Primary school tables: Poor pupils won't catch up for 50 years

- Published

- comments

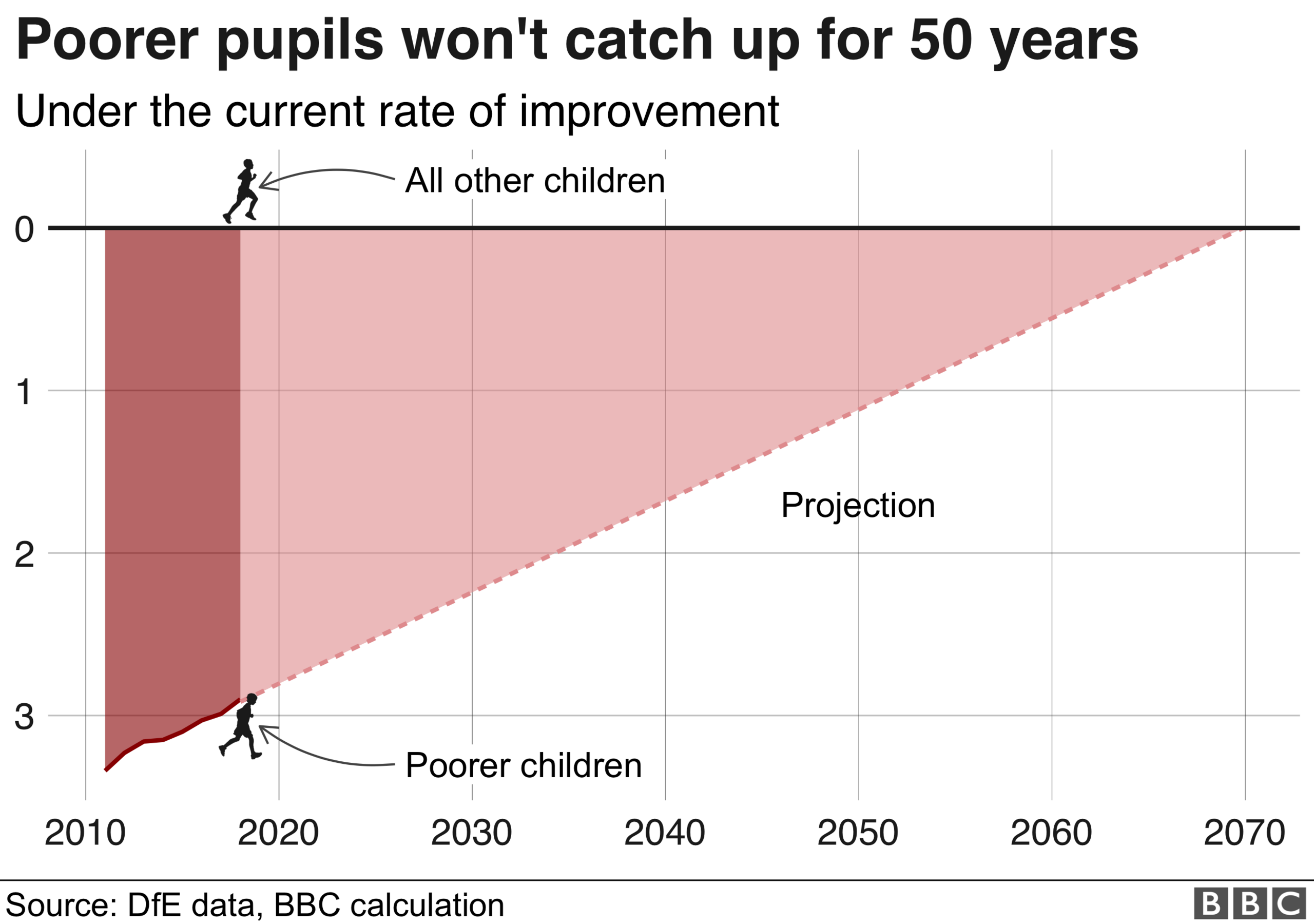

As new primary school data is released, BBC analysis suggests it will take 50 years to close the achievement gap between England's rich and poor pupils.

If the pace of change remains the same as it has done since 2011, poor pupils will not catch up until 2070, it shows.

This year, 51% of the poorest pupils reached the expected level in their national end-of-primary school tests.

This compares with 70% of their better-off peers, leaving a gap of 19 percentage points.

