Learning to speak Shakespeare like the actors do

- Published

Between them Stacey, 14, and Maleeha, 13, speak six languages - now they both speak Shakespeare as well.

That's just as well, as the work of the 16th Century dramatist and poet forms as much as a quarter of the marks for some English GCSEs.

To do well in this key exam, in which the results are crucial to schools, pupils need to become comfortable with the complex poetry of Elizabethan England.

Beautiful though it may be, the language does not sit easily with the staccato, text-speak and Instagram posts of today's modern teenager.

And one might assume it would be harder for pupils who speak languages other than English at home.

These pupils from Barking - a culturally diverse part of east London - were not always so fluent with the Bard.

"When I first saw it.. Shakespeare I mean... I didn't really want to read it," says Stacey.

But the Year 9 pupil describes how she was given a kind of "code" to the language, along with her classmates at Eastbury Community School, external.

As one of the Royal Shakespeare Company's associate schools,, external pupils were helped by a specialist from the theatre company's education programme.

She worked with the class, helping pupils to unlock the language using tried and tested techniques.

'Now willing'

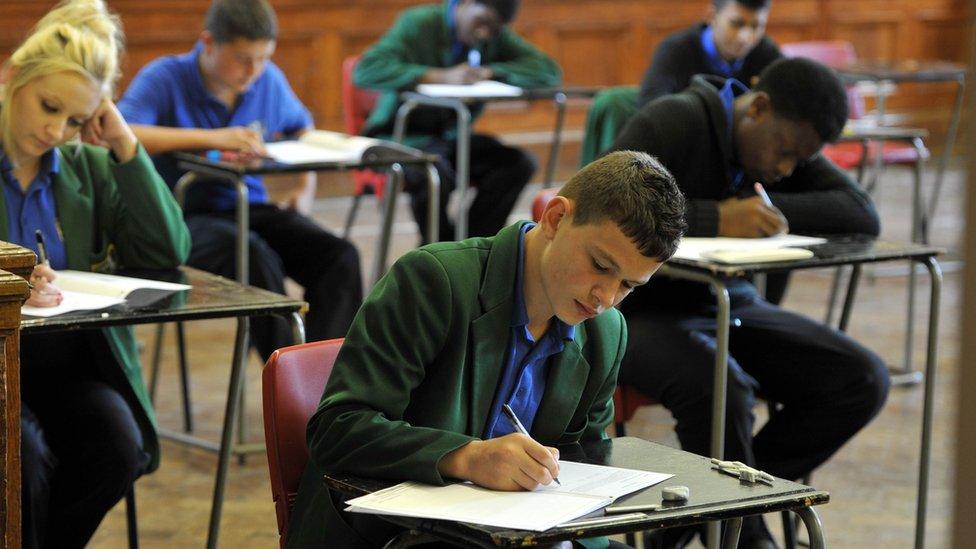

Rather than sitting at desks, books open, pupils are taught to read the texts in the same way as actors do in rehearsals; on their feet, and from punctuation mark to punctuation mark.

Pupils are encouraged to get inside the minds of the characters, to see how they fit together with others in the jigsaw of the play.

They also get to see an RSC performance.

"I began to understand. It was like I had the code," Stacey said. "So when I went on to another play, I felt quite well informed because it was the same. I could break it down, see how it fits together and try to make sense of it.

"Now I understand it, well most bits," she says, "and I am willing to pick it up and read it."

Her classmate, Maleeha, recalls being given scenes to digest and work on with a partner.

Once they had got the basic understanding of the scene, the class would be "like some sort of forum", she said.

'"We would debate extensively about what a single word on a line meant."

David Dickson says his pupils are now enthusiastic about Shakespeare

Eastbury's executive head teacher David Dickson says, with a twinkle in his eye, his pupils have become so enthusiastic, that he has, on occasion, had to break up disputes about interpretation of the text.

"I can remember what it was like teaching Shakespeare before we worked with the RSC," he says.

Last year, the school's GCSE pupils achieved the highest marks in England in the Shakespeare part of the exam.

And yet nearly two-thirds of Eastbury's pupils have English as an additional language.

However, the school rightly makes a virtue of the many different languages its pupils speak.

One might assume that juggling more than one language might hold back pupils' understanding of Shakespeare.

Not so, according to the RSC, as children with English as a second or additional language tend to do very well when Shakespeare is taught in this active way.

Its director of education, Jacqui O'Hanlon, says: "We find that Shakespeare levels the playing field - the language is new to everyone - and learning happens on your feet."

'On our feet'

Paul Clayton, head of the National Association for the Teaching of English, says the teaching of Shakespeare has become "dry and formulaic" in some schools, as teachers deal with the pressure of having to produce good results.

And, with the combined English GCSE contributing 30% to the progress scores with which schools are held to account, those pressures are very real.

"Sometimes there is a lot of mention of assessment objectives produced by the exam boards that they're following," he says.

"And we see lessons can be organised around the kind of questions that pupils are going to see in the exam. That does narrow the children's experiences of these plays," he adds.

"What the RSC approach does is it proves that you can teach in creative ways that engage pupils and still get good results."

Mr Dickson adds: "One of the differences I see, which we all seem to enjoy, is that we are doing Shakespeare more on our feet.

"And that pupils are having fun and they're working and I don't think that they realise they're working and learning."

Mrs O'Hanlon says: "Our key message at the RSC is that Shakespeare is for everyone. It's not for a particular section of society.

"The work that we do in the education department is to equip young people to really take the work on, and get their hands on it."

- Published23 April 2018

- Published19 October 2017

- Published26 May 2017

- Published19 May 2017