The social housing that never got built

- Published

"Claustrophobic" is how Llyle describes living in a studio flat with his girlfriend, Mehreen, and their toddler.

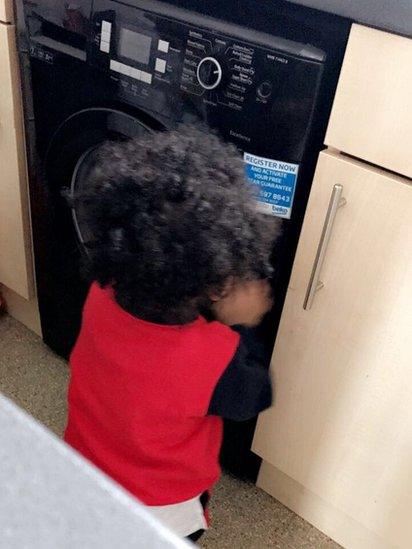

Isaac, one, has been walking since he was 10 months old, and his parents worry about him getting too close to the electrics in the tiny council flat in Ladbroke Grove, west London.

They've been on Kensington and Chelsea council's housing waiting list to upgrade to a two-bedroom flat since Isaac was born.

They made it to number eight on the list before Grenfell happened. Then, the housing list website went down "until further notice".

What they didn't know was that over the past seven years, developers in Kensington and Chelsea have been using legal loopholes to avoid building some 706 social homes in the borough, according to research by Shelter.

The housing charity found that developers have been winning building contracts from the council and promising to build a chunk of affordable homes in line with local planning policies.

But then the developers fail to deliver the homes, claiming that they would have made their property developments financially unviable.

'Double the rent'

Llyle, who has lived in the area all his life, said: "The thing is, if we move out of this flat I lose my right to a council tenancy, and that would be to go against everything I've done in my life.

"To rent a studio flat privately would cost more than double our rent now.

"To rent a two-bedroom flat privately would cost four or five times as much. We couldn't afford to live in Ladbroke Grove.

"I am not going to go down the town hall and make a big thing about, but it would be good to know where we stand.

"It gets unbearably hot in the flat and we are worried about Isaac's safety."

One of the 700 or so properties developers were supposed to have earmarked for social housing as they built and sold new homes in the borough would have done very nicely.

'Aspirational targets'

Unfortunately for Llyle and his family, developers in Kensington and Chelsea have been using what are known as "viability assessments" to reduce the amount of social or affordable housing they were required to build in the borough.

Kensington and Chelsea originally required 50% of new builds, across 96 schemes built since 2010, to be social rented homes or affordable homes for sale.

Lyle and Mehreen would like more space for their toddler

But as a result of the use of viability assessments, the rate of social housing in new builds reduced to 15% in the borough, according to Freedom of Information requests made by the charity.

Planning director at the Home Builders Federation, Andrew Whitaker, said all affordable housing requirements were "aspirational targets" and were based on an individual site's viability.

"Without a willing landowner and developer you get no development and thus no affordable housing," he said.

Once viability assessments are completed, and if they are agreed independently, the developers are excused from having to deliver the affordable housing they promised.

Sometimes - but not always - the developer has to pay the local council a contribution towards building social housing elsewhere instead.

The building of social homes for rent is at a 24-year-low in England

In 2011, central government stopped funding social homes to rent

It focused instead on affordable homes to buy and to rent at 80% of market rates

The building of social homes fell from 36,000 to 3,000 by the next year

Instead social rents are cross subsidised by the sale of private homes for sale

There are one million people on waiting lists for a council/housing association property

Shelter's chief executive Polly Neate says she fears this may be happening in many places across the country at a time when there is a desperate need for more affordable homes.

Calling for the government to close the loophole, she said it was wrong that big developers were allowed to "prioritise their profits by building luxury housing while backtracking on their promises".

The leader of Kensington and Chelsea Council, Elizabeth Campbell, said: "Grenfell has focused everybody's minds on the issue of housing and we want to find solutions."

She said the borough was "getting tougher" with developers and argued that viability reports can still result in the ability to build more homes, as developers could be asked to pay for the opt-out.

But that doesn't change things for Llyle, Mehreen and Isaac.

"If we had a timeframe then at least we could plan properly and decide what we need to do," said Llyle.

"It's very frustrating because we can see what's going on - they're pushing people out."

- Published18 July 2017

- Published7 February 2017

- Published19 September 2017