Seven charts on the £73,000 cost of educating a child

- Published

The amount spent on schools is a major topic in this year's election campaign. So, where does all the money for educating the country's children go?

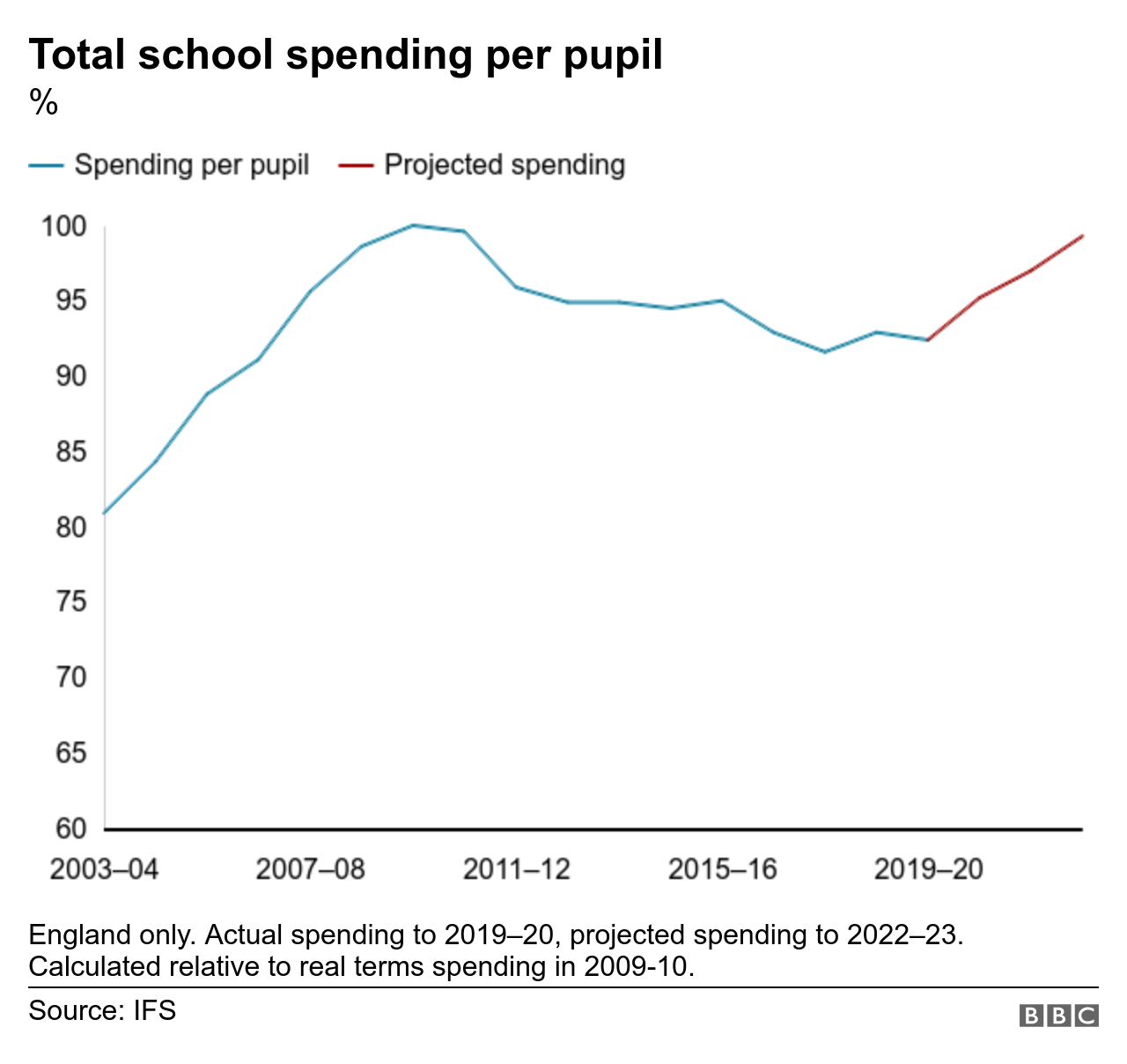

Spending on schools in England is much higher than it was 20 years ago. But that's not the full picture in a country which has seen a population boom coincide with a decade-long squeeze on public spending.

This means that in today's prices, spending per pupil in England is lower than it was in 2010.

