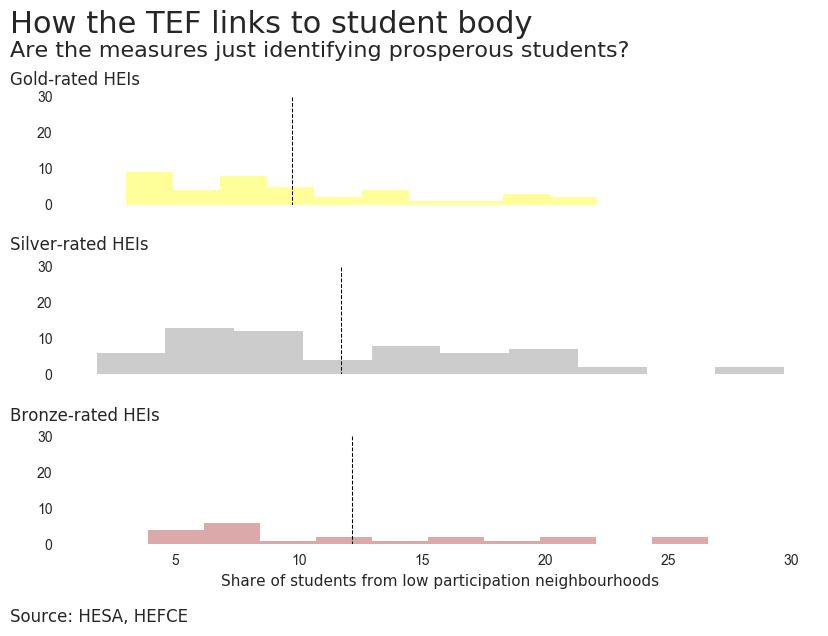

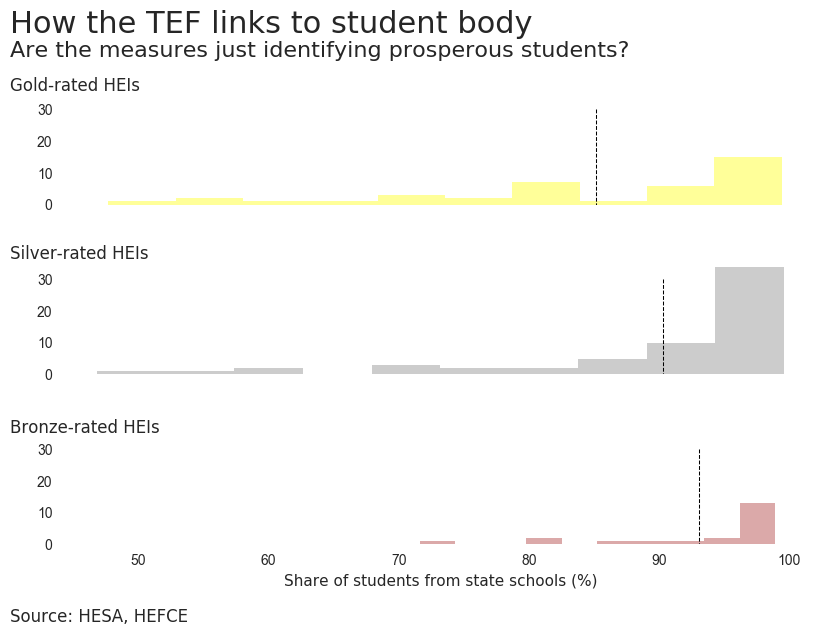

There was also a concern that the exercise would simply reward universities which took in more prosperous undergraduates - although the TEF was supposed to attempt to account for that through a "benchmarking" process. That is a bigger concern given that higher-prior-attainment institutions are doing better. So how have they done?

Here are similar frequency distributions on two widely used measures of the prosperity of university student populations. The first measure is the proportion of the student body from a "low-participation neighbourhood". That is to say: a poor area where fewer-than-average people go to higher education.

The gold universities, on average, have fewer poor students than the silver, which have fewer than the bronze. But the variation within TEF groups dwarfs the gaps between them. The TEF benchmarking has done a lot to avoid marking down universities that take poorer students.

But that choice of measure is very similar to the ones actually used in the TEF for benchmarking student populations. What, though, if you change your measure of poverty? All the universities where the share of state-educated students is under 70% are gold or silver institutions. None is bronze.

So what this means is that it appears to be easier to get a gold if you have more privately educated pupils. And so it is possible it is showing up that the benchmarking is not working. In effect, some gold universities' achievements may be inflated because we did not take sufficient account of their students' background.

If that is the case, it would mean some very grand universities have ratings that might need taking down a notch or two.