Adverts bid to end paramilitary-style attacks in NI

- Published

A picture from the Ending the Harm campaign after a young boy is driven to an "appointment"

In a packed Belfast hall, there is a silence as a set of new TV and radio adverts are given their first public airing.

They are chilling. The screams of a young lad, lying on the floor, calling for his mother after being shot in the knees, are difficult to listen to.

This is a radical step by authorities. The adverts have been commissioned by the Department of Justice in Northern Ireland.

The decision to run this type of hard-hitting campaign - which is bidding to end so-called paramilitary-style attacks - was not taken lightly.

"Paramilitary-style attacks are what we, in Northern Ireland, call vicious shootings and beatings given out to individuals by so-called paramilitaries," said Anthony Harbinson, chairman of the Tackling Paramilitarism Board.

There have been 87 such attacks over the past year, he said, often on young people.

"These paramilitaries style themselves as protectors of communities. They would like to see themselves as a second police force, dealing with individuals within their communities, who have stepped outside the law," he added.

The adverts show a reconstruction. A tearful mother drives her son to an appointment, in which he is to be shot in both legs by masked men.

"Again!" comes the order, as you hear the second shot fired into the back of the crying man's knee.

"Paramilitaries don't protect you. They control you" is the accompanying slogan.

The ad tells the story from the points of view of those involved - the victim, his mother, the gunmen and a witness.

The adverts will be given significant exposure, running on TV and radio across Northern Ireland and in cinemas - it is an unprecedented step.

They will be deliberately aired straight after widely-watched programmes such as The Great British Bake Off on Channel 4.

The scenes are played by actors, but for some in Northern Ireland living in fear of violence is a reality.

One young man, who says he is under threat from paramilitaries, described his situation through youth workers who are supporting him. His identity has been protected.

"The paramilitaries put the word out that I needed sorted. I got kicked out of school because they said I was a risk to the other kids," he said.

"They said they were 'protecting the estate' from me. My family tried to speak to them but they didn't want to know.

"I'm trying to change and do better but I'm always on edge, always looking over my shoulder, waiting for it to happen.

A survey found that 35% of people believe these attacks are justified.

"I want to live back at home with my ma, but I can't. I can't let her see me get beaten by hammers or shot."

'Tacit endorsement'

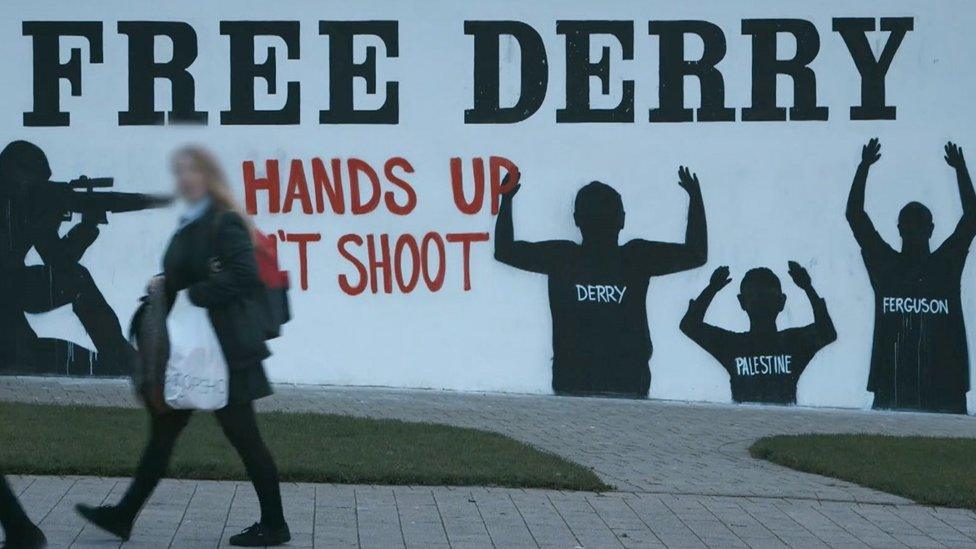

In Northern Ireland this is not only a criminal justice issue, but a battle for hearts and minds.

A survey carried out by the Tackling Paramilitarism Board found that 35% of people believe these attacks are justified.

"The 35% isn't who you might think it is," said community worker Paul Smyth.