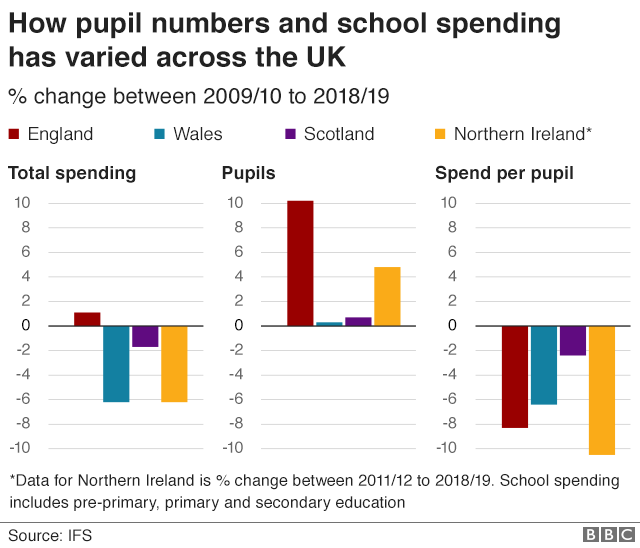

Education is a devolved issue. The amount the other nations spend on public services, including education, is linked to the amount spent in England via the Barnett Formula.

While school funding varies across Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, all parts of the UK have effectively seen a fall in spending per pupil since 2010.

Where the money goes

Spending on schools is not shared out equally. The amount spent on each primary school child in England in 2018-19 was £5,000, compared with £6,200 for secondary school children.

However, priorities have shifted, with per pupil spending on primary schools increasing by 145% since 1990 after accounting for inflation, compared with 83% for secondaries.

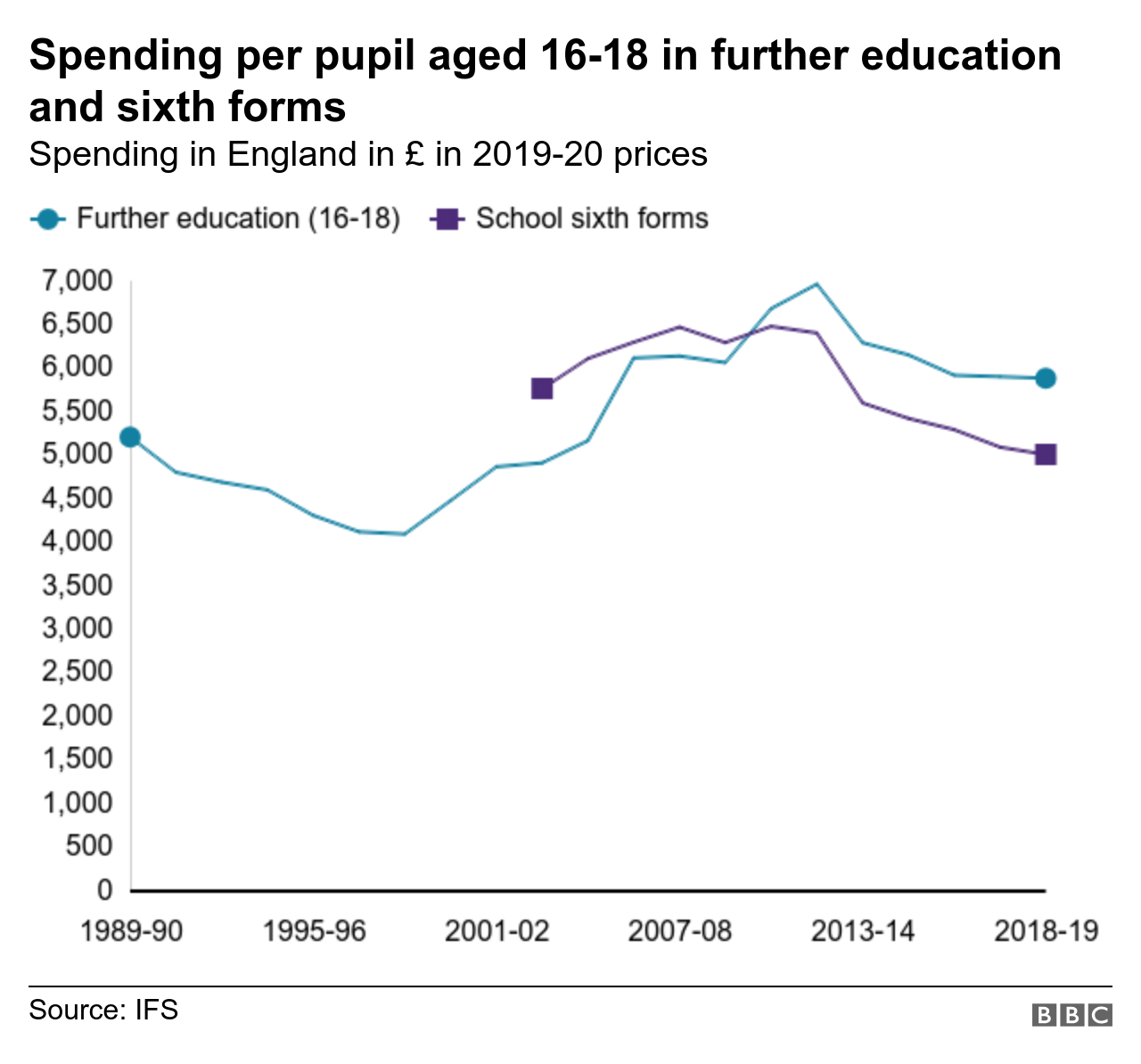

There has been less money for older children, with spending on further education students aged 16-18 up only 16% since the early 90s.

All of this money for nurseries, schools and colleges comes from the government, although most of it is spent via local authorities and other bodies.

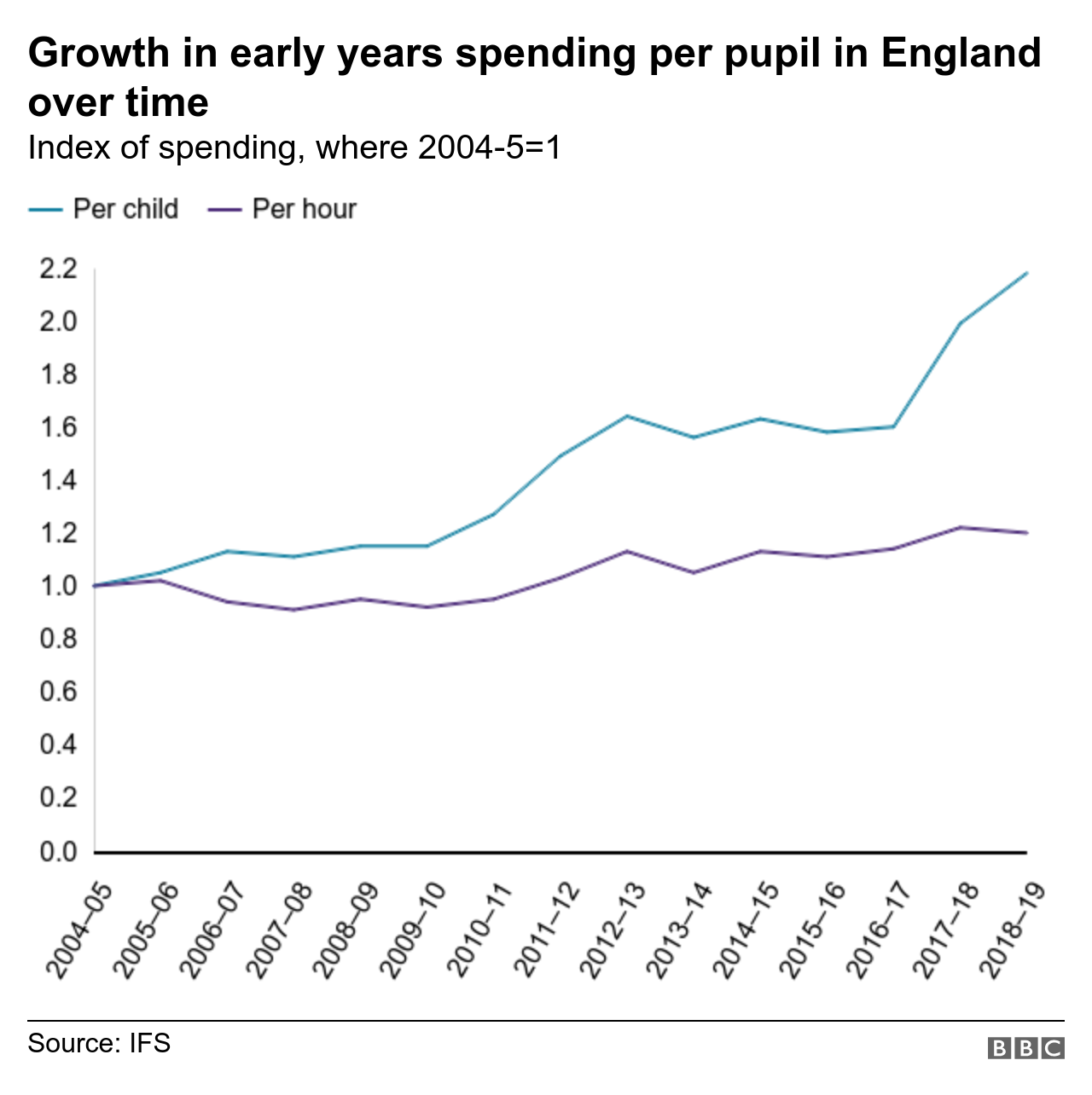

Spending on nursery age children has more than doubled

One of the biggest changes in education spending has been for very young children.

Parents of all three- and four-year-olds are now entitled to 15 hours a week free childcare, for 38 weeks a year.

And since 2017, all working parents in England have been allowed 30 hours a week, although there has been criticism of nurseries making up for funding shortfalls by adding "extras".

The expansion of free childcare has seen spending per child more than double between 2004 and 2018, from £1,600 to £3,800 in today's prices.

The population boom

Day-to-day spending on schools in England is set to be about £44bn in 2019-20 - roughly the same as in 2009-10, after inflation.

However, since then the number of schoolchildren has grown by 850,000 - the equivalent of a whole extra year group across the schools system. As a result, spending per pupil has fallen 8% in real terms since 2009-10.

An annual £4.3bn spending increase in England is planned by 2022 in today's money. This would roughly reverse the cuts of the last decade, but keep spending at the same level as 13 years earlier in 2009; a substantial squeeze on school resources compared with recent history.

Looking across the UK, real terms cuts in school spending per pupil have been largest in Northern Ireland (11%), where pupil numbers have also grown. Cuts have been smaller in Wales (6%) and Scotland (2%), where pupil numbers have been steady.

What are the parties promising on education?

Here's a concise guide to where the parties stand on key issues like education and schools and universities.

The squeezed teens

The number of young people continuing in full-time education after the age of 16 has more than doubled - from four out of 10 in the mid-1980s to eight out of 10 now.

However, the reduction in per pupil spending has been greater for this group than others, with sixth forms and further education colleges seeing the smallest increases over the past 30 years.

Among sixth formers, the amount available for each pupil has fallen 23% in real terms, from £6,500 a year in 2010 to £5,000 in 2017 - lower than at any point since at least 2002.

Funding per young person in further education colleges fell by about 12% between 2010 and 2018, to the lowest level since 2004.

About £300m extra has been pledged for colleges and sixth forms by 2020 in today's money, boosting spending by 4% per student.

CONFUSED? Our simple election guide, external

POLICY GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

BREXIT: Where do the parties stand?

Apprenticeship and tuition fees boost

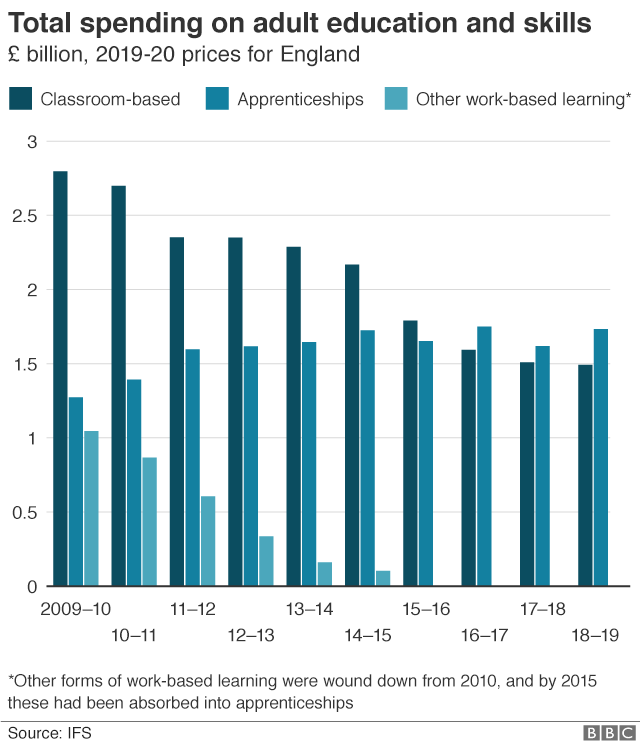

Total spending on adult education - not including apprenticeships - has fallen by half over the past decade and by nearly two-thirds since 2003.

This fall has been mainly driven by deliberate attempts to reduce the number of adults taking relatively small and low-level qualifications., external The recent Augar review of post-18 education has recommended reversing some of these cuts.

By contrast, apprenticeships spending has risen by 36% in real terms in the past decade. This was mainly driven by more adults aged 19 or over undertaking one, with the share of young apprentices unchanged at 5%.

Although controversial, tuition fees have led to an increase in funding at universities. For each full-time student, English universities are due to receive an average of about £9,300 in 2019-20.

This means per student funding is up 12% in real terms since 1990, despite the number of undergraduates doubling.

The government provides most of this funding for higher education up front, either in the form of grants to universities for teaching, or loans to students for tuition fees.

In the long run, the cost to government is lowered as student loans are repaid, with graduates paying more if they earn more. However, most graduates won't repay all of their student loans by the time they are cancelled after 30 years - amounting to a government subsidy for graduates.

What difference does spending make?

There have been big changes over the past 20 years.

Education spending has grown fastest for very young children, as studies indicate early intervention can pay off later on.

However, some argue the cuts made to 16- to 18-year-olds' funding may weaken the effects of this early investment.

Calculating the effects of such choices is not easy. The impact of decisions made now may only become clear years later, as children enter adult life.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Luke Sibieta is a research fellow, external at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent research institute that aims to inform public debate on economics.

More details about its work can be found here, external and on Twitter, external.