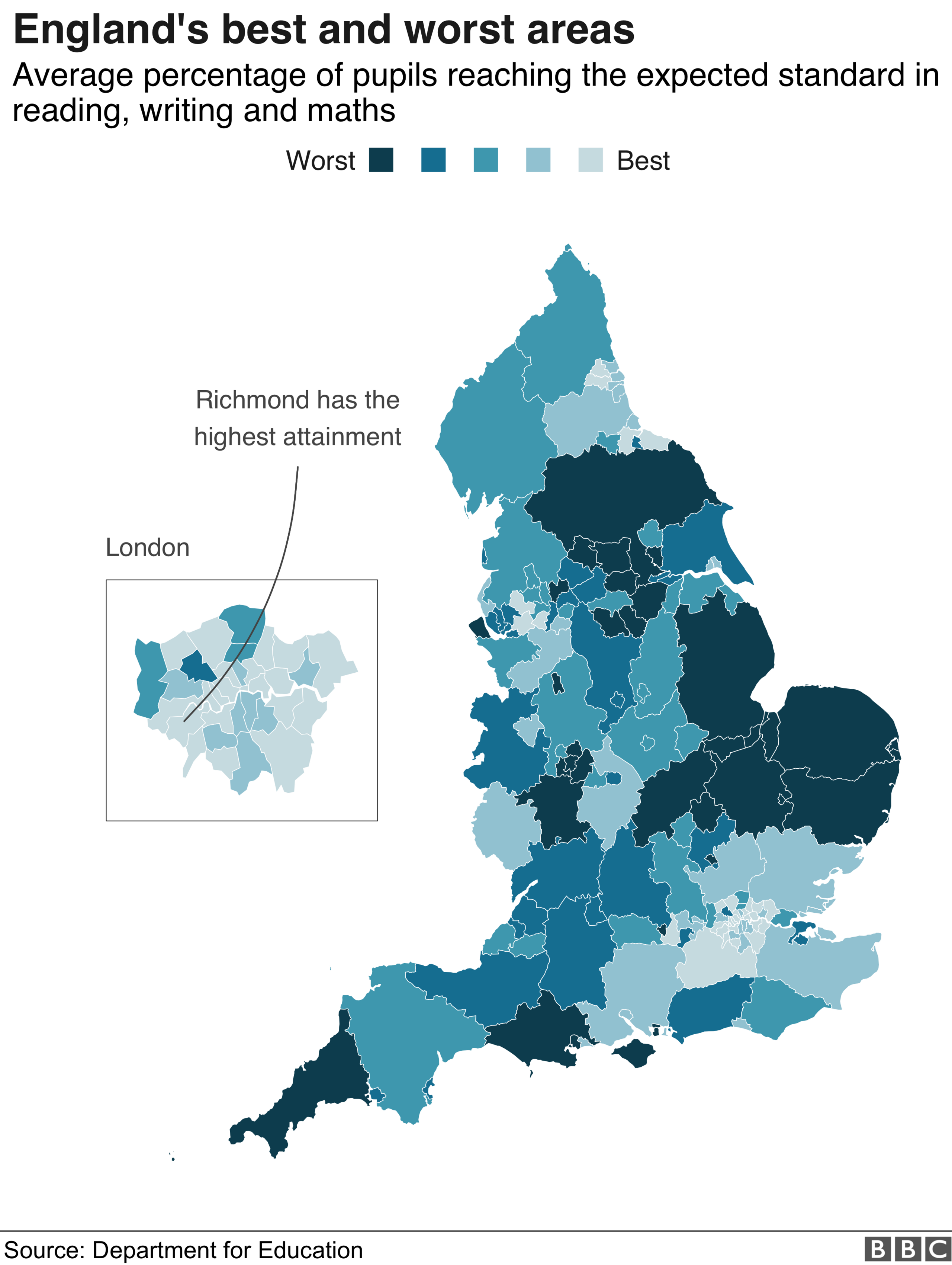

Readers can check how schools in their area have performed through the BBC's postcode search below.

If you can't see the postcode look up, click or tap here, external.

What's in the school league tables?

League tables are the shop window of every school, and parents often use them to help choose schools for their children.

They are based on the performance of pupils in each school in their end-of-primary national curriculum tests, known as Sats.

This year was the third time children sat the government's tougher tests, introduced in 2016.

The tables give a snapshot of how each school is performing in results and pupil progress but they also provide a huge amount of data on education at a national level.

The government has said the attainment of disadvantaged pupils is a key aim of its education policies.

The achievement gap has shrunk every year since 2011 but at a slow pace.

If this pace continues, the gap in attainment at this early age will not close until at least 2070, BBC analysis reveals.

To assess this gap, the government uses pupils' results in reading and maths tests.

These are ranked from best to worst as if they were the results of a race.

On average, poorer pupils rank worse. This difference in average ranking between poorer and better-off children is the disadvantage gap.

The current gap shows that poorer children would sit 2.9 places further back on average in a ranking of 20 poorer and 20 better-off children.

Explaining the disadvantage gap in primary school test results

School Standards Minister Nick Gibb said: "Standards are rising in our schools, with 86% of schools now rated good or outstanding as of August 2018, compared to 68% in 2010 and these statistics show that the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers has closed by 13% since 2011."

In 2011, the disadvantage gap was 3.3 places, it is now 2.9 places, having closed by 13% or 0.4 places.

Mr Gibb added: "Every child, regardless of their background, deserves a high quality education and opportunity to fulfil their potential."