"I've had youth workers, teachers, civil servants, tell me privately that actually they're OK with these attacks, that they sort out local problems. I also think our politicians have been pretty woeful at speaking out about this."

Authorities hope the campaign will help end "tacit endorsement" of these crimes.

But in Northern Ireland, some attitudes are deeply ingrained.

'Revenge or vengeance'

"People don't care if these attacks work," explained Debbie Watters, who works with Alternatives, an organisation that helps those under threat.

"All people care about is that they've got revenge or vengeance. They don't care if it changes the person's behaviour."

"The sole aim is instant, visible, vengeance and justice. Then they feel this has worked for them."

She wants to see criminal justice measures made more effective and visible.

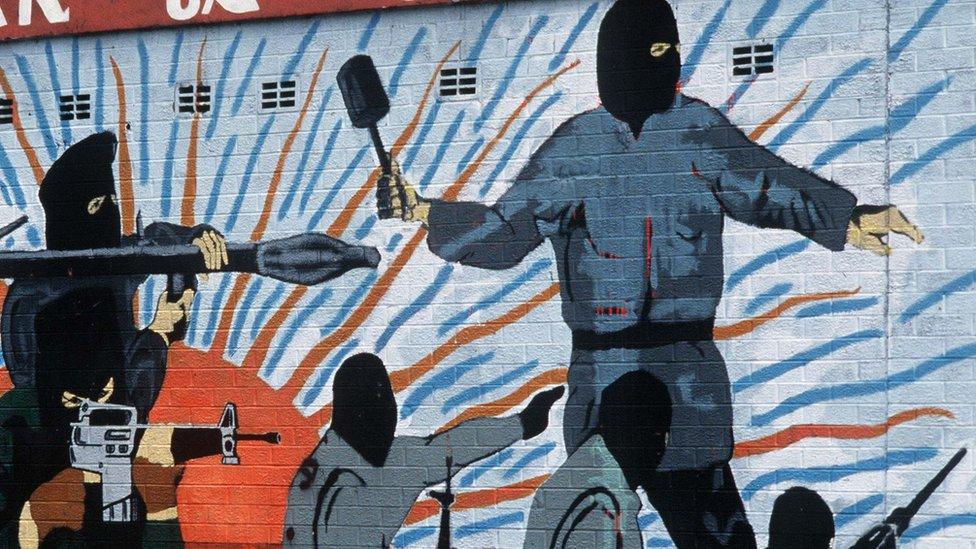

Paramilitaries were once involved in armed campaigns, but now say authorities, they are simply criminal gangs.

Communities are still rebuilding following the 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

"What are authorities doing to help the young people who become the victims of these attacks?" asks Stephen Hughes, a youth worker who has himself been subject to threats for speaking out.

"There is not enough support for these young people when it is needed."

He and some others are sceptical of the authorities' current approach.

The police said the attacks were a "throwback to another time"

Intimidation and threats mean victims and witnesses are unlikely to give evidence, so convictions for these so-called punishment attacks are rare.

It is hoped that the campaign will help to change that.

"This is un-normal, and unnecessary in 2018," said Det Ch Supt Raymond Murray from the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

He added: "It is throwback to another time. We can't have people shooting and beating people in houses and streets, as some sort of pseudo police force."

"We should not attach justice to this sort of activity. It is gratification."

Police have said they are clamping down on the gangs in other ways.

'Done in my name?'

Recently, explained Det Ch Supt Murray, there have been large drug seizures, and confiscation orders for cars, houses and cash - luxury items that the bosses of these organisations enjoy.

But authorities believe the solution to this does not only rest with policing.

"Why do some people go to these gangsters and ask them to mete out justice?" asked Mr Harbinson.

Communities are still rebuilding following the 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland known as 'the Troubles'

"We have to get it through to the community that police will not solve this alone. We have to take a societal approach in changing what people perceive is right and wrong."

No-one is quite sure what the response to the emotive advert campaign will be.

It may be a risky approach, but those behind the campaign believe it is justified.

"We want to ask people to ask themselves, why is this happening in my community? And is this being done in my name?" said Mr Harbinson.

If community support for paramilitaries ends, the theory is, so will the attacks.

- Published28 September 2018

- Published2 October 2018

- Published23 September 2018