Budget 2018: Why schools need more than 'little extras'

- Published

Philip Hammond, the chancellor, holds his red box

Philip Hammond managed something pretty impressive this week; he gave schools an extra £400m while irritating them deeply.

This remarkable achievement came about because he said the money was for "little extras" that schools might need. He appears to have misread the mood in staffrooms.

To understand why that dismissive comment is so annoying to teachers, there are a few things worth considering about where we are with English schools.

The most important fact is that the school system is using even more red ink than usual; the school system's financial position is deteriorating across the board.

This ought not be too surprising; schools' spending per capita has fallen by 8% since 2010.

In 2016-7, 61% of primary schools and 68% of secondary schools ran deficits. School reserves in 2016-17 were £1.7bn, a single-year decrease of £384m.

There are also policy decisions on schools that have been made more financially vulnerable in recent years; a fundamental purpose of the old local authority system of schools, prior to the coalition's school reforms, was risk-pooling.

Schools were shielded from small unforeseeable financial shocks by sharing costs with neighbouring schools.

Today, about one in three primaries and two in three secondaries are academies. These are schools outside that pooling system.

They get a fixed sum from the DfE for the year. They can be parts of multi-academy trusts that can do some sharing, but only about half of academies are in a chain of more than 5 schools. One in five is a standalone school.

That is a pretty shallow pool.

Taken together, this means that a lot of schools are hitting the edges of their balance sheets and have had no choice but to cut costs. That is awkward in schools, whose main cost is teachers.

But there is more; we have not been preparing our heads for this mission.

Raising standards?

Since the early 1990s, governors and heads have had a lot of financial and curriculum autonomy. Accountability has, however, changed dramatically in that time.

The introduction of Ofsted and league tables followed by hardening performance incentives for schools has successfully focussed attention on raising attainment. We have applied increasing pressure on the classroom for decades.

This performance focus has made school leaders focus on it to the exclusion of all else. Value for money has not been a major concern.

In fact, heads have previously been discouraged from, for example, running large surpluses that would enable them to improve their facilities or build a rainy day reserve.

Schools that have become academies in recent years have not been schooled in how to run these little businesses. Instead, they have been swaddled in rules and form-filling from the centre.

And the management challenge of running a school is not easy; they are little institutions, but delicate ones. And, in large part, a bit of a logic puzzle.

There are iron laws that schools must obey: you need a teacher in each class. There are limits to what you can do to cut back the number of teachers in a department without having to abandon the subject.

If you abandon subjects, that is awkward, too.

But there's another effect. Trying to screw higher performance out of teachers through accountability has reached the limits of what it can do. We are beating the horse as hard as we can and it won't run any faster.

What it is doing, however, is making teaching a less enjoyable job - and a minority of teachers are deciding to jack it all in.

A new NFER report, external highlights the damage.

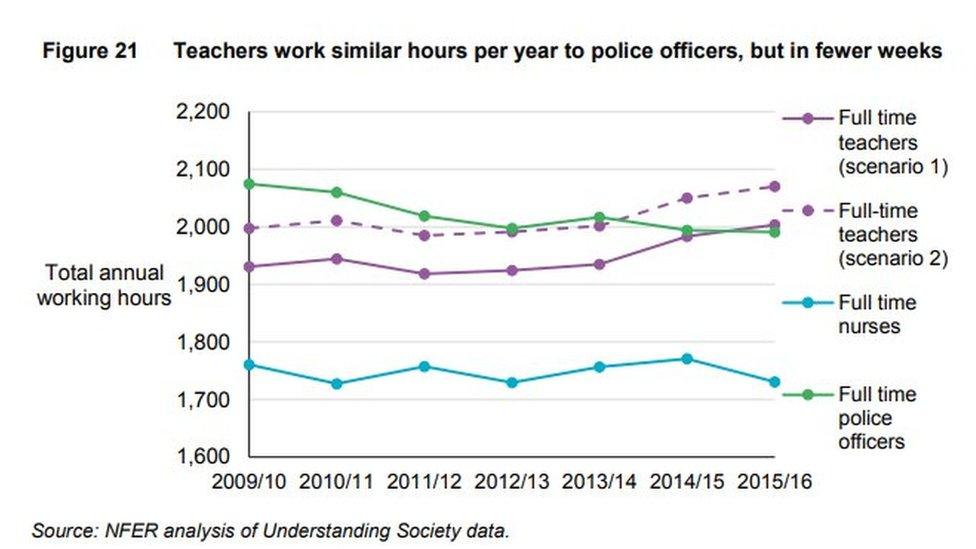

Teachers now work as many hours as police officers and many more than nurses, even when you include their holidays. But the work is squeezed into a relatively small number of weeks a year.

(If you take one thing away from this article, it is that you should stop making jokes to teachers about their easy lives and long breaks.)

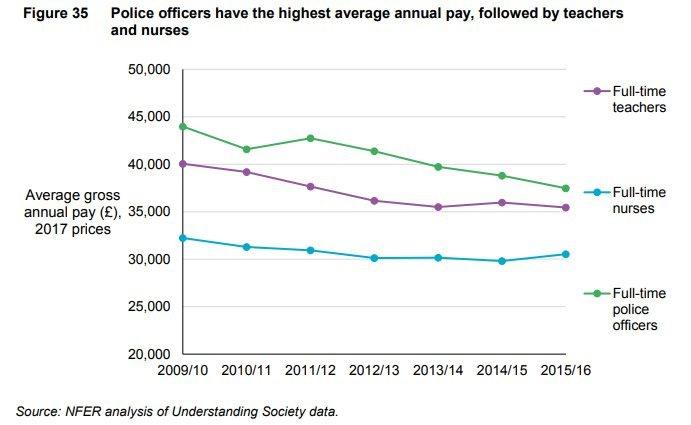

This is surely the key to why teacher retention is deteriorating. Part of this must be because teachers' pay has been squeezed harder and harder.

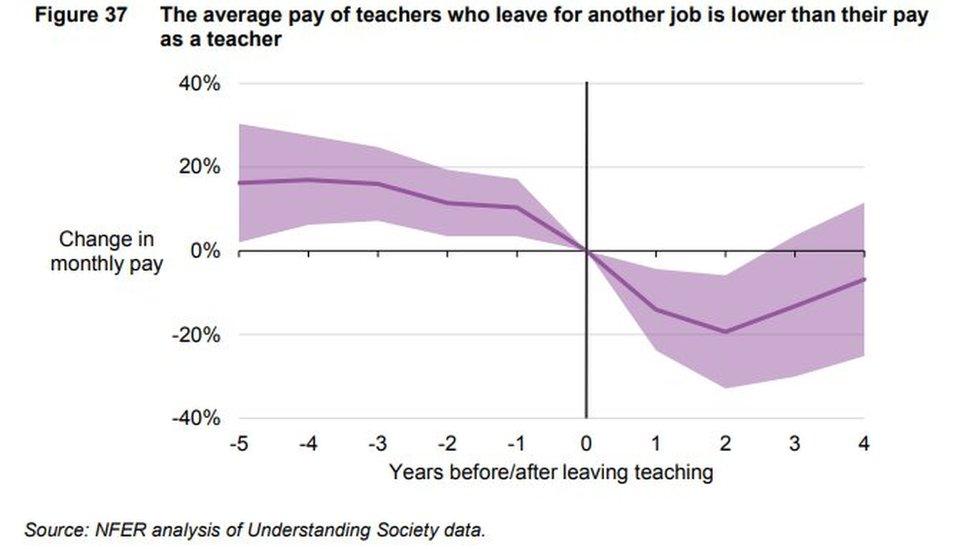

But it is striking that the NfER has found people are leaving teaching for less money. They just want less stress and fewer hours.

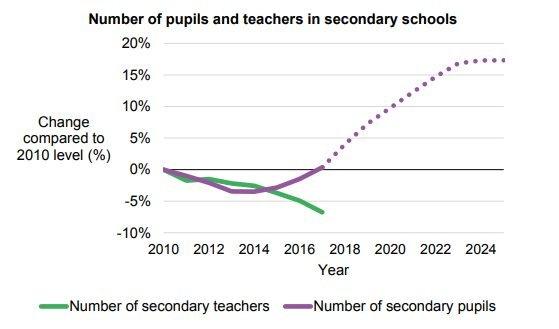

The problem is that this is coming just as the need for teachers is rising.

This retention problem is soluble. Ofsted is trying to stop pointless makework.

And the good news is that there is a stock of teachers who show willing to return, perhaps part-time.

The National Foundation for Education Research says the data implies there may be "unmet demand for part-time work for secondary school teachers that drives some to leave [full-time teaching]".

But managing a workforce with a larger number of part-time teachers is likely to be mean more management strain. And there is no good answer to these problems that won't mean more money.

Schools are not in the state that adult social care or prisons now are. We should probably reserve words like "crisis" for what is happening there. But things are certainly quite bleak.

This is about more than "little extras".

You can watch Newsnight on BBC 2 weekdays 22:30 or on iPlayer. Subscribe to the programme on YouTube, external or follow them on Twitter, external.