The BBC's Education Editor Branwen Jeffreys explains primary league tables

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, said: "Schools make incredible efforts to guarantee that every child gets the best possible start in life.

"For their troubles, each year they find themselves propelled to the top or condemned to the bottom of a league table based solely on a few short tests of young children in a small number of subjects. This entirely wrong, so we shouldn't celebrate too loudly, or berate too strongly.

'Very vulnerable'

He added: "Successive governments have raised the stakes when it comes to Sats and league tables. Whilst the results have always carried a high level of importance, over time the pressure surrounding them has increased.

"One year's dodgy data can make an effective school leader suddenly feel very vulnerable. A system built on this sort of fear is not a healthy one."

Children are counted as disadvantaged if they are eligible for the pupil premium, that is if they have been eligible for free school meals at any point during the past six years or have been in care continuously for at least six months.

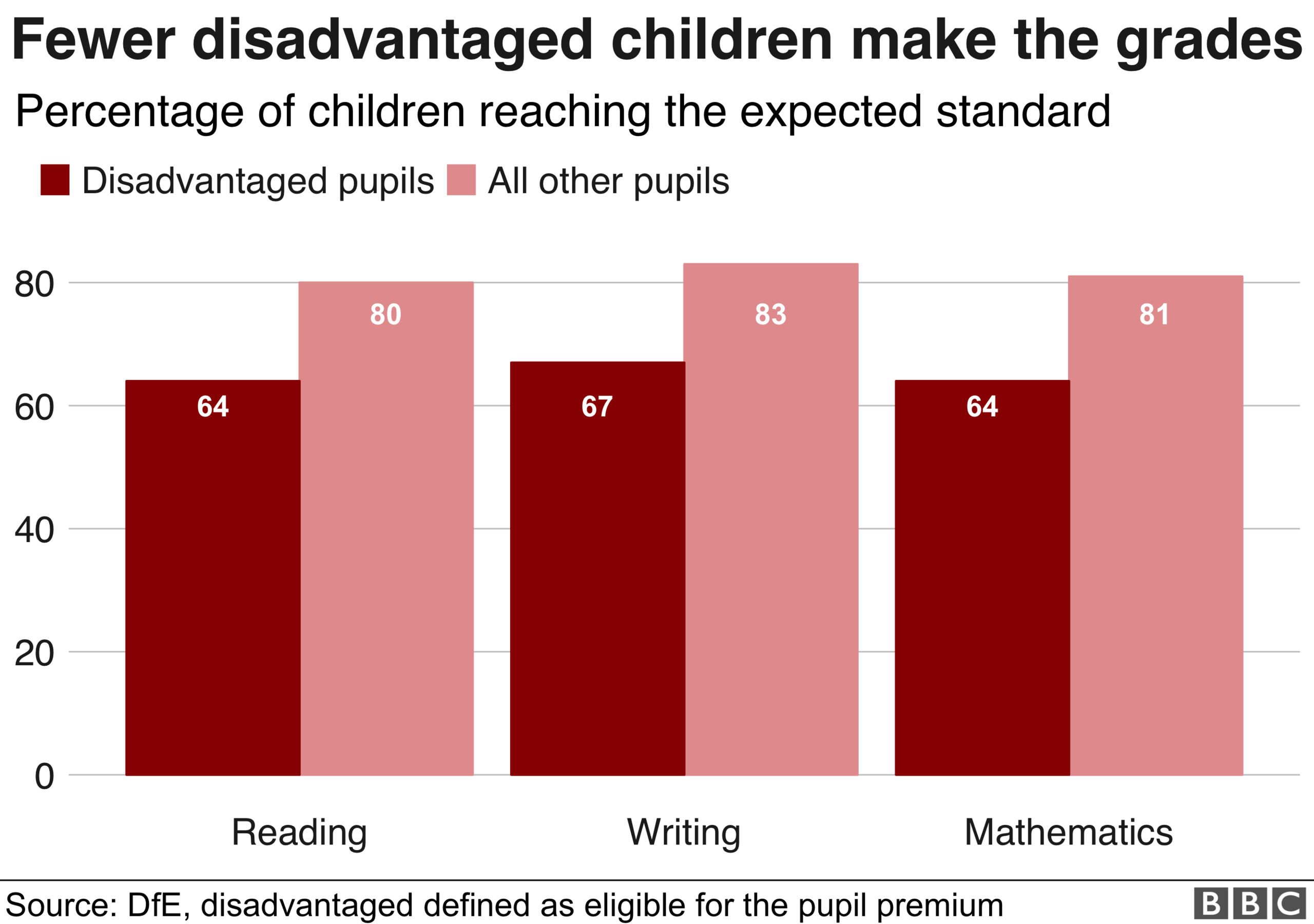

Data published in July revealed 64% of pupils met the expected standard across all tests: reading, writing and mathematics - up from 61% the previous year.

- Published12 December 2019

- Published10 July 2018