Student loan ruling adds £12bn to government borrowing

- Published

- comments

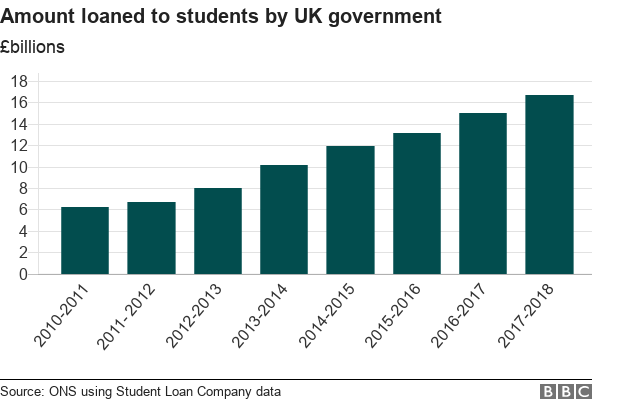

A change in how student loans are recorded in the public finances will add £12bn to the deficit, following an Office for National Statistics ruling.

The amount expected not to be repaid, which could be 45% of lending, will be reclassified as public spending.

Student loans will now significantly push up the UK's deficit - providing an incentive to reduce tuition fees.

The government said the change would be taken into account by the tuition fees review, due to report early next year.

The decision by the statistics agency tackles an anomaly in which the cost of lending to students, to cover fees and maintenance, has been missing from the public finances.

It will significantly increase the deficit - which is the difference between what the government spends and what it receives.

Nicky Morgan, chair of the Treasury select committee and former education secretary, welcomed the ruling - saying the current loans system lacked scrutiny when the government could "spend billions of pounds of public money without any negative impact on its deficit target".

The independent economics think-tank, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says the accounting system has been "absurdly generous" to the government's finances.

It says the effort to reflect the real cost of the fees system, in which 70% of students will not fully re-pay, would bring public finances closer to "economic reality".

The change applies across the UK, but most of this will be accounted for by lending to students in England.

Why does it matter?

It might sound like a technical change - but it has major implications for the level of tuition fees in England.

The decision by the ONS will provide a juicy carrot for the government to lower fees from £9,250 - because under the accounting changes, the higher the level of fees, the higher the lending and the greater the negative impact on the deficit.

If the government does nothing - and sticks with the current level of fees - the damage to the deficit will rise from £12bn at present to £17bn in five years, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Student finance is under review and if fees were lowered to £6,500 or £7,500, as has been suggested, it would mean less pressure, at least in presentational terms, on the public finances.

It would also leave universities worrying about how their budgets would be compensated.

But in terms of the political importance attached to reducing the deficit, tuition fees in their current form might suddenly look much less attractive.

The IFS says it is likely to mean the government will look for other options - which could mean lower fees, lower interest charges or fewer students.

The think tank also warns that it if the Chancellor had about £15bn in room to manoeuvre, much of that will have been wiped out.

What is being changed?

Almost half of the value of student lending is expected to be written off - and this will now be reclassified as spending, which the ONS says will push up the deficit by £12bn.

It will end an arrangement accused of being a "fiscal illusion" by the House of Lords economic affairs committee.

The Lords committee forecast that not counting the cost of loans until they were written off after 30 years would grow into a trillion pound black hole.

The Treasury select committee had also warned that in effect most of higher education funding had disappeared from public spending figures.

The decision by the ONS will stop "kicking the can down the road" on the cost of student finance.

The new classifications will divide student loan payments into "genuine government lending" for the portion expected to be repaid - while the portion not expected to be repaid, around 45%, will count as spending.

What's the response?

While students might look forward to lower fees, universities are warning against a potential loss of funding.

Much of university funding in England is through tuition fees - and if fees were cut there would be questions about replacing the shortfall.

"Ministers may now be tempted to cut university funding because it will look better for the deficit, but good policy shouldn't be dictated by accounting rules," said Tim Bradshaw, chief executive of the Russell Group of universities.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, said the "180-degree flip" on accounting will seem "embarrassing for policymakers".

But he warned it could mean less funding for students as they "suddenly look much more costly to current taxpayers".

Alistair Jarvis, chief executive of Universities UK, warned against "knee-jerk reactions" which could cut spending on students or limit student numbers.

Labour's shadow education secretary, Angela Rayner, said it proved the "student loans system is a fiscal illusion which flatters the government's record".

A government spokesman emphasised that in practical terms, this "does not affect students, who can still access loans to help with tuition fees and the cost of living and which they will only start repaying when they are earning above £25,000".

- Published7 September 2018

- Published16 December 2018

- Published22 November 2018