League tables changes ‘toxic’ for poor white schools

- Published

The way secondary school league tables in England are now devised is unfairly stigmatising schools in white working-class areas, head teachers say.

They say the format is "toxic" for schools with a combination of high levels of deprivation and few pupils speaking English as a second language.

"Disenfranchised" communities will be even more disillusioned if their schools are unfairly blamed, say heads.

The Department for Education says the revised rankings have become "fairer".

Geoff Barton, leader of the ASCL head teachers' union, said the league-table changes had been welcomed as an improvement but the patterns emerging meant it was "definitely time to look at it again" and talks with the Department for Education were expected.

'Isolated and disenfranchised'

Hundreds of thousands of teenagers are currently taking their GCSEs - and the results will be used in the next round of school league tables.

But there are complaints from heads in the North West that the measure for comparing schools, known as Progress 8, is skewed against schools serving deprived white communities.

"If this was any other ethnic group at the bottom, people would be unsettled," says James Eldon, principal of the Manchester Enterprise Academy, where 90% of the GCSE year are eligible for free school meals.

"But because it's the white working-class, it's somehow less controversial," says Mr Eldon, who chairs the secondary head teachers group in Manchester and is chief executive of an academy trust.

He warns of the "disillusionment" for communities already feeling "socially isolated and disenfranchised".

White working-class boys have one of the lowest rates of entry to university of any group.

Winners and losers

Mr Eldon says the new league table measurements were brought in with good intentions, but are having unintended consequences.

Progress 8 was meant to move beyond comparing only final results - and instead measures the progress that pupils make between primary school and GCSEs.

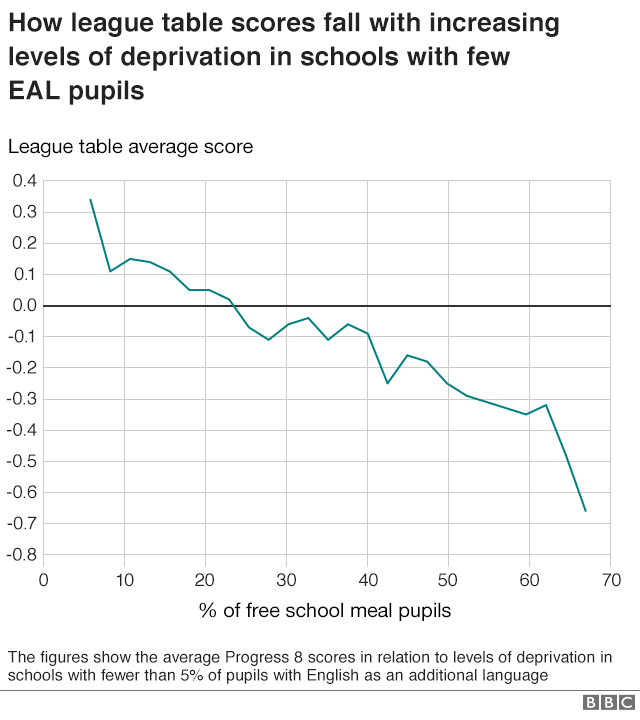

Heads have analysed the link between deprivation and scores in schools with few EAL pupils

It was introduced to be fairer, so that pupils who began secondary school from a low base would be measured on how much progress they had made.

Ian Butterfield, head of Hindley High School, in Wigan, says the flaw in the system is not taking deprivation into account.

Pupils in schools with a more deprived intake make less progress through secondary school - and will therefore be given a negative score in the league tables, he says.

Another factor is that "English as an additional language" (EAL) pupils, sometimes starting from a lower base, are likely to score higher on the measure of progress.

There are also cultural factors - with EAL pupils often migrants from families with strong support for their children's education.

The "winners" in this system are more affluent schools, where pupils on average make better progress, and those with more EAL pupils, Mr Butterfield says, with London the most successful example.

League tables are based on progress rather than final results

But for white working-class schools, such as in parts of the North West and North East of England, with a very poor intake and few EAL pupils, Mr Butterfield says, it is "almost impossible" for them not to have a negative score.

He says the league tables are not measuring the achievements of schools in adversity but describing the demographics of their intake.

Professor Becky Allen, Director of the Centre for Education Improvement Science at UCL, said: "The problem with school performance tables is that they assume that the schooling system is solely responsible for everything that children learn during their childhood.

"So, if white working-class students learn less than other students, the blame for this lesser progress is entirely placed on the schools. Of course, this notion is nonsense - learning is co-produced by the actions of schools, parents, communities and the students themselves.

"The dilemma for government is what we do about this. Should we just accept that schools serving white working-class communities will have less good exam results? And how can we be sure that these schools are working as hard as they can to provide a high-quality education?"

But the head teachers' concerns have been backed by Dr Terry Wrigley, of the University of Northumbria, who has written a report for the National Education Union about why so many schools in north-east England are appearing to do so badly.

Almost twice as many are below the minimum "floor" standard, compared with the national average.

"This is not special pleading or complacency," says Dr Wrigley. "Poorer areas are being unfairly penalised."

As pupils go through secondary school the impact of deprivation grows, with less well-educated parents not able to help as much with homework and higher risks of disaffection. The gap in vocabulary can also widen and poorer youngsters are less likely to have families making sure they are on course for university.

Dr Wrigley says that Progress 8 seems to mirror levels of affluence and poverty and is "an unreliable identifier of school ineffectiveness".

Recruiting staff

Head teacher Mr Butterfield says there are serious consequences for schools - with Ofsted likely to intervene and schools' leaders at risk of losing their jobs.

He warns it is becoming a serious disincentive when trying to recruit staff.

"Start labelling all these schools as failing and you begin to destroy local communities and the confidence of those dedicated to improving the lives of these youngsters," says Mr Butterfield.

Mike Kane, shadow schools minister, has asked whether the rankings will be amended

Mr Eldon says teachers in such areas have worked hard to turn around attitudes where it was "soaked into the bones" that local schools were bad.

Labour's shadow schools minister and MP for Wythenshawe, Mike Kane, has asked the government whether it will amend the league tables in the light of the impact on schools serving white working-class pupils.

A Department for Education spokesman defended the league tables as making sure that schools focused on the results of all pupils, including low performers.

"Far from being unfair, our Progress 8 measure means that schools are now recognised for the progress made by all pupils, as every grade from every pupil contributes to the school's performance - taking into account their ability when they started school," said the spokesman.

"The measure has been broadly welcomed by the sector, as it is a fairer way to assess overall school effectiveness as it doesn't focus on the attainment at a particular grade threshold."