Child protection services near crisis as demand rises

- Published

Social workers on the hardest part of their job

A steep rise in vulnerable children needing protection over the past 10 years is pushing council children's services in England into crisis, suggests research.

There has been a substantial increase in calls from the public and professionals worried about a child, according to a study for the Association of Directors of Children's Services.

The number of investigations where a child is believed to be at risk of significant harm has also more than doubled.

Over the past year, almost 2.4 million people contacted children's services because they were worried about a child - a 78% increase on 10 years ago, while serious investigations over concerns of significant harm are up from just under 77,000 in 2008 to almost 200,000 last year - a rise of 159%.

Council leaders have warned they will have to overspend their budgets to meet demand, though the government says extra money was announced for children's services in the Budget and it is working with councils to ease the pressures and improve children's lives.

So why are services designed to protect the most vulnerable children in society facing such a squeeze?

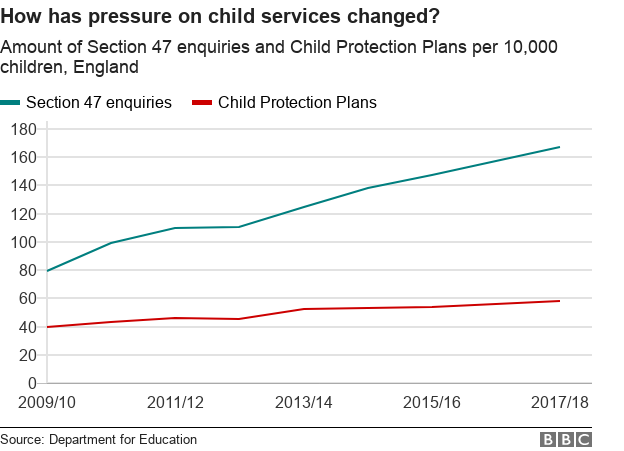

1. A considerable increase in demand

The past decade has seen pressure increase across the board in the child protection system - the number of calls from people concerned about a child has nearly doubled.

Some of that rise may be down to better awareness but there has also been a substantial increase in children placed on child protection plans, where social workers monitor the way a child is being looked after to keep them safe.

The steepest rise has been in the most serious Section 47 investigations. These are carried out when there are fears that a child is at risk of significant harm.

In such cases, the stakes couldn't be higher.

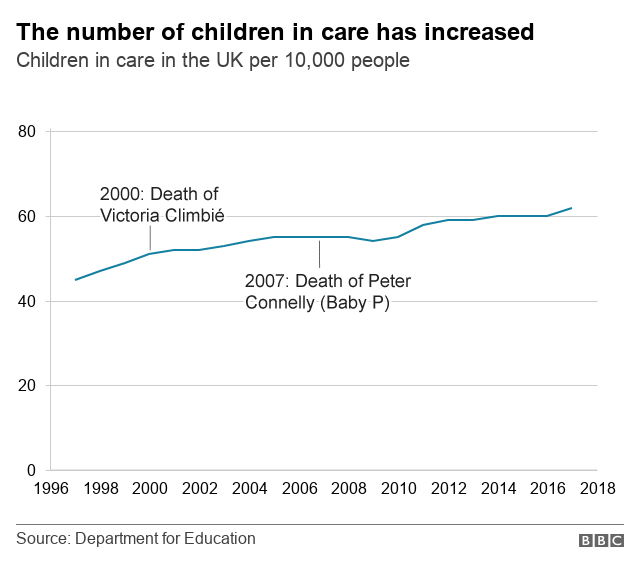

Social workers, police and other agencies, involved in these investigations, will all remember the deaths of children such as Victoria Climbié in 2000, external and Baby Peter Connelly in 2007.

Both were known by the authorities to be at risk but still died at the hands of people close to them.

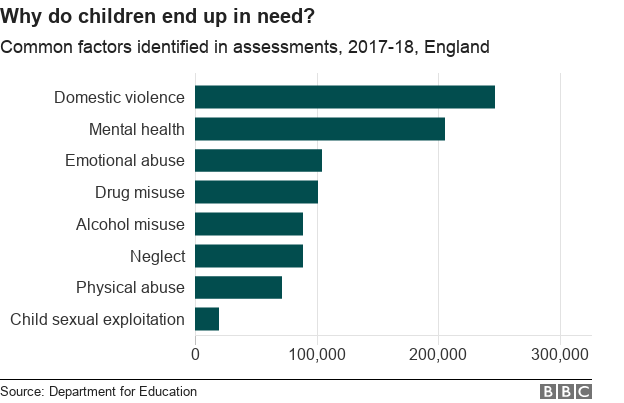

2. Domestic violence is behind nearly half the cases

In nearly half of the cases, where social workers carry out an assessment, domestic violence is a factor. The next most common issue is mental health problems.

Of the children then placed on child protection plans, the concern in most cases is that the child is being neglected.

That is a failure to meet their basic needs, which could, for instance, mean they don't have enough food, the home is cold and they have nowhere to sleep.

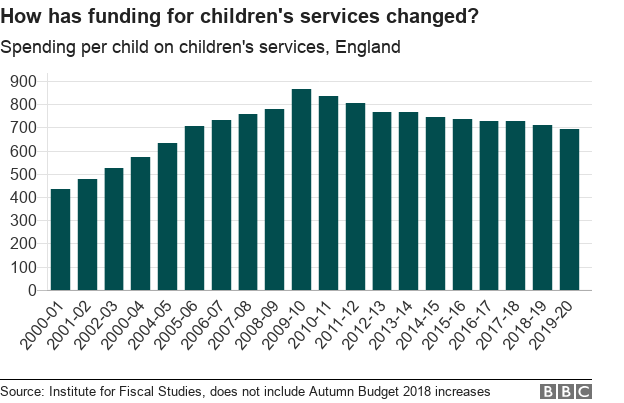

3. Funding has dropped since 2010...

Throughout the era of austerity, while councils have made cuts elsewhere, they maintain they have tried to protect spending on children's services.

But once inflation is taken into account, the money available to protect children has still fallen significantly. That combined with increasing demand and more complex cases has led to councils overspending their budget for children's services.

With finances so tight, money has often been concentrated on statutory services, which protect children at risk of neglect or abuse.

This has meant cuts to the early intervention teams, who might have been able to ease future pressures.

In the last month's Budget, the government announced an extra £84m for children's services over five years.

4. ...but the number of social workers has increased

Finding and keeping front-line staff in this high-pressure world is a constant issue for local authorities.

The most up-to-date figures show a slight increase in the number of social workers but a third will have been with their current local authority for less that two years and 15% will change jobs during the year.

There are a high number of vacancies, with an average of 17% of posts empty. Many of these roles are taken on by the more than 5,300 agency social workers in the system but that comes at a cost.

Agency staff are paid more than council staff and figures collected by the BBC show between 2012-13 and 2016-17 local authority spending on these temporary staff nearly doubled, reaching £356m.

It is money cash-strapped councils can ill afford. Even more importantly, frequent changes in social worker are damaging for a child. It is much harder to learn to trust the person there to help you, if they keep changing.

5. Children in care have increased by a quarter

Most children that social workers are involved with will remain with their families but the numbers removed from their home and taken into local authority care have risen by 24% in a decade.

Of the more than 75,000 children looked after by the state, most will have faced abuse or neglect.

Other reasons for a child being in care include family dysfunction or because their family is in acute distress. A small number of children will be there because of their disabilities.

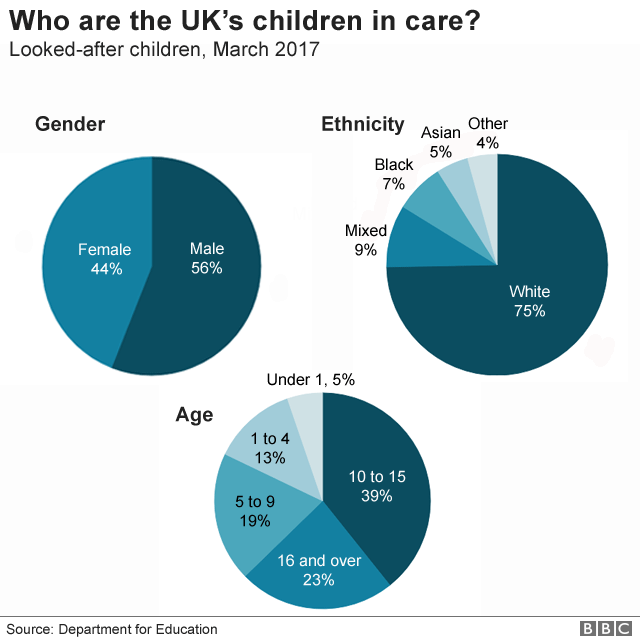

6. Most children in care are older

Most children in the care system are older, with the largest single group aged between 10 and 15.

Boys are slightly more likely to be in care than girls. According to official statistics, an increase in the number of boys has largely been driven by a rise in unaccompanied asylum seeking children, who are more likely to be male.

Although most children in care are white (75%), the slight over-representation of children from non-white backgrounds is also thought to reflect the rise in young asylum seekers.

7. There is a North-South divide...

There is something of a North-South divide when it comes to the number of children looked after by councils.

For instance, in Blackpool out of every 10,000 children there will be 184 in care.

That compares with 34 in every 10,000 in Windsor and Maidenhead, part of the Prime Minister Theresa May's Berkshire constituency.

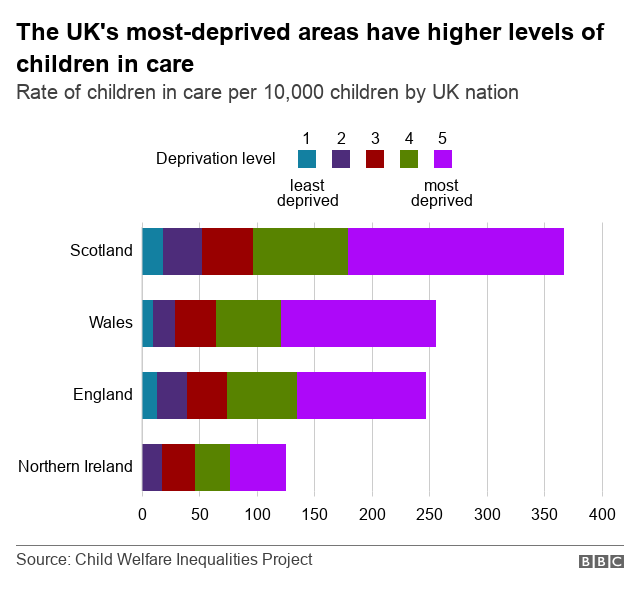

8. ...and there are divides within communities

Talk to social workers and many will say they are seeing families facing real financial hardship, with austerity and welfare cuts playing their part in pushing people into crisis.

That's reflected by research that found children living in the poorest areas were at least 10 times more likely to be taken into care than those in the most affluent parts of the country. It is a pattern that is repeated across all the nations of the UK.

The Child Welfare Inequalities project, external concluded deprivation was the largest single factor in families becoming involved in child protection.

In the most deprived areas about one child in every 60 was in care, compared with one in every 660 in the wealthiest areas.

With poorer areas spending more money on those in care, the team also concluded these authorities had seen more cuts to preventative services.

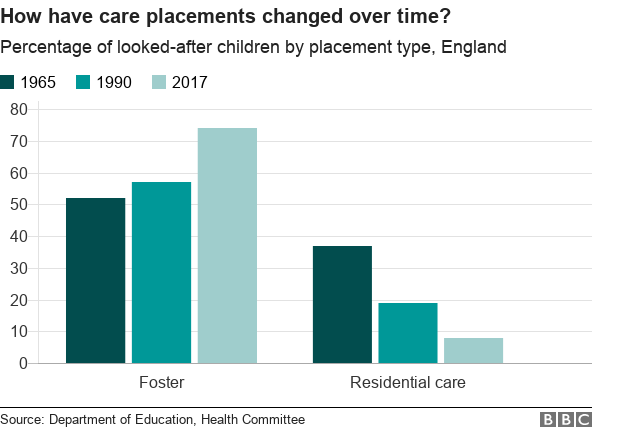

9. Most children are with foster parents...

Nearly three-quarters of children being looked after by councils live with foster parents, which costs local authorities about £1.7bn a year , external.

Since the 1960s, government policy has moved away from residential children's homes.

Foster carers play a vital role but there aren't enough of them. A review published in February 2018 said that the shortage depended on what part of the country a child was in and the availability of foster carers able to take on the most challenging young people.

Of the children who are not fostered, about 4,000 are placed with their own parents under supervision and nearly 8,000 spend time in children's homes, secure units or living semi-independently.

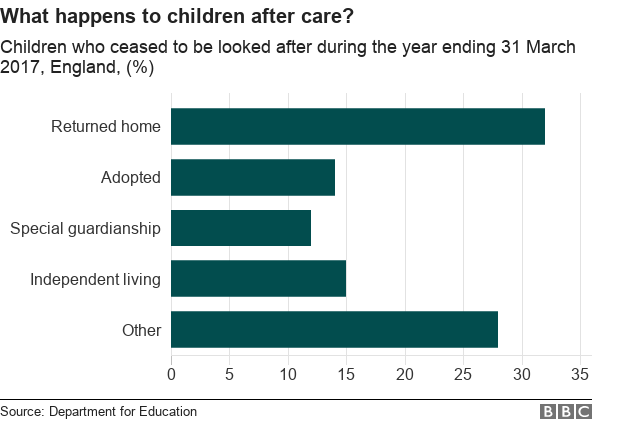

10. ...and children are likely to return to families

Almost a third of the more than 31,000 children who left care in 2017 returned to their families.

About 14% were adopted, after spending an average of two years in care.

For 12% of the children, there were special guardianship orders, where a relative took on their care. The number of adoptions has fallen since its peak in 2015, which followed a high profile push to increase numbers by the then Prime Minister, David Cameron.

Most of the children who were adopted in 2017 were aged between one and four years old. Only 1% of adopted children were aged 10 or over, even though this represents the largest age group of children being looked after by councils.

11. Children often face difficulties after care

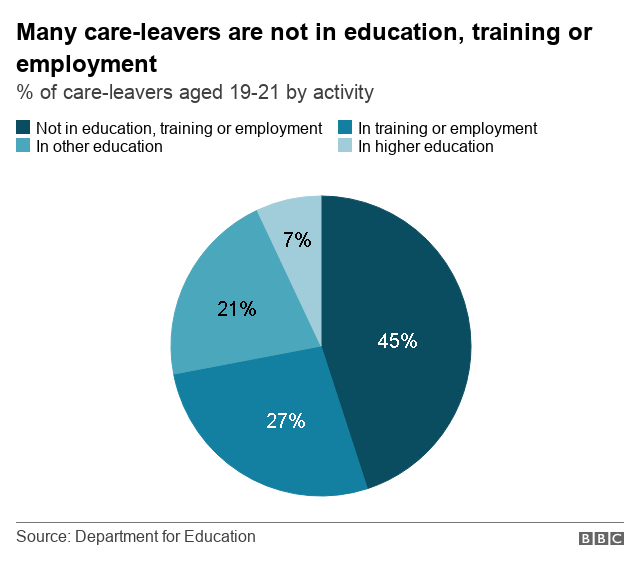

About a quarter of children who cease to be looked after when they reach their 18th birthdays continue to live with their foster parents but the future for many care leavers is difficult. Of the 18- to 21-year-olds who stayed in touch with councils, 40% were not in education, training or employment.

Although half of care leavers were in some form of education, training or employment, only 6% went to university. That compares with 33% of all 18-year-olds. It's also estimated that about a quarter of inmates in youth prisons have spent time in care.

Additional research by Ben Butcher and charts by Visual Journalism Unit.