Ofsted admits some 'outstanding schools aren't that good'

- Published

- comments

Some schools rated outstanding may no longer be as good as their rating suggests, Ofsted has said amid official criticism of its work in England.

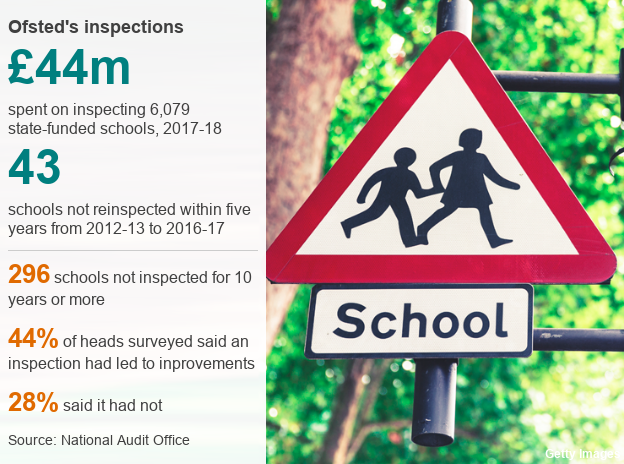

A National Audit Office report found 1,620 schools, mostly outstanding, had not been inspected for six years or more, and 290 for a decade or more.

Outstanding schools were decreed exempt from routine inspections in 2011.

Ofsted bosses said there was no way of telling if these schools had since fallen into a "mediocre" category.

Although, inspections can be triggered at any school if a safeguarding concern is raised, or if there is a significant drop in results.

It no longer goes into these top-rated schools on a regular basis.

'Effectiveness reduced'

Ofsted's director of corporate strategy, Luke Tryl, said: "What we can't tell is if the levels of education in those schools judged outstanding 10 years ago are the same or whether it has changed to become middling, or mediocre or coasting."

When asked by reporters if he was saying that some "outstanding schools aren't really outstanding", he replied: "Yes."

However, many schools will have their "outstanding" label highlighted on their websites and on banners outside their premises.

And many parents base at least their initial views of such schools on these Ofsted rankings.

The NAO found the inspectorate's "effectiveness has reduced" as a result of the decision by the Department for Education and Ofsted to end routine inspections for outstanding and good schools.

Ofsted said it had since been lobbying the DfE to reinstate routine inspections every six years for a primary schools and every five or seven years for a secondary.

Schools minister Nick Gibb said: "If Ofsted has reason to believe a school is no longer meeting its previous high standards, we would expect it to use its powers to carry out a full inspection - this has always been the case - and remains so."

He added that the inspectorate was given £40m a year to provide a school inspection regime that is focused on the schools that need the most improvement.

Lack of inspectors

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said most parents were "savvy enough" to look at a range of evidence on school effectiveness and did not just rely on Ofsted rankings.

His organisation has also been arguing for inspections of outstanding schools to be reinstated, calling for one every five years or so.

The schools inspectorate was also found to have missed its own targets on the re-inspection of the weakest schools - those rated inadequate.

The target of 24 months for such a re-inspection had been missed in 6% of cases, 78 schools, between 2012 and 2016, the NAO said.

These schools would have weak teaching, weak leadership and possibly some behaviour issues, Ofsted said.

The NAO report said: "Ofsted has extended some of the targets to allow schools more time to improve.

"This has also allowed Ofsted to spread re-inspections over a longer period."

But Ofsted told the NAO it had found it difficult to meet its inspection targets because of cuts to its budget and because it did not have enough inspectors.

In 2015, it took a decision to bring all its inspectors in house after a string of complaints about inspections that had been contracted out to private companies.

This had left it with a shortfall of inspectors, although this had improved in 2016-17, the NAO said.

'Cuts and shifts'

Matthew Coffey, Ofsted's chief operations officer, defended the decision to effectively reduce the number of inspectors, saying it was taken on quality grounds.

But he added that some of its most senior inspectors, HMIs (her majesty's inspectors), had left to run some of the numerous multi-academy trust chains being formed at the time.

He said: "Becoming an HMI used to be a traditional end of career role, and it's not like that any more."

"It was a challenge", he said, to compete with academy trusts able to pay salaries of £100,000 or more.

HMIs were paid about £70,000, he said.

Amyas Morse, the head of the NAO, said: "The fact that Ofsted has been subject to constant cuts over more than a decade, and regular shifts in focus, speaks volumes.

"It indicates a lack of clarity about how best to obtain assurance about the quality of schools.

"The department needs to be mindful that cheaper inspection is not necessarily better inspection.

"To demonstrate its commitment, the department needs a clear vision for school inspection and to resource it accordingly."

Nick Brook, NAHT deputy general secretary, said it was essential to hold schools to account, but the current system was muddled.

"Schools and parents alike will be concerned to read that the NAO has concluded that the level of independent assurance about schools' effectiveness has reduced. Confidence in the quality and reliability of inspection is of paramount importance to all."

- Published11 October 2017

- Published19 November 2017

- Published21 March 